Since this is our annual buyer’s guide issue, we thought it might be interesting to check in with a selection of our regulars to see what influenced their decision on what (and even when) to build. After all, the decision-making process is a complicated one—and very individual.

Since this is our annual buyer’s guide issue, we thought it might be interesting to check in with a selection of our regulars to see what influenced their decision on what (and even when) to build. After all, the decision-making process is a complicated one—and very individual.

Jon Croke: The ELSA Option

Sometimes the decision to build transforms into a decision to buy instead. Choosing to purchase a secondhand, ready-to-fly Experimental airplane has some attractive benefits. Someone else has done all of the time-consuming construction work. You can inspect the workmanship or have someone else help you with that. If all goes well, that aircraft may be ready to fly away at a potentially great price. It is common for original builders to put their aircraft up for sale due to health, financial or myriad other legitimate reasons. What is there not to like about these transactions?

For me, the big downside is that the new owner will not have the ability to perform annual condition inspections on this aircraft. Only a licensed A&P mechanic and maybe the original builder (if they obtained the credentials for their aircraft) can sign off the inspection each year. This can become a bit of a challenge sometimes as not every A&P is willing to perform this service on an Experimental aircraft.

Here is the good news—there is a little-known loophole (kind of) to this rule that you should keep in mind when shopping for previously owned aircraft. When the Light Sport Aircraft rule was created in 2005, it put pressure on the large pool of so-called “fat” ultralights to stop abusing the Part 103 ultralight FARs. In other words, stop flying—or else! These ultralights were by no means legal but were tolerated by the FAA prior to Sport Pilot and Light Sport rules. These aircraft included two-seaters, those that were way over the legal limit of 254 pounds and many even had Rotax 912 and similar sized engines. There were many light aircraft models in this collection you would recognize. (Some were really heavy, not even close to the legal ultralight limit!) If these aircraft were built today, they would have to be registered as Experimental/Amateur-Built and assigned an N-number. So, what happened to those fat ultralights? Where did they go?

