It is a fairly well known rule of thumb that the more blades you have on a prop, the more power it will deliver for climb, but the slower the airplane will go. Aeronautical engineers like to point out that the theoretically fastest propeller would have only one blade, and while that is true, it is also very, very hard to implement, so pilots generally stop reducing blade count at two. Those with engines producing great gobs of power will generally go with three or more, gaining back speed based on sheer horsepower what they lose in efficiency.

It is a fairly well known rule of thumb that the more blades you have on a prop, the more power it will deliver for climb, but the slower the airplane will go. Aeronautical engineers like to point out that the theoretically fastest propeller would have only one blade, and while that is true, it is also very, very hard to implement, so pilots generally stop reducing blade count at two. Those with engines producing great gobs of power will generally go with three or more, gaining back speed based on sheer horsepower what they lose in efficiency.

All of that is true if you are comparing propellers with similar blade designs—but once you start really sharpening the aerodynamic pencil and optimizing blades for superior aerodynamic efficiency, some amazing things can happen—which is why props designed in recent years are showing scimitar shapes and radically interesting airfoils. In fact, the newer prop designs are good enough that they break the rules entirely—at least compared with older-designed props. Such is the case with the new three-blade Whirl Wind 300, a composite-blade, constant-speed prop that has recently emerged from the mind and shop of Jim Rust.

We recently got the opportunity to replace the blended-airfoil metal Hartzell on our RV-8 with the new propeller and have found the upgrade to be a noticeable plus in most ways. The aircraft normally flies with the metal Hartzell blended-airfoil prop that has largely replaced the older “paddle blade” design that Hartzell has produced for decades. It’s fair to say that most RV pilots who go with a Hartzell opt for the scimitar-shaped metal blades, and flight testing has shown that the minor upcharge of a few hundred dollars is worth up to four knots in speed—the cheapest four knots pilots are likely to ever buy. Our RV-8 has flown close to 2000 hours with the BA Hartzell, so it was an interesting task to replace it with the new lightweight Whirl Wind and go fly.

Meticulously Engineered

Jim Rust has been working on propellers for decades and says that the 300 series is the culmination of all he has learned both aerodynamically and mechanically. For instance, as owners of an older Whirl Wind 151 series three-blade prop, we have experience with a small amount of grease spitting (which is fixed by shimming the blades). Jim says that the 300 series blades have double O-rings to prevent this. The blades and hubs are built and machined in his shop where he can control the quality of every step.

During development, instrumentation is used to measure stress and strain as well as vibration. Props are tested at a wide variety of speeds and on different engines, and the props are actually cleared for particular engine/induction/ignition combinations one at a time to make sure that there aren’t vibration nodes that could cause problems. Refer to the Whirl Wind website to see if your engine is eligible for the 300 series—if not, check with Whirl Wind to see if and when it might be allowed. In most cases, lack of approval simply means it has not yet been tested, not that there is necessarily a problem.

The composite blades feature integral nickel leading edges for protection, and by “integral,” we mean that they are attached as the blade is formed. This is particularly important if you are going to operate off of less-than-perfect runway surfaces and will give you peace of mind if running up on gravel or a dirty taxiway. The blade shapes are carefully engineered to give maximum aerodynamic efficiency—and the process clearly works, as you’ll see in the performance numbers below.

It’s a Beauty!

The 72-inch three-blade Whirl Wind comes in a custom box that you will want to save for the day that you have to ship it off for regular maintenance. Opening it up, the first thing you see is the beautiful carbon fiber finish under the clear coat—it’s a real attention getter. The scimitar-shaped blades look exotic to old-timers but, in truth, we’ve been flying blades with that shape for years now. The finish on the Whirl Wind is wonderful though; it will really stand out in a crowd.

Mounted on the front of the airplane, the 300 series just looks mean—three blades dress up the nose of a performance aircraft in a way that is all business. For those with nosewheels, it can be a little more complicated to get the lower cowl on and off with that third blade on there. But many people do it, and it is just a matter of being patient. And for the way it looks—well worth it.

