You never know quite what to expect from CubCrafters these days. The company started by the late Jim Richmond in 1980 grew conventionally enough at first, refurbishing the Piper Cub in its many forms and then seeking to improve the design with more modern materials and practices than could ever be envisioned by Piper during the Cub’s heyday.

You never know quite what to expect from CubCrafters these days. The company started by the late Jim Richmond in 1980 grew conventionally enough at first, refurbishing the Piper Cub in its many forms and then seeking to improve the design with more modern materials and practices than could ever be envisioned by Piper during the Cub’s heyday.

Today we have three distinct lines, starting at the most modern XCub series–featuring, either importantly or sacrilegiously, depending on your point of view, a nosewheel variant. Then you have the FX/EX Carbon Cubs in the middle, configurable up to a 2000-pound-gross fun machine with a choice of engines and props. At the lightest end is the LSA-legal Carbon Cub SS, arguably the machine that helped fuel CubCrafters’ growth over the last decade. All share one important distinction: a conventional aero engine. That changed this spring when CubCrafters introduced the Carbon Cub UL with Rotax’s latest hanging from the firewall: the turbocharged, 160-hp 916 iS. It was like seeing grandpa show up to Thanksgiving in a Def Leppard T-shirt.

There is precedent. During the early days of the J-3 Cub, Piper was exceptionally agnostic about engines, fitting various versions of Continental, Franklin and Lycoming four-cylinder engines as well as the Lenape three-cylinder radial. To see the modern Cub-style airplane with something other than an air-cooled engine on the nose—outside of the increasingly popular STOL drags, of course—is still something of a rarity. But back in the day, Piper was open to experimentation amid concerns about postwar supply-chain issues. (You think it’s a new thing?)

So why the Rotax today? In describing the impetus behind the UL, CubCrafters’ Brad Damm said, “We needed an airplane for international markets. You have to have an airplane that runs on autogas. Avgas is available here but in some places in the world it simply isn’t. We also wanted an airplane that fit into the UL category around the world.” While the U.S. has LSA, other aviation authorities have different requirements for “lightweight” aircraft. What is broadly referred to as the UL (or ultralight) category is not the same as our version. Most countries stick to the 600-kilogram weight limit (essentially the same as our 1320-pound limit for LSAs on wheels), though there are exceptions that go as high as 700 kg (1543 pounds). It’s true that other CubCrafters models fit into the LSA weight limits but what makes the new UL compelling for the company is the multi-fuel (avgas and 94-octane autogas) capability of the Rotax.

Shifting Gears

Fitting the 916 iS to the UL is a natural from the weight standpoint. With the engine weighing just under 200 pounds, it goes a long way to keeping the overall weight down. Depending on props, the Rotax would be 40–70 pounds lighter than with the CC340 engine. The cowling is 30% lighter, the landing gear is titanium and the firewall is also titanium. Up front, the E-Props four-blade prop weighs less than 9 pounds including hub and spinner. (The UL has been tested with a constant-speed prop, but that’s not legal, yet, for LSA in our country, so this period of flight test centers on fixed-pitch props.)

“Our goal is to have the UL, at 1320 pounds maximum gross weight, have enough useful load for a 200-pound pilot, 120-pound passenger, 20 gallons of fuel and 20 pounds of baggage,” says Damm. If you’ve done the math, that’s an empty weight of 860 pounds, which is 32 pounds lighter than the listed spec for the Carbon Cub SS. “We’ve also fitted lighter avionics,” says Brad. “And we think there are other ways we can further reduce the empty weight.” Standard tankage is 25 gallons (24 usable).

The Engine Installation

The Engine Installation

CubCrafters took on the job of fitting the 916 first with help from Rotax itself and then by applying its own considerable R&D skills. But one thing to note as you pore over the photos in this feature: While the UL has been flying for more than three months and much of it works as intended, there are likely to be changes from what’s on the prototype to what you’ll be able to buy. In part this is because of the prototyping process, where some expensive options—like the carbon fiber rods that hold certain components—might not survive to production. Moreover, there are likely to be many changes to the basic configuration under the cowling—there are likely to be more as CubCrafters works to put the pieces in production. The company is investing in many new tools, including some production automation, so anything that goes into the UL has to be aligned with the overall business.

