Dead Cow dry lake is an alkali flat a couple of big hills north of the Reno-Stead pylon racecourse but looks for all the world like a Chesley Bonestell moonscape made popular back when Wernher von Braun was selling space to taxpayers. Roughly two by four miles and surrounded by the towering treeless heights of desert Nevada, the lake bed simultaneously offers a closed arena and beyond-expansive room for the comparatively diminutive 2000-foot racecourse and maybe (maybe…) 1000 attending aircraft making up the High Sierra Fly-In. Appropriately, this stark openness is the High Sierra’s and STOL Drag’s ancestral home, the limitless space where enthusiasm can slip the leash and not bother anybody. It doesn’t hurt that founder Kevin Quinn owns 600 acres of the place, either.

And it’s enthusiasm for the open backcountry that spawned the STOL Drag phenomena. Combining the piloting skills of off-airport flying with the eternal need to see who can do it best led Quinn and friends to develop this relatively new parlor game 11 years ago. Two aircraft line up, take off on the drop of Kevin’s arm and fly to the far end where they plop the whole lot sideways to land, stop, pivot around on their heels in great swirls of dust and honk back to the starting line. There they repeat the return to earth, the winner being the first to become motionless.

Like all drag racing, a big advantage is it doesn’t take long to figure out who won. Plus, the up and back action packages nicely in front of a good-size crowd. For the pilots, it’s a busy minute, what with all the acceleration, ground effect flying and two spot landings to a hard stop in the time transport pilots spend reading back their clearance.

It’s also safe as houses—the fast boys might touch 115 mph for an instant, and all the turning is done on the ground. Still, everyone has to wear a lid.

Happy Landings

Getting there could be another thing as hundreds of aircraft converging on a single point can lead to three-dimensional misunderstandings, but a “STOLtam,” reporting points and a Unicom manned by three moonlighting professional air traffic controllers brought order to the universe, as Darth likes to say. Also helping is arrivals trickle in over several days, so unlike AirVenture, there are no orbiting dogfights over the lake. We certainly strolled in, except for augmenting our usual bounce to a landing by having much of the vertical sink information disappear when getting low over the featureless lake bed.

Discerning where to park the box kite was not immediately apparent in the face of limitless possibilities, no marshalers on duty just that moment, the odd aircraft practicing on the racecourse that we needed to cross, or which way the wind might blow, where the cool kids might be hanging and one’s tolerance for downwind-of-the-outhouse living. Quaintly aware our three-blade was blowing a fair bit of grit, and still pilgrim enough to not realize the wind was going to blow from all quadrants and it was going to rain grit for three days no matter what, we noticed the early birds were already well-roosted on the edge of the playa. So when told by Unicom to get a move on, we opted for a quick if uninspired lining up in the front row facing the open lake bed. Pull the mixture and watch the blades wheel then haltingly stop. Arrived.