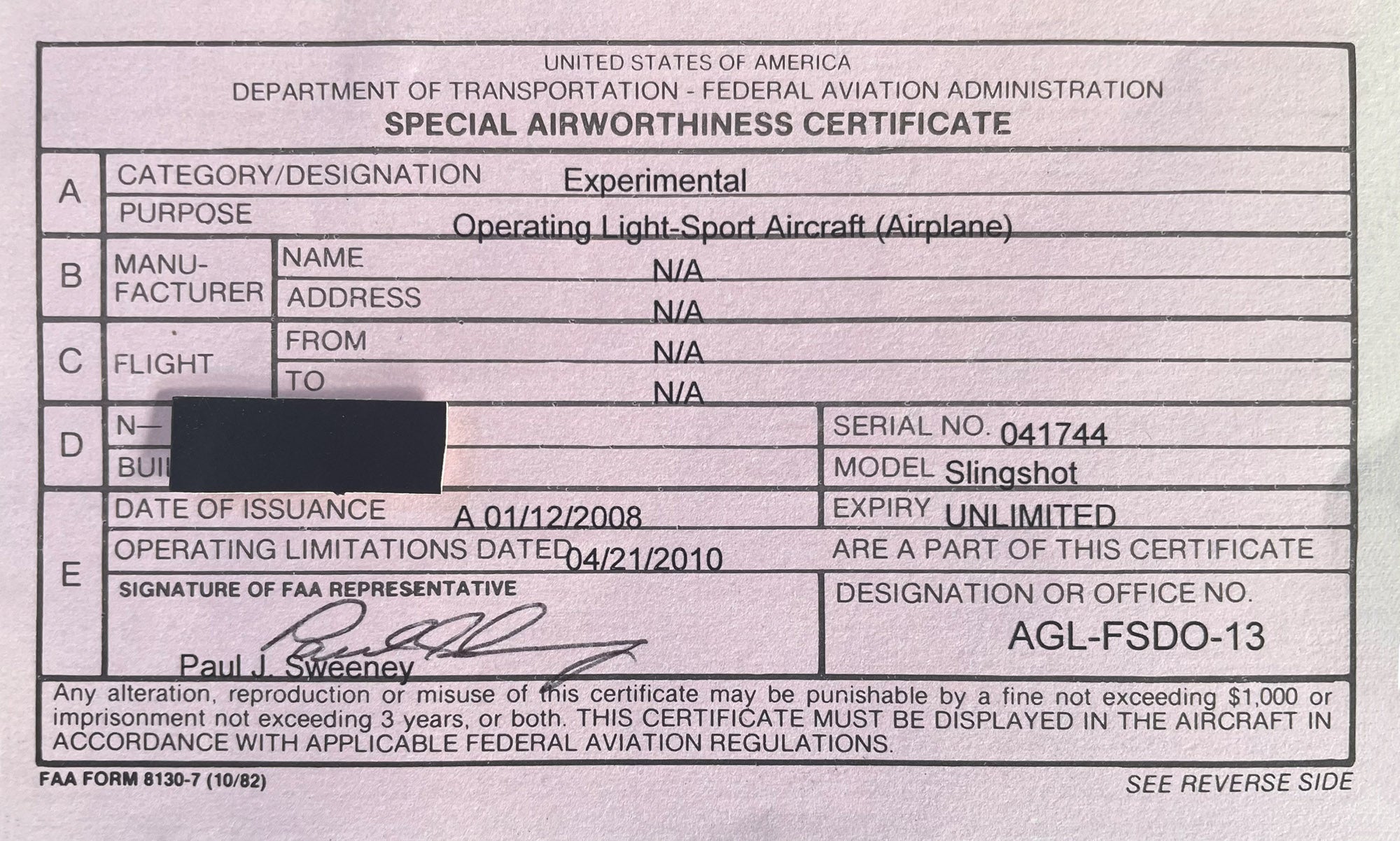

Soon after Sport Pilot was enacted, the FAA offered a real gift to those paying attention. An owner of an illegal ultralight was allowed to convert it to an aircraft with an N-number. After an inspection, the FAA certified the plane as an Experimental Light Sport Aircraft, also known as ELSA. A special airworthiness certificate, op-limitations and N-number were all issued. It was a crazy simple way to turn an illegal, unregistered, fat ultralight into a legitimate airplane. This program by the FAA ended back in 2008 (it was extended for a couple years after). Today, you can no longer perform these conversions. If you build a new aircraft, it is typically certificated as an Experimental/Amateur-Built. You cannot register it as an Experimental/Light Sport unless the kit factory has designed a special model that allows this. There are very few of these but the RV-12 is an example.

So, what is the benefit if you purchase a used aircraft that is certificated as an ELSA? The “loophole” I previously mentioned is simply that the requirement for condition inspections on an ELSA includes a person who has a Light Sport Repairman inspection rating certificate.

How does that help you? To obtain a Light Sport Repairman certificate with inspection rating you need to attend a 16-hour (two-day) class! If you can take the time to get this training and certificate—you now can perform condition inspections on an ELSA that you own. Wow! No need to look for and pay an A&P to do this each year. You can also make modifications to your aircraft, similar to the Experimental/Amateur-Built category.

The moral to this story is that if you consider maintenance and signing off inspections as a crucial part of aircraft ownership, then be sure to look for ELSA models when shopping the pre-owned aircraft marketplace. Sellers of these should be proudly advertising that their aircraft is certificated as ELSA. I recently purchased a Kolb Slingshot with a Rotax 912 that was converted to ELSA by an owner who took advantage of the conversion program. I am now heading for my two-day Light Sport Repairman course so I can enjoy the full privilege of signing the logbook for inspections.

Larry Anglisano: The Accidental RV-12

My decision to get involved with an RV-12 build—and ultimately shared ownership—was easy. I had flown one of the first factory-built RV-12 SLSA models for a report in 2014 with Van’s Aircraft’s Chris Thelan and a couple more times for other reports. What struck me about the airplane was that it had few if any bad habits. Handling was signature Van’s, which is crisp and responsive, and while the cabin is stark compared to other airplanes, I’m all for utility over luxury.

Moreover, I liked the smooth-running and fuel-efficient Rotax engine that seemed to be the right match for the airframe. I had flown both Dynon- and Garmin-equipped models and both made an already decent little LSA even better. For airplane owners on a budget, I felt the RV-12 ranked near the top, packing a big punch for the money.