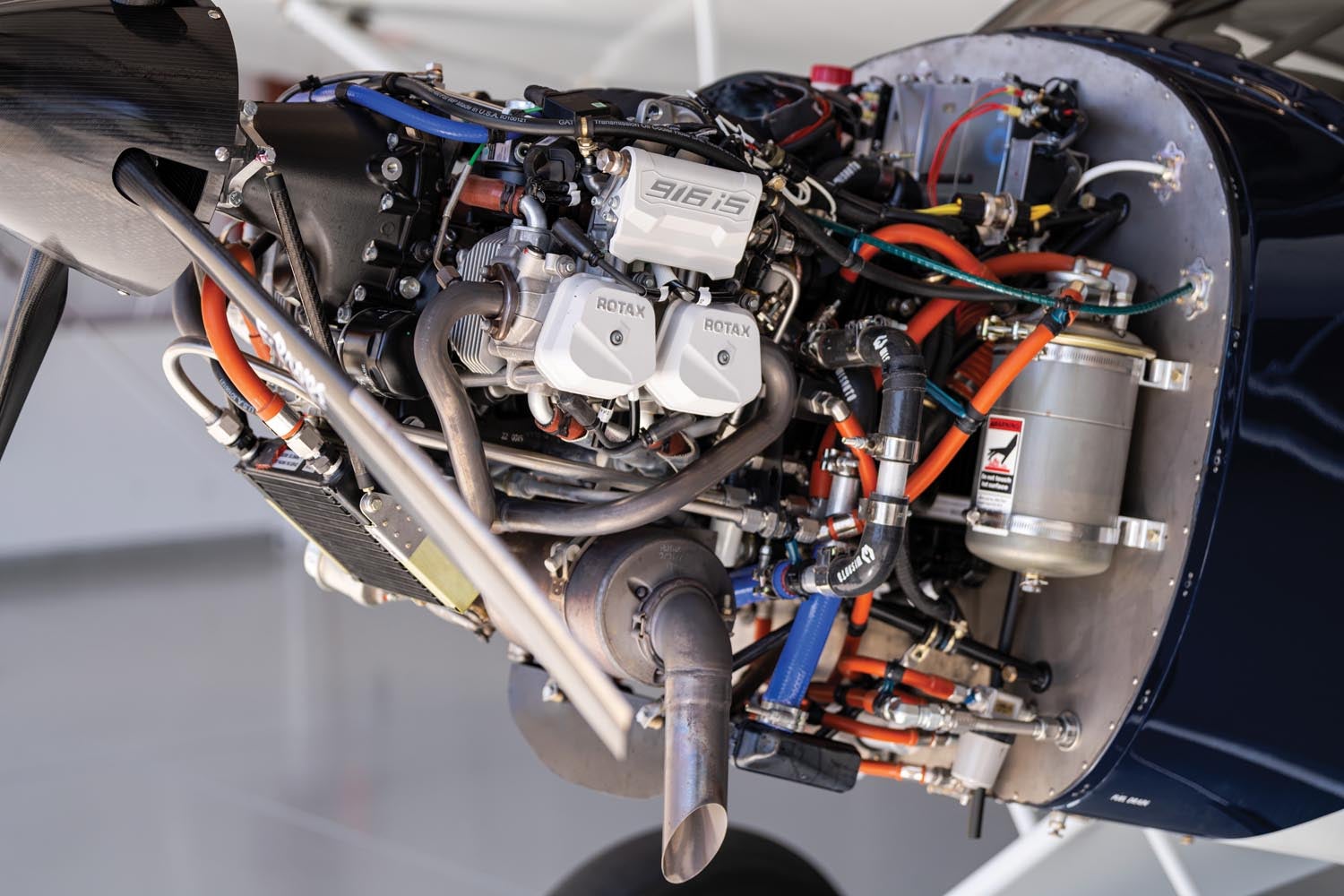

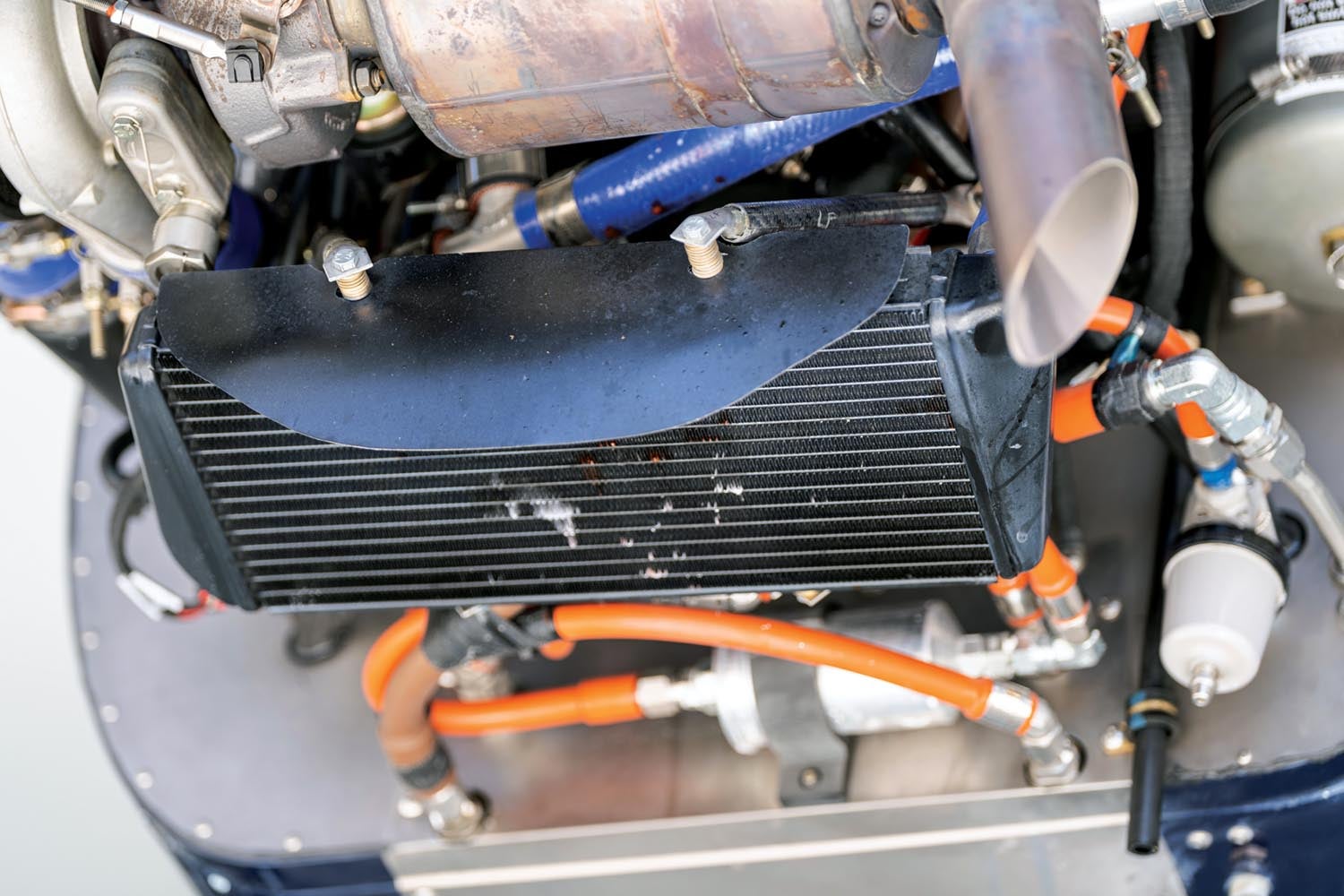

All that said, the 916 is a remarkably good fit on the front of the UL. It uses a conventional ring-style Rotax engine mount with extensions that pick up the firewall points common to the other engines used in the Carbon Cub SS series. The prop flange on top of the 916’s gear-reduction drive sits where it would with a Lycoming. Aside from the upper cowling using prepreg glass for weight reduction, the cowling overall is close to SS spec. The air inlets are rearranged, though. Under the spinner, the opening that normally feeds the airbox or carburetor ducts air to the oil cooler. In the copilot-side cheek, a splitter pulls incoming air back and toward the standard intercooler. Air entering the other side of the split and the pilot-side opening are led back to a pair of coolant radiators. A duct integrated with the top of the cowling helps feed a tall radiator just behind the engine while another is positioned along the lower surface of the cowling in the exit-air path.

