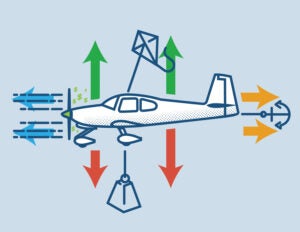

We’ve all been taught the five primary forces of flight—lift, thrust, gravity and drag. (Plus money, but it’s more existential.) Let’s focus on gravity, which in aircraft terms is weight and to which I give much respect. Weight is also often related to aft center of gravity issues, which together can amplify each other’s insidious effects on aircraft performance.

My first observational experience with mission-critical weight planning was more than four decades ago as a newly minted private pilot working at a local FBO in Boise, Idaho. A call came in from a party of four who were looking to charter a flight to a famous backcountry resort. The boss turned to a staff CFI (himself a furloughed airline pilot) and asked if he wanted to take them in the FBO’s Piper Cherokee Six. Like most professional pilots, he really wanted to complete the mission and, no doubt, earn some extra dough. However, he was experienced enough to know that big loads, hot summer days and high backcountry strips were a litany of caution flags. I could see the concern on his face as he was running numbers in his head. He reluctantly accepted the charter.

The party arrived. They were all full-sized adults with lots of gear. I was sent to fuel the airplane. I watched my instructor as he loaded the bags and equipment, and couldn’t help but notice that his hand was shaking. I had never seen him or any instructor I had flown with be so nervously focused. The big Cherokees always have a squatty stance on the ground, but as I watched them taxi out, the tail squat seemed even more pronounced.

Later that night, my boss called me at home and asked to what level I had fueled the airplane. I told him “to the tabs as instructed.” When I asked why, he told me that there had been an accident at the wilderness strip and that they had all perished. I was numb. The memory still gives me chills.

Cardinal Rules

My first “came that close” experience with weight’s effect on performance happened at my first real flying job, carrying “tourons” (a portmanteau of tourist and moron) and river runners for Lake Powell Air in Arizona. The season was only a few weeks along when my boss asked me to “haul ass” over to the Bullfrog Basin Airport to pick up a boat mechanic and bring him back ASAP. The aircraft I had been flying were Cessna T210s and T207s, the latter an incredible heavy-hauler. Unfortunately, those were unavailable, so the boss told me to take the company Cessna Cardinal. I had hundreds of hours in several Cessna types but had never flown a C177—rumored to be better at efficient cruising than load hauling. Being a recent hire wanting to impress the boss, I eagerly jumped at the trip. Flying alone from Page to Bullfrog was actually quite enjoyable; the airplane was comfortable and fun with great visibility over a stunningly scenic route.

I arrived at Bullfrog in the mid afternoon of a warm day in May. I was expecting one mechanic, but a van pulled up and out lumbered two burly types who were substantially calorically challenged. Both had a beefy tool box and one had an outdrive lower unit under his arm. I hoped only one was going with me but, no, they assured me that both had come out together and needed to return together.

As they got settled, I applied the field CG trick I had been shown on the 207. With an empty pilot seat but otherwise fully loaded, push the tail down until the nose gear is slightly off the ground and then release to see if the nose lowers back down. It passed the test, but only because a butterfly didn’t land on the tail at that moment.

Here We Go

No young wannabe professional pilot ever felt more pressure to complete a mission for the boss than I did, right there. Yet I couldn’t help but think about the awful experience with my favorite instructor in the Cherokee Six. The Bullfrog runway is bowl shaped, high on the ends and low in the middle. My thoughts were that I didn’t have excessive fuel and technically still had one less passenger than seats (albeit occupied by a marine drive unit). One concession that I made to logic and common sense was to position the aircraft on the runway with the tail over the dirt and the main wheels barely on the asphalt and then do a carefully leaned run-up to full power prior to releasing the brakes. We pilots excel at calming our doubts with additional procedures.

The gravity-assisted initial takeoff roll was surprisingly sprightly, but as we transitioned from downslope to upslope, the airspeed seemed to bog down several knots below rotation speed. Ahead, as I remember, was gently rising but rough terrain followed by steep cliffs down to the lake hundreds of feet below. Wisely or not, at the last possible moment, I rotated. The airplane left the ground but could not climb out of ground effect, and would not climb without losing airspeed. As the terrain gently rose, so did the airplane—like a terrain-following cruise missile holding about 10-12 feet AGL with a very short pitch window and a funky feel from the Cardinal’s new-to-me stabilator. Speed gains were one knot at a time, at best.

As we approached the edge of the cliff, I asked the mechanics to lean forward as far as they could without pressing the yoke, which they interpreted as bracing for impact, even though my thinking was more grasping at CG straws. At cliff crossing, it was like a floor dropped out from under us. We immediately lost altitude and rightly or wrongly, I instinctively dove for the water, hoping to gain enough precious airspeed to arrest the descent before making tomorrow’s news. Fortunately—or divinely—it worked. The mighty Lycoming O-320 drug us out of that weighty predicament with a couple of dozen feet to spare. Breathing again, I gingerly turned us toward home, enjoying about 100 fpm climb at best-rate airspeed. The rest of the flight and landing were blissfully uneventful.