Installation

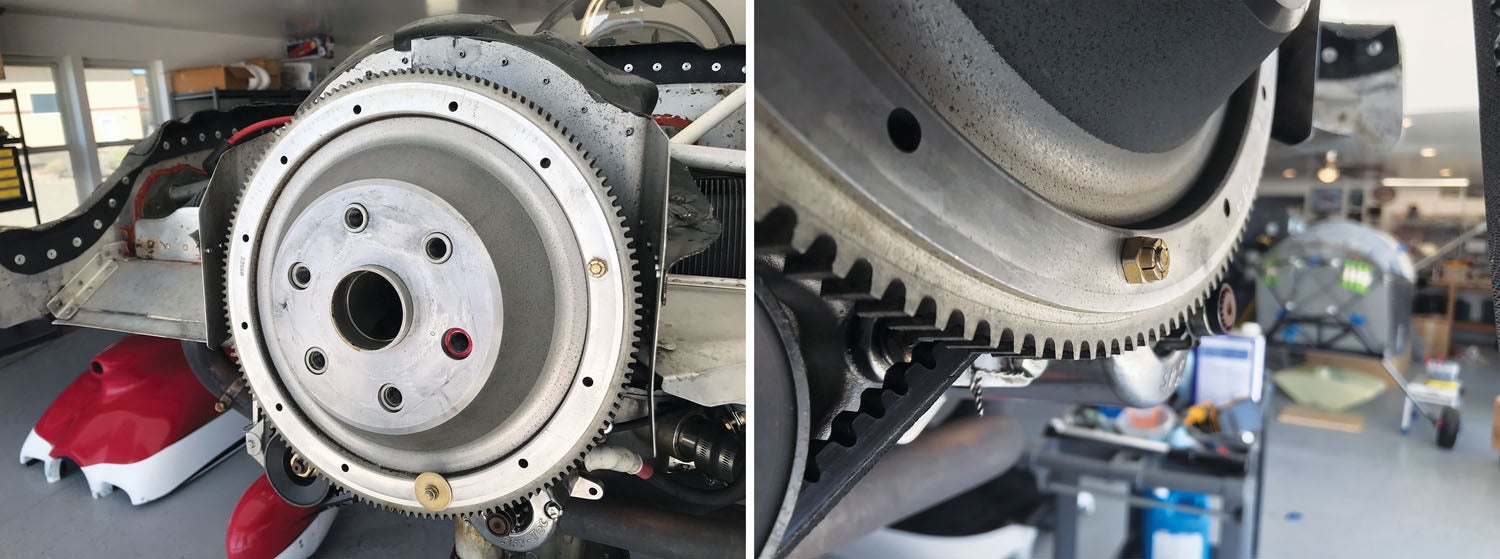

Mechanically, the swap is a piece of cake: The Whirl Wind 300 series was designed to bolt right on where the Hartzell came off, and the pre-fit spinner is spaced so that its aft edge is exactly where the standard Van’s spinner mounts on the Hartzell, so there are no changes to the cowl. Take off the cowling, cut the safety wire, unbolt the prop (yeah, it is that eighth of a turn at a time job…) and be ready to catch the oil that will spill out of the prop when it backs out far enough for the O-ring to unseat. Let it drain until it stops, then finish removal.

Bolting on the Whirl Wind is just as easy—easier, in fact, because it only weighs 36 pounds instead of the Hartzell’s 60! If it wasn’t that it was awkward, and you don’t want to drop a $12,500 prop, you could do it all by yourself. We recommend having a friend help! Torque progressively per the instructions and then get a nice tall stool so that you’re comfortable while doing the safety wire. It takes time to do it right—which usually means doing it over a couple of times—but it’s worth the effort to know that it is secure.

The spinner is, as we said, pre-fit, and you simply line it up and install the screws, which are also supplied. Our spinner came primed and ready for paint. You can probably shoot that before installation to ensure it is clean of grease and bugs, which will accumulate when you fly it.

While the original three-blade Whirl Wind (the Model 151) required a special, high-pressure prop governor, the 300 series works well with the same governor that the Hartzell uses, so there is no need to change anything on the back (or front, for a front-mounted governor) of the engine to make the new prop work. It is as close to plug and play as you can get in the homebuilt aviation world.

