In the last issue I spoke of nuclear certified string, hoping to convey that some airplane parts are just parts. Bronze bushings, PK screws, NPT fittings, fiberglass cloth, you get the idea. In this issue I’m staring design-specific airplane parts straight in the eye and calling them out as frauds. OK, not frauds, I got caught up in the moment, but also not mystical items infused with the ability to fly by secret means.

A design-specific airplane part is a combination of three things: a specific material (or combination of materials) in a specific shape and labor. That’s it. You know what that means? You don’t have to wait to get a replacement for a kit part you mussed up, nor do you need to permanently ground your one-off 1950 Huxley Hovermobile because a bird aggressively introduced itself to its leading edge.

Horse Shows and Lightning Strikes

Homebuilding is not big business. The kit aircraft industry relies on—nay, requires—suppliers both large and small. But mostly small. Small businesses are willing to take on low-volume production runs big businesses wouldn’t consider. The homebuilt industry would look very different without an ecosystem of ma-and-pa shops producing the design-specific parts we take for granted. It would be heavily populated with plans-built designs, designs born to be bred from raw materials and raw effort. The downside to ma-and-pa shops is they are often only ma or pa. During my career I saw supply interruptions caused by motorcycle accidents, anniversary cruises and horse shows. Big suppliers have their own pitfalls. They may take an initial production run of 200 spar caps, but wave off a six-unit reorder. Without Dana sewing seat cushions in a spare room in her stable, or Don machining parts in a pole building in the countryside, or the Price family developing circuit boards on their kitchen table, I dare say there’d be no kit aircraft industry. At least not one for the masses.

COVID shone a light on an always delicate supply chain. Builders are on one end; a natural resource or chemical plant is on the other. Kit companies are second-to-last in the supply chain, even for design-specific parts—even for parts manufactured in-house. A Longshoreman strike can slow or stop your project’s progress. The discontinuance of a once-common computer chip can do it. A shortage of a particular size 6061-T6 bar stock can halt tail kit shipments. Bad primer can, well, we know that story. A horse show can stand between you and your airworthiness inspection. While self-sufficiency can’t resolve every parts need you may have, remembering that airplane parts are a specific material (or combination of materials) in a specific shape and labor—and it can be your labor—may keep you making progress.

License To Build

When you purchase a kit or plans, you are purchasing a license to build one (and only one) airplane. You may not make parts to resell. However, you may use a kit part or the plans to make a replacement part. I’ll call those Personally Manufactured Aircraft parts, which, not without coincidence, share initials with the type-certified world’s term Parts Manufacturer Approval. You may know that phrase colloquially as “PMA’d parts,” where PMA also stands for “expensive.”

But even owners of certified aircraft can find parts-sourcing relief through Advisory Circular 20-62E, which allows owners of certified aircraft to make parts for use on their own aircraft. They are called Owner Operator Produced Parts (OOPPs). Whereas PMA’d parts are manufactured under license for resale, OOPPs may not be sold. Similarly, in the E/A-B category, builders can build their own parts (OOPS!) but cannot make parts to sell to others. That would violate their license to build one aircraft and infringe on the designer’s intellectual property.