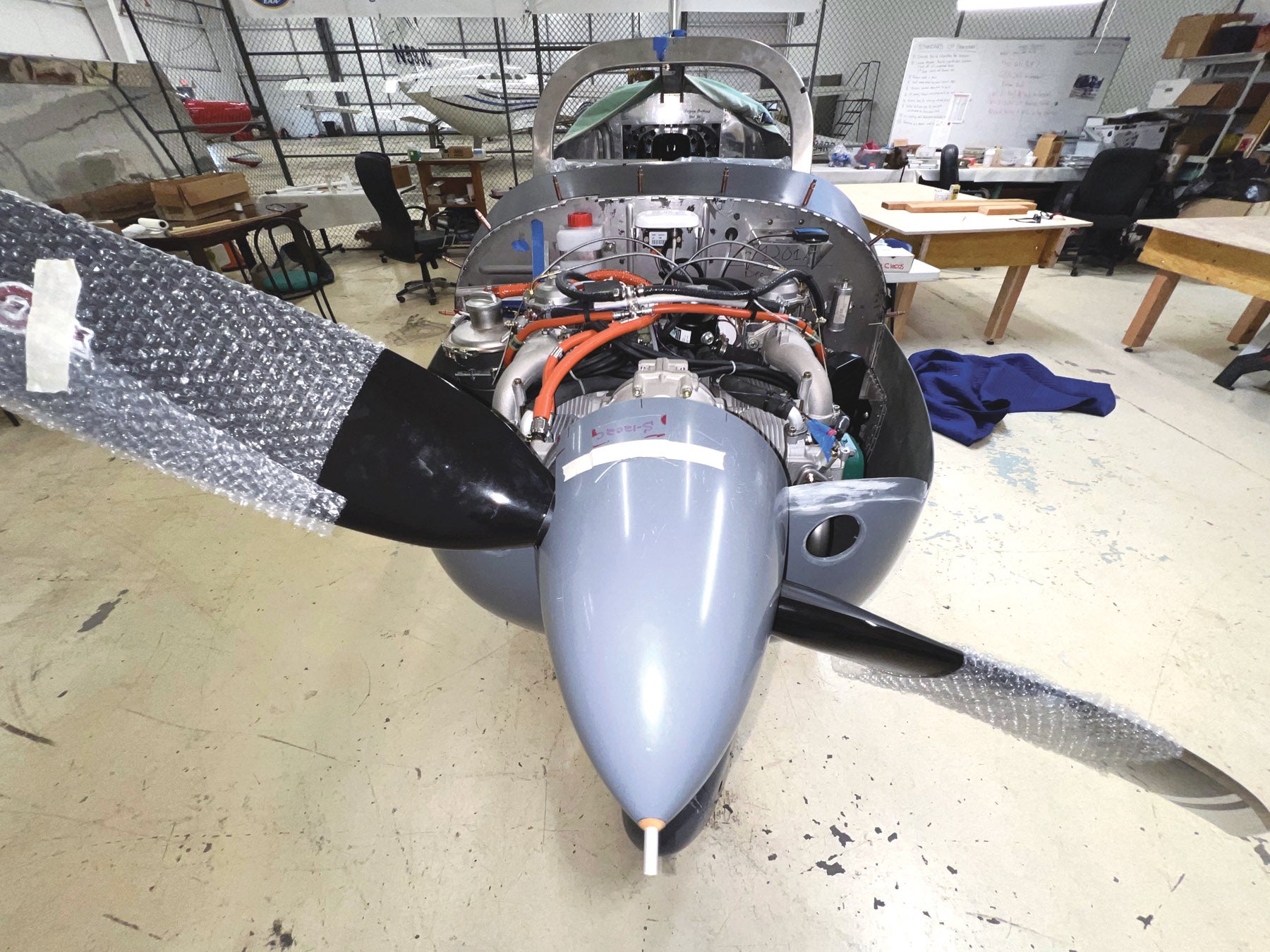

Flash forward to around 2020 when my local EAA chapter had a chance at acquiring an RV-12 kit. A local technical high school with a new aviation program purchased the kit several years prior with the intention of completing it, but changes in administration meant the airplane had to go. The wings were completed and some of the tail was put together, but this was a big project that was perfect for a chapter. The kit had a new in-the-crate carbureted Rotax 912 ULS—no fuel injection. The avionics weren’t purchased yet. When the school’s administration realized it would be taking on liability selling an Experimental airplane kit, it ended up donating the airplane to the chapter.

It’s time to build an airplane.