Lesson Learned

I strive to entertain as much as teach with my writings, but since I hope to continue this gig for several years to come, I write the next comment in total solemnity and from the depths of my aviator soul. Never in my 35-year professional career with almost 25,000 hours have I ever—before or since that takeoff—thought for one moment that my career or even my life were in as much jeopardy as I did during the first agonizing moments of that one takeoff. Not one single one. I am quivering as I type this 34-ish years later. All that unnecessary stress just for wanting to complete a mission by challenging Sir Isaac Newton.

Most active pilots of all stripes will be challenged at some point with sketchy situations involving excess weight. It’s in our nature to want to complete the mission. In the Experimental world, we are blessed and cursed that a lot of our aircraft put a lot of Wichita’s finest to shame when it comes to performance. As the poet of internal combustion said, “There’s no replacement for displacement.” I agree. I like my ponies plentiful regardless of thirst, but we mustn’t let horsepower override brainpower, common sense or proper procedure. All aircraft, from ultralights to super heavies, have defined performance envelopes and ever-present neighboring kill zones.

Here’s a hard truth of aviation: There is a vital difference between seats installed (or the vastness of the cargo hold) and capacity available. An old-timer adage for light aircraft was that if an airplane didn’t have at least 50 hp for every seat, it wasn’t an actual “X” seater, but only a “W+2,” which means you can have full seats or full range but not both. There are, of course, some exceptions for aircraft with either minimal fuel capacity or extravagantly large tanks, but the point is the same: weight is weight. If you are power limited, the best way to preserve performance is to reduce weight. As you are building and, later, flying, keep these concepts in mind.

Build light. Build with a continuous vigilance against weight inflation. (Says the dude who installed air conditioning.) Fancy features look cool and seem essential, but if maximizing performance is a goal, build weight thrifty.

Know and use your performance data. Most of today’s advanced electronics have remarkable performance and CG calculators that are far more useful than yesterday’s generic book numbers and coffee stained chase-around graphs. Take into account that such data was calculated and proven with professional test pilots in brand new aircraft and engines, in otherwise ideal conditions. (And, let’s be honest, some numbers from the homebuilt world are strongly wishful.) Whatever the data source, it is just ballast if it doesn’t get used. Know your aircraft as well. Even identical types can vary in their real world performance whether they be a Van’s, Cessna or Boeing. Some are dogs, they just are.

Maintain situational awareness. Passengers may declare one weight but, let’s be honest, if they left that neighborhood in junior high, calculate accordingly. Other considerations like runway surface and slope as well as winds are important but should only be used as performance subtractive, never additive. Definitely subtract a tailwind, but scratch off a headwind to Lord Murphy. There’s a good possibility it could change when it’s time to go. Wind is a factor in runway performance and runway choice, but never has a direct effect on weight. Overweight is still overweight and doesn’t just affect flight performance. Being over gross can have immediate or accumulated negative effects on aircraft structure. I once read an article describing how excessive weight can affect tire alignment in some aircraft enough to increase rolling resistance. Makes sense.

Offload optional items that aren’t mission critical. If I remove my portable oxygen system, spare tire/tube/wheel assembly and swap my heavier tool bag for my carefully selected lightweight version or none at all, I can easily increase my effective useful load by 10% or more. That can be used for fuel, freight, self-loading liveware or just flying deeper into the center of the envelope. Even tow bars, covers, tie downs, extra oil and other crap we accumulate can add up. Know your mission and its limitations.

Fuel. I like fuel as much as the next guy, but there can be such a thing as too much. Sometimes an en route fuel stop is preferable and safer to stretching the range or saving some shillings in fuel budget. In the airline world, fuel isn’t measured in gallons, it is measured in pounds. I have flown large turbine aircraft for the last 33 years, and I can count on two fingers the times that I flew one with the tanks topped off. Yes, as many a bumped airline passenger or non-rev can attest, sometimes we are weight restricted and have to leave cargo and/or passengers behind.

Baggage and freight. If weight must be shed, baggage and freight usually gets bumped first because it complains the least and, in most cases, rides at the tail end of the CG envelope. One trick that many AirVenture participants employ is to ship heavy accoutrements to and from the event. Most FBOs can facilitate the same service anywhere. The shipping costs might be high but will always be lower than insurance deductibles.

Passengers. No pilot wants to deny a willing passenger, though post-run river runners who haven’t properly showered in a week are tempting. Sometimes an installed seat simply isn’t available and my vote is for the biggest galoot to stay behind—or the dude with the lower outdrive under his arm. If the mission isn’t long, sometimes a split/double trip is an option. If not, that brings us to the next…

Just say no. It can be the hardest character test any pilot is ever confronted with. I believe that the awful feeling in your gut is whatever deity you do or don’t believe in trying to save your hiney. Set your limits properly and stand by them religiously.

Illustration: Peter Jones; Photos: Shutterstock.