This arrangement is very likely to change. My flight in the airplane, on a not particularly warm day, began to stress the coolant temperatures, something CubCrafters has seen in its testing and is working to remedy as R&D continues. They haven’t said what the exact next steps will be, but a betting person would plunk down on improving the cooling-air flow before trying bigger, heavier radiators. It’s possible a general reshuffling of the back end of the engine might allow one larger radiator, but that’s a project for the near future.

The rest of the packaging is very tidy. Rotax supplies the turbocharger and exhaust system, which includes a pneumatically operated, electronically controlled wastegate. In the UL, induction air comes in via a large conical filter at the turbo inlet. Its location inside the cowling should stave off concerns of induction icing. As with all 900-series engines, there’s a remote oil tank on the pilot’s side of the firewall, meaning you get the joy of “burping” the system before flight to accurately check the oil level. Quick warning here: The E-Props blades are really sharp on the trailing edges—bring gloves.

On the firewall is the Rotax-supplied power-distribution system that manages the dual ECUs that, in turn, control fuel injection, ignition and wastegate functions. As with the 915, the 916 iS has a motorcycle-style generator on the back end of the crankshaft, though it has independent circuits. From certain angles, the installation looks really complex and fairly tight but the important maintenance items are readily accessible. You drain oil from the remote tank and the oil filter lives on the front of the engine near the prop drive. All eight auto-style spark plugs are easily accessible, too. TBO is 2000 hours, up from the 915’s 1200.

One area CubCrafters hasn’t nailed down is cabin heat. Many Rotax installations use small heat exchangers fed by the cooling system for cabin heat but there’s a good chance some way to recapture exhaust heat will be needed for the expected backcountry use of the UL.