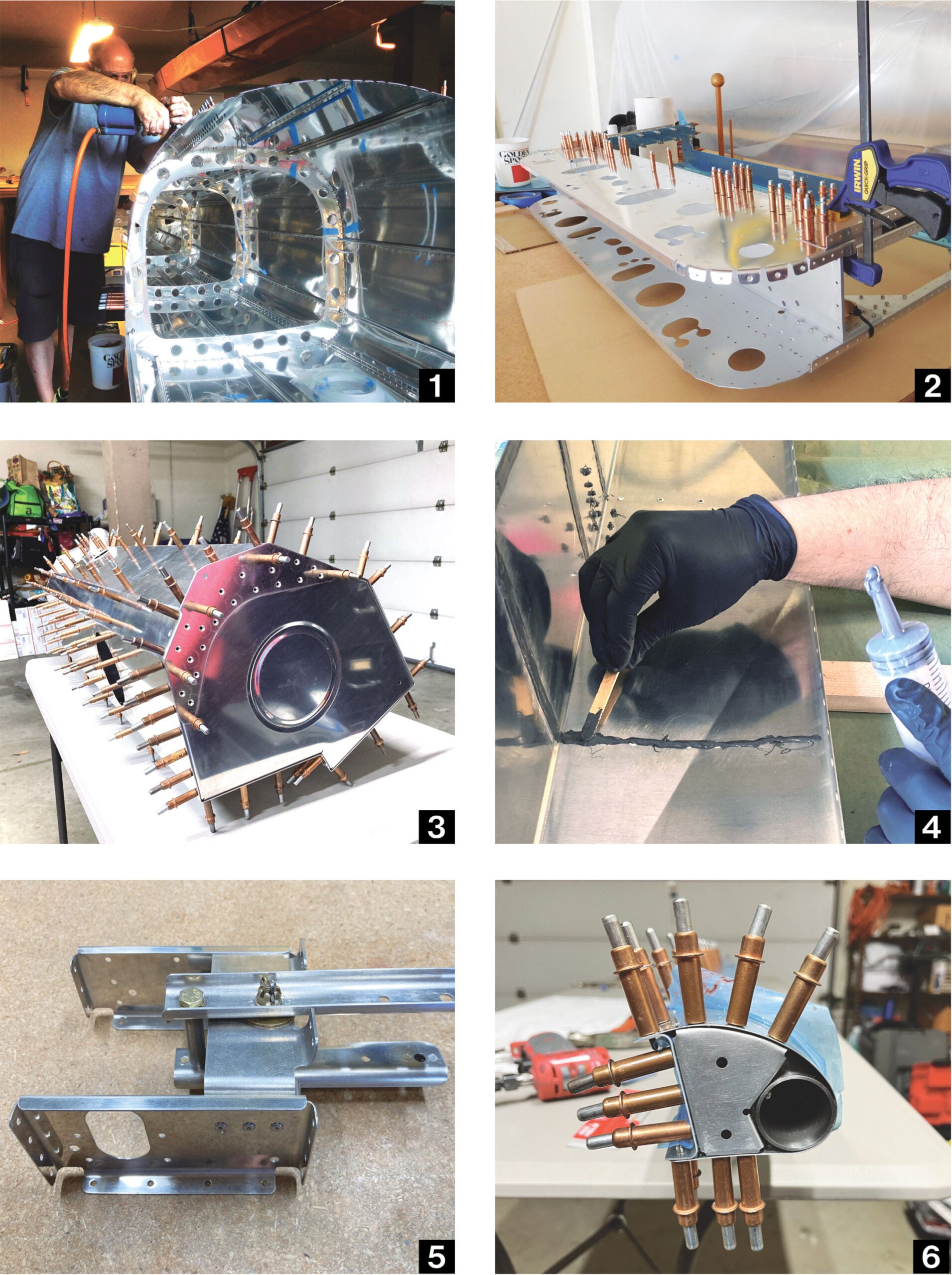

While my skills as a career avionics tech would come in handy when it was time to do the avionics, I’m not a metal worker and certainly not the guy to be setting the thousands of rivets that hold this little airplane together. Luckily the pulled-rivet construction of the RV-12 means there’s very little conventional riveting needed. Plus, there are plenty of skilled and accomplished builders in the chapter who are good with metal, and they (and plenty of volunteers) get big kudos for completing the bulk of the work.

With three-quarters of the aircraft assembled, a few of us decided that the RV-12 was such a decent choice that it made sense to purchase it from the EAA chapter (chapters can’t legally own and operate an airplane anyway) and create a small flying club. Sharing the costs of an already budget-friendly airplane fit our finances perfectly. We decided on the Garmin G3X Touch avionics and we each contributed to its cost as our buy-in, while later officially purchasing the aircraft. The engine is on, the avionics have been powered and configured and we hope to fly it by spring 2025.

So far, I think the RV-12 will serve my mission well, which includes local flying for work and fun. Plus, supporting a Van’s RV that we can call our own sure beats forking over a lot of rental dollars for aging FBO airplanes.

Mark Schrimmer: Another RV-12 Builder Speaks Out

I was in my mid-60s when I started looking for my current homebuilt project. Because of my age, I wanted a plane that met Light Sport Aircraft requirements and could be flown using a valid U.S. driver’s license as a medical certificate.