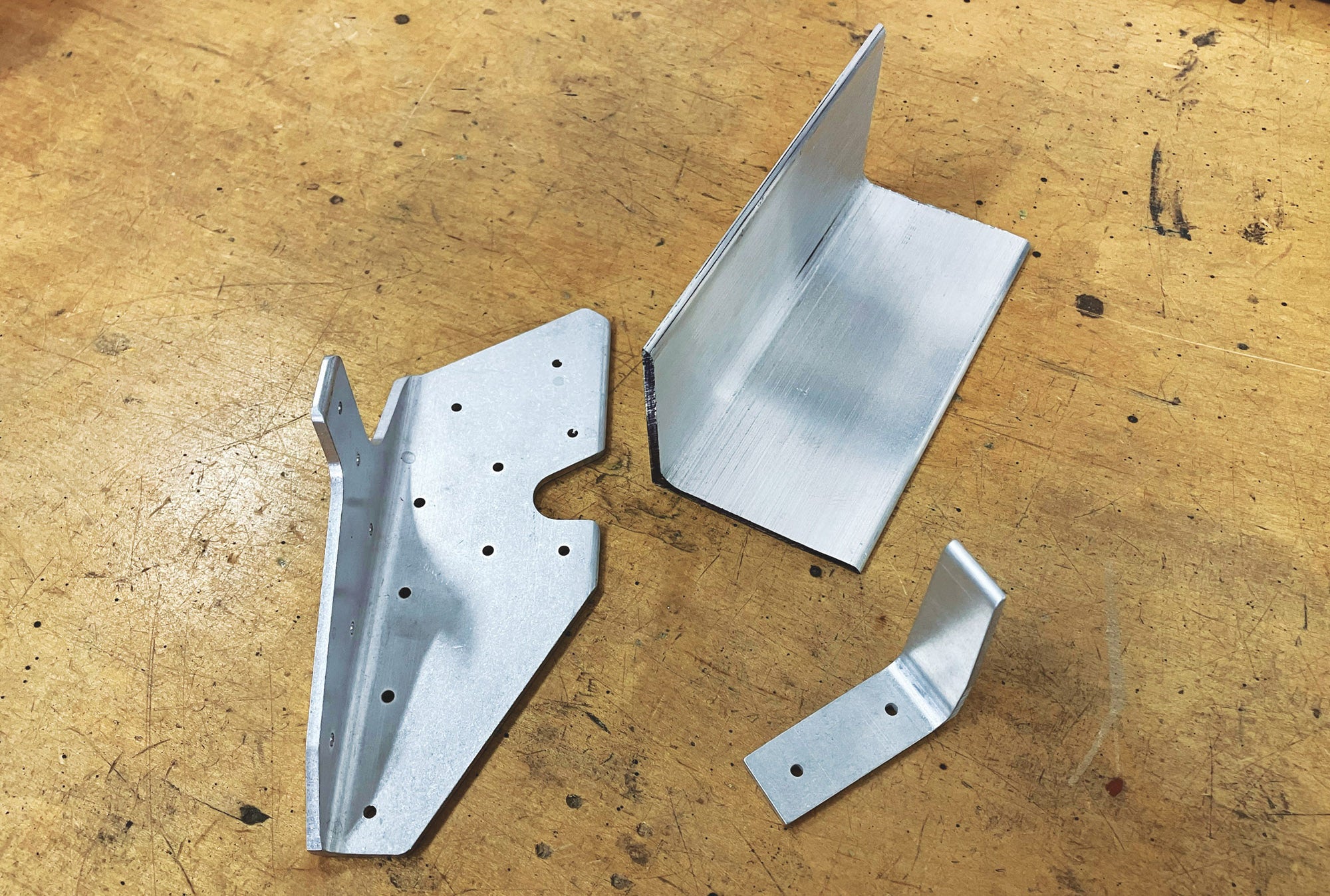

Building your own replacement kit parts, which is no different than scratch-building from plans, may save you money and time. Kit builders can forget that’s an option. During my Sonex career I saw the simplest parts ordered and I often encouraged builders to make their own.

Material, Shape and Labor

Scratch builders approach their project knowing they’ll be sourcing materials and expending their labor to sculpt raw material into the individual parts of a flying machine. When the Sonex was introduced in 1998 there were only two things you had to buy from Sonex—the plans and the spar caps—and only a few other parts you could buy. Today, few builders are ambitious enough to pound out 26 wing ribs, so Sonex, like every other kit company, supplies most of the design-specific parts premade. Still, all that differentiates a kit part from a scratchbuilt part is that kit parts use machinery to make production efficient. A rib blank is cut on a CNC router, laser cutter or water jet and formed in a hydraulic press rather than cut and formed by hand. Functionally, assuming identical materials and good workmanship, they are identical. Of course there is a cost to the machinery and factory labor that must be priced into kit-provided parts. Thus, $3 of aluminum and 20 minutes of a builder’s time is replaced by a $30 part (plus $15 shipping).

One of the first items Sonex upgraded in its early kits was to provide pre-machined spar caps. Originally, four identical spar extrusions were provided by Sonex and each builder added their labor and a bandsaw to turn the extrusions into four unique caps. Responding to a chorus of requests for pre-machined parts, Sonex accommodated the builder community—at a cost. The price of spar caps more than doubled.

Most of us won’t machine a complicated part, but homebuilders with three-axis machining capability, like followers of KITPLANES contributing editor Bob Hadley, might. Other parts would be expensive and time-consuming for most builders to build, like a blown canopy, which requires a large oven and the right temperature. A fiberglass cowling could be made by hand, though few would consider that option. Yet, it can be done. If it gets your one-of-a-kind Huxley Hovermobile flying again the time and effort may well be worth it. For an RV-6, probably not.

The steel toolbox I made in eighth-grade industrial arts was more complicated to form than an aluminum rib. The plumb bob I turned in ninth-grade metal shop was more involved than drilling two holes in a solid rod of titanium, thereby converting it into a Sonex landing gear leg. Airplane parts hold no magic. Knowing they are nothing more than a specific material bent, cut, formed, molded or welded into a specific shape can help you navigate your project with greater confidence and greater efficiency. There’s comfort in knowing you can build your own airplane parts, should the need—or desire—arise.