Post-installation work involves a ground run to ensure proper operation, including prop cycles to fill the hub with engine oil. Expect it to not cycle the first few tries—it needs to replace the air with oil in order to work. This is also a great time to dynamically balance the prop/engine combination so that you are starting with a smooth assembly from the beginning.

The Proof Is in the Flying

Our first impression of the new prop is that it is smooth—very smooth. A lot of this has to do with a good dynamic balance, of course, but the disk caught in the sun’s glint showed a very smooth surface and excellent blade tracking. Adding power on the first takeoff gave us the feeling of a slight increase in acceleration over the Hartzell, something we confirmed later when we gathered takeoff data.

The other impression you get is that the lighter prop allows much quicker engine acceleration—something we have felt on other airplanes with lightweight, composite-blade props. This, of course, means that you have less flywheel affect, so it pays to check your idle on the ground. You might find that the engine wants to quit because you have less mass out there spinning to keep it going. A slight bump up in idle speed fixes this.

Performance flight testing takes smooth air and comparable conditions, and we made sure to hold all of the variables we could (temperature, density altitude, fuel load and flying technique) constant between the Hartzell runs and the Whirl Wind runs. We tested for three things: top speed, climb rate, and takeoff distance/acceleration. In short, we found that the Whirl Wind 300 showed no measurable increase (or loss) in top speed while climb rate increased about 10% over what we got with the Hartzell BA prop. Takeoff distance (ground roll) likewise decreased about 10%, while the time to liftoff (taken from the moment of brake release with the engine developing full power) decreased from 15.3 to 14.0 seconds.

Top speed was interesting: We held the throttle wide open while varying rpm from 2300 to 2700, leaning for peak power at each data point. The data showed that the Whirl Wind developed its top speed at about 2600 rpm. Above that, we lost a knot, and below that, the speed slowly dropped off. Jim Rust said that this is normal for a constant-speed prop of this design, as is the fact that climb is going to be better with the three blades. Of significance is that the three-blade Whirl Wind produced essentially identical top speeds as the two-blade Hartzell—a triumph when you consider the rule of thumb that says two blades are faster than three.

Qualitatively, the RV-8 handling improves as you move the CG aft—anyone that has flown one with a 200-hp angle-valve engine knows that. Moving the CG aft by saving 24 pounds on the nose is the best of both worlds: a lighter ship and an aft CG make the airplane lighter in pitch and easier to fly through vertical maneuvers. Anyone with a CG in the forward end of the box and looking to move it aft without ballast might have a look at this prop as a possible solution.

Incremental Improvements

All in all, we are very happy with the performance of the new Whirl Wind 300 prop. We hope to do some additional testing against the lightweight composite Hartzell to get a better apples-to-apples comparison since the older metal BA Hartzell is not their latest design. Propeller improvement is incremental as new blades and hubs require extensive testing to make sure they are safe—the consequences of a failure are severe. For this reason, you rarely see a radical improvement in prop performance from one model to another. But if you look back several generations, the gains are very noticeable.

If you’re looking for a lighter nose for better aerobatics, it is hard not to like the new Whirl Wind 300-72. The weight savings alone is worth the upgrade for anyone wanting to lighten the nose of their RV-8. Learn more at whirlwindaviation.com.

Those props seem great. Although, since many of these homebuilts, and others, tend to have a CG near the rear limit, especially when near max gross wt.. Putting a lighter prop that far forward can make that situation much worse. Same goes for lightweight starters. I changed to a lighter wt. prop on one of my homebuilts, and it caused such a CG shift, I had to reinstall a Prestolite starter. The old big heavy type. Lyc. 160. That helped a lot. So before spending the money on one of these kinds of props, some CG calculations should be done before that.

You’re correct – going with that much lighter of a prop means that you need to think about weight and balance. In the case we’re writing about, RV-8’s tend towards nose-heaviness, and fly much nicer with a lighter nose, so the Whirlwind is great. Our RV-6 on te other hand, is always tail-heavy, even with a metal Hartzell. So….it doesn’t get to enjoy the WW, and stays with the heavy Hartzell.