Having owned a Piper Warrior for many years, I prefer low wings. I also wanted side-by-side seating, tricycle gear, all-metal construction and a cruise speed as close as possible to the LSA maximum of 120 knots. After visiting various kit manufacturers at AirVenture, one plane stood out: Van’s Aircraft’s RV-12iS. Its delightful flight characteristics and innovative features made it the right choice for me.

In the RV-12iS, the pilot and passenger sit ahead of the main wing spar near the wing’s leading edge. Not only do you get a great view looking up through the large bubble canopy, there’s good visibility looking down!

I was intrigued that the wings were designed to be quickly and easily removable. Since I live in an area where hangars are in short supply and waiting lists are long, I could see where this feature might come in handy. By removing the wings, the RV-12iS can share a hangar with another aircraft, perhaps making it easier to find hangar space while also reducing the cost.

The RV-12iS is probably one of the most complete aircraft kits ever developed. I really liked how almost everything needed to finish the plane is part of the kit. Van’s says the only items not part of the kit are fluids and paint.

Components are divided into six subkits that can be ordered individually or all at once. The first four subkits are used to build the airframe. Next comes the powerplant subkit, which contains the 100-hp fuel-injected Rotax 912 iS and Sensenich ground-adjustable prop. Not having firsthand experience with a Rotax, I was pleased to learn that every item needed for engine installation is included.

Last, but not least, is the avionics subkit. I was impressed with the premade harnesses, which will save many hours of time. The basic avionics package includes a Dynon or Garmin EFIS, plus a transponder, com radio/intercom and ELT. Additional avionics are available as options.

Of course, having everything in the kit is one thing; knowing how to put it all together is something entirely different. Guiding you through each task are detailed step-by-step instructions. Estimated build time is 700 to 900 hours, not including paint.

Speaking of building, the RV-12iS is mostly assembled with pulled rivets, which are quiet and easily installed when working alone. Solid rivets are also used, but only in places where they can be set with a squeezer, which makes a lot less noise than a rivet gun. Keeping things quiet is important if, like me, you’re building in your garage and don’t want to disturb your neighbors.

To sum things up, the RV-12iS isn’t for everyone, but it checked the right boxes for me. With over 800 examples of the RV-12 and RV-12iS flying and hundreds more under construction, it’s obvious many other builders and pilots agree.

Marc Cook: Creature of Habit

In my job, I catch all kinds of flack. And not for the reasons you suppose, though I get it for them, too. No, it usually happens when I’m visiting a kit manufacturer or chatting with them at an airshow. I use these talks to get caught up on their current products and listen to their perspective on the industry, what kind of builder they see and a whole lot more. But in many cases, because they know I have a GlaStar, they ask: Why the heck didn’t you build one of ours?

Good question with a very simple answer. After my first stint with this august journal, I sold the Glasair Sportsman that I built in 2006 and took a sabbatical from flying. (The warning about turning your hobby into a job is valid.) When I came back, I recognized the hole in my life and wanted to have a replacement for N30KP. At the time, I performed a fairly vigorous search and considered many different designs. Of course I considered RVs, but they were already starting to gain rapidly in value and my immediate price range extended only to cover some early RV-6s with high-time engines and yesteryear avionics. I looked elsewhere, at Zenith models, various RANS designs, Kitfoxes and so on. But my search for an already flying airplane may have been driven by my disinclination to take years building again—or even waiting a year or more for exactly the right airplane to appear.

And then it did, a lightly equipped 2002 GlaStar—with, yes, a high-time engine and yesteryear avionics. Oh well. The airplane was known in the GlaStar and Sportsman circles and was already based in Oregon. As I began to consider staying “in the family,” it became ever more clear that sticking to a design I’d built before and had maintained over several years had appeal. While the GlaStar and Sportsman are different in significant details, in the big picture they’re the same—or very, very similar. What I’d learned on the first model would serve me well on its replacement. So well that I did precisely what I tell others not to: buy without a formal prepurchase inspection. Yes, I did spend significant time looking at Charlie (as he’s named) before continuing, but I knew what to look for and felt confident that the core airplane was solid and as represented.

Time has been kind to that decision, but I have to give Charlie Eubanks, the original builder, and the subsequent owners who took good care of the airplane credit as well. Are there faster airplanes on the same 180 hp? Yes, of course. Are there airplanes that carry more? Naturally. But the GlaStar fits my mission well. It’s comfortable and familiar. Plus, because it has both fiberglass and aluminum in great quantities, I can say I’m conversant in both methods. Skills that could be useful on the next one. Some day.

Photos: Jon Bliss, Jon Croke, Larry Anglisano, Omar Filipović, Mark Schrimmer.