Flying the Thing

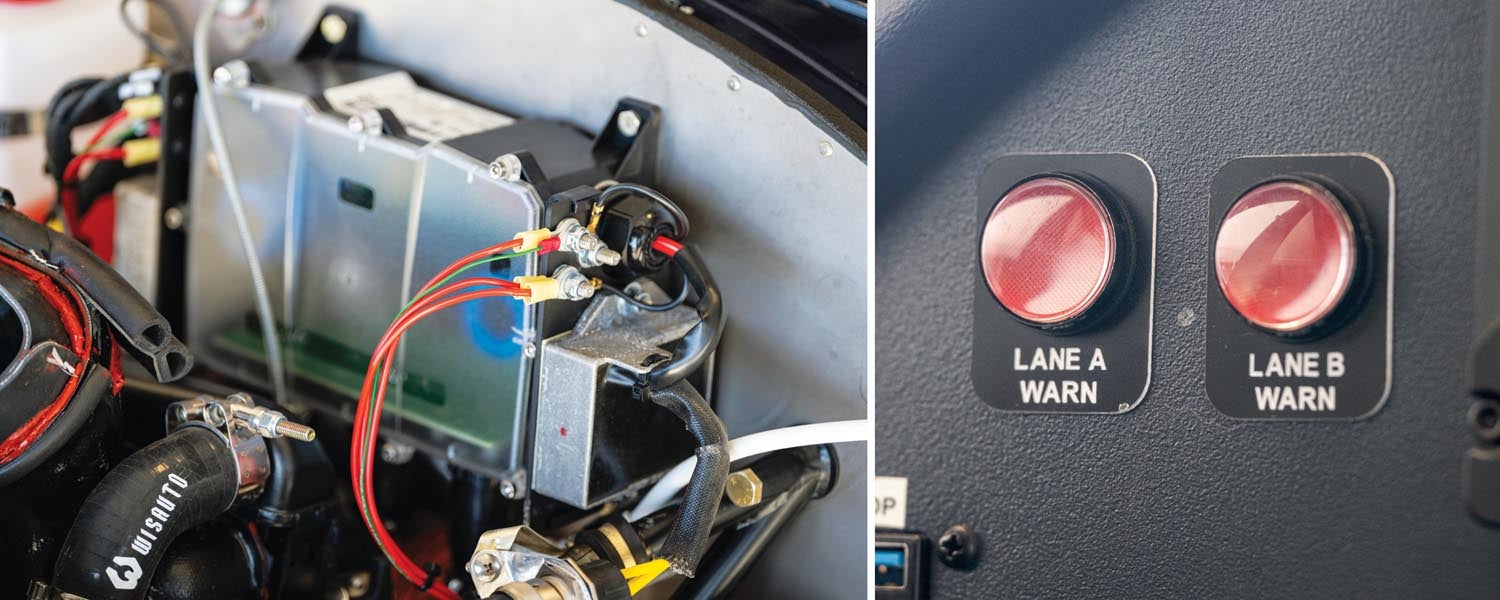

Pilots who are familiar with the Rotax 900-series engine and, in particular, the turbocharged 915 iS or non-turbo 912 iS will be immediately comfortable in the Carbon Cub UL. The UL prototype uses the smaller SS-style instrument panel that, in this case, carries a smaller 7-inch Garmin G3X Touch main display with an RS Flight Systems EMU (engine monitoring unit) display just to the left. It reveals crucial engine information like manifold pressure, rpm, oil pressure and temp, coolant temp, fuel pressure and flow, total fuel quantity and system voltage. It also shows throttle “percentage” and the status of Lanes A and B.

In the parlance of Rotax’s dual-channel ECU, “lane” refers to each leg of the parallel computing system. The engine can run on either but typically has Lane A running the show with Lane B humming along in the background, a faithful understudy ready to step in should the lead actor stumble off the stage. (By accident, of course.) You’re aware of the ECU status on both the EMU display and through two big annunciators that warn of a fault with either lane.

Over on the far right is a seven-position key switch that greatly simplifies checking the lanes and the dual electric fuel pumps. Once the engine is started—it lights off just like a Rotax, a brief clatter from the gearbox then a smooth, steady idle—you’ll need to bring the engine speed to 2500 rpm to complete the generator check. In Rotax’s world, one generator is dedicated to running the engine systems (ECUs, ignition, injection and fuel pumps) while the other powers the rest of the airplane and charges the main battery. Should the first generator or its regulator fail, the system automatically falls over to the second generator/regulator combo, but that leaves not a lot of extra for lights and avionics, so load shedding is advised.

With the engine at 2000 rpm, the system check is like this: Switch to position A, which runs Lane A and the main fuel pump. Wait 15 seconds to allow the self-check to run. Pause a second in the A-B setting, then to position B, which runs Lane B and the auxiliary fuel pump. Once both Lane A and Lane B warning lights extinguish, you’re good to go. But before heading off, it’s worth understanding that the Throttle readout on the EMU is slightly misleading. You take off at 100%, of course, but maximum-continuous cruise is 98%, which requires you to pull the physical throttle back almost halfway.

On the Runway

The last CubCrafters I flew was the EX-2 with 180 hp and the fixed-pitch prop—the one before that was the NXCub with 210 hp on board. Even though I had in mind that the 916 has “just” 160 hp and that the UL, like the SS, is lighter than the EX/FX or XCub models, I hadn’t fully resolved the math. Lined up on the runway, you can slide the throttle forward smoothly but quickly. From there, the Rotax leans into the job with real vigor and no apparent throttle lag or turbo surge.

For its part, the Carbon Cub accelerates to flying speed with the customary one notch of flaps in less than 4 seconds and just seems to levitate. Once rotated, and if you have no need to clear terrain, you can let the nose settle not far above the horizon and enjoy the view of the runway falling away from you. In no way did the UL feel like it was 20 hp down on the last EX-2 that I flew. Impressive stuff.

In deference to the early stage of the UL’s cooling system, we pulled back to 95% Throttle and dropped the nose to attain 78 knots indicated (90 mph) and 500 fpm in the climb, where the coolant stabilized at 231° F and the oil temp at 190°. At this setting, the engine is pulling 37 inches of manifold pressure at 4800 engine rpm.

Later in the flight, we tested a full-power Vy climb (61 KIAS, 70 mph) where we recorded 1100 fpm. Fuel flow is 10.3 gph at 100% Throttle. At Vx, the airplane is substantially nose up to 46 KIAS (53 mph) and still climbing better than 800 fpm. We followed that with a quick high-speed cruise check. What’s impressive is how the nose drops with power. At 98% Throttle, the 916 is happily churning away at 42 inches and 5400 rpm, burning 9.9 gph. At 4900 feet msl, we saw 115 KTAS (132 mph true). I didn’t attempt to check the calibration of the pitot-static system for a couple of reasons. First, we were at a non-ideal altitude for the turbo Rotax, which can produce maximum power to 15,000 feet and maximum-cruise power to 23,000 feet. Second, several aspects of the CarbonCub UL’s cooling system will change between now and when you can buy one, so high-cruise data is more likely to change than not.

Let’s Be Reasonable

Unless you’re trying to outrun weather or sneak into your favorite backcountry strip before dark, there aren’t so many reasons to run high cruise in the UL. A more realistic cruise speed would be 95% Throttle and 6.4 gph, giving 104 KTAS (120 mph true). Even more economical are the results at 94% Throttle, where the UL trots along at 89 KTAS (102 mph true) on 4.9 gph; to get that, the Rotax is pulling 32 inches at 4700 rpm. Notable in this case is the engine’s smoothness and complete predictability with power changes. It moves from one thrust level to the next seamlessly.

After following rivers and observing wild horses from low level, Brad and I went to a local farmer’s field, conveniently located on a good-sized hill, for a few takeoffs and landings. The CarbonCub UL managed my ham-footedness with some forgiveness. Because it’s light and still has a ton of wing—179 square feet of modified USA 35(B) airfoil for just 1320 pounds—the UL loves to fly slowly and will come off the ground really quickly. In the landings where I was working hard to judge the sink rate as the steeply sloped runway came at me, I never thought about the engine or the drag profile. There’s always enough power and always enough control authority to get the job done. And I never thought about the engine out front—what I asked for, it did. My single handling complaint is that I miss the lighter G-series flight controls on the EX, FX, X and NX models. (The UL keeps the SS’s system simply because it’s lighter.)

Eventually, Brad and I switched seats so he could show me a few of the UL’s party tricks, including canyon turns that seem to have it climbing and reversing course in not much more than its own wingspan. Precision touchdowns where it feels like you can stop in your own length. STOL-worthy departures where there’s nothing but blue sky in the windscreen. All with two full-sized ’murrican guys and full tanks on a starting-to-get-warm early summer day.

Closing Thoughts

CubCrafters feels strongly that the UL has worldwide potential. Since starting the program with Rotax two years ago, it launched the airplane this spring at Sun ’n Fun and will continue development on the engineering prototype I flew. It’ll get flown with different props and other refinements through 2023. Early in 2024, the company expects to have half a dozen built for market survey purposes. That’s not likely to be the final design, either. “We like to get customers into the airplane, to see what they like and don’t like,” says Brad Damm, “And then we can iterate the design from there.” The design should get locked in mid-2024, with the manufacturing team refining its part of the process through the end of the year. Prices have not been set but will probably be closer to the $312K of the EX-3/FX-3 series than the current $237K of the Carbon Cub SS.

First customer airplanes are expected to deliver in early 2025. By then, the relationship between CubCrafters and Rotax will be more than four years along. Near the end of my visit, I asked Brad what company founder Jim Richmond would make of the UL. My limited time with Richmond revealed a forward-thinking but still very grounded man with a huge practical streak and more than a little appreciation for traditional design. Without hesitation, Brad said, “Jim knew we were working on the UL and I’m sure, if he had a chance to fly it, he’d love it.”

Photos: Jon Bliss.

“From certain angles, the installation looks really complex and fairly tight…”

From what angle doesn’t it look so?