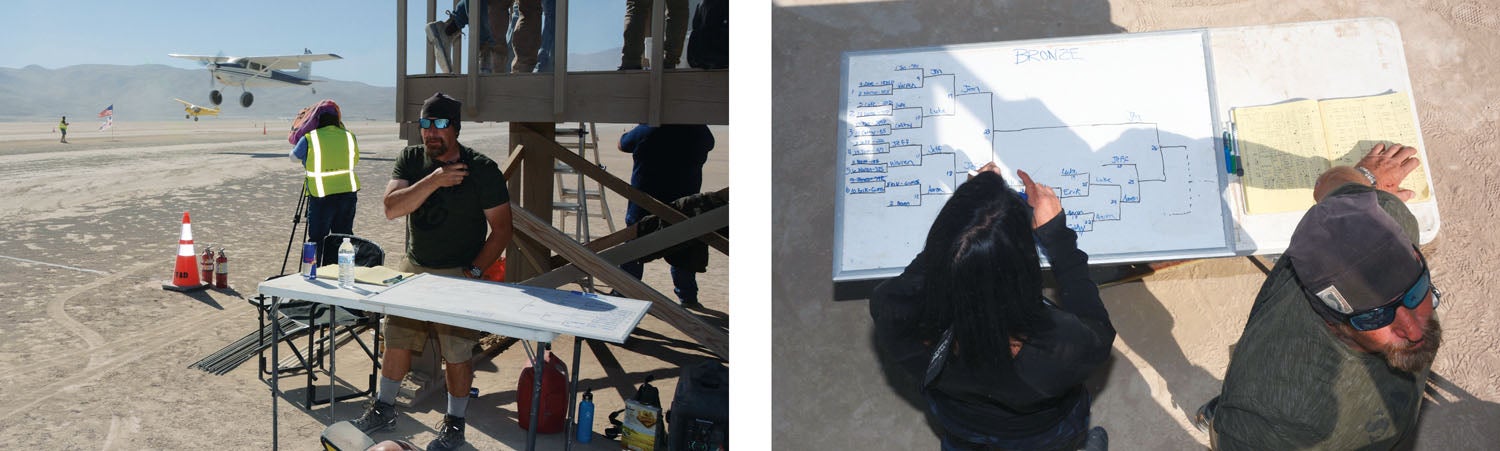

Because it’s the West, you don’t need no stinking badges—you need one of those nauseatingly yellow-green vests—so we just shed our goatskin into the rear cockpit, grabbed the Nikon and got to work by checking in with the judges at the turn-around end of the course. Open practice was eventually in progress—the schedule being unpublished, flexible and suggestive in any case. A school session having completed the day before, both the fledglings and old pros were mixing it up in our first observed session on Friday, giving us a comprehensive look between dust clouds as to who was there. As soon as the practice dirt had wafted away, the same drill was repeated but limited to three runs each and functioning as qualifying, which is set by time. We immediately saw the flying might sound deceptively simple, but as always, performing it with precision was something else altogether.

No doubt feeling the proximity of the Reno pylons, STOL Drag uses the Gold, Silver and Bronze classifications. There are no technical differences in these groupings. In fact, the hardware rules—one presumes there are rules—are refreshingly unconstrained as anything seems to go, thus the three groups merely denote practical classification by time. So refreshingly simple.

In practice, this means Bronze is populated with older Wichita tin flown slightly outside the POH at times. Slipping with flaps extended is sort of the point at the High Sierra Fly-In, after all. Mr. Quinn likes to say the exercise promotes safe flying by emphasizing stick and rudder skills used in the hills, and you can’t fault the reasoning, although the red mist of competition might intrude occasionally. Getting back to Bronze, modifications appeared limited to taking the flashlight and barf bags out of the glovebox, with pilot skill a great determinate at this entry level, which is also the required starting point for any new STOL Drag pilot. While it might seem incongruous to race pop’s 172, it’s worth remembering dirt strips were more than common in the dawn of the nuke age, and store-bought stuff was expected to work down on the farm. A dry lake bed is easy by comparison.

At the other end of the scale, the just three Gold racers present this year were all Experimentals. Each made a point of reduced weight, added drag and the sort of hot rod engine power that’s been in vogue on the dry lakes performance scene—auto or aviating—since poodle skirts. Tight little personal watercraft engines turning eye-watering rpm and wearing gearing, forced induction plus a good whiff of nitrous are standard, along with thin-chord, ground-adjustable carbon fiber three-blades.

In between was the populous Silver class, clearly home to the enthusiast mechanic with a Rotax and a mixed bag of fat-tired Cessnas augmented by craftily hammered upon Experimentals. Just the place for us.

It was all over in time for tea Friday afternoon, leaving ample time to beetle along the leagues twixt distant campsites and downtown, which turned out to be at the north (opposite, of course) end of the lake. Town square at Dead Cow was a large event tent, ominously vacant other than as an HSFI T-shirt stand, but giving blessed shelter from the wind had that been a concern and home to free coffee in the early hours thanks to the good people at AOPA. The Maryland group also had some signs about, along with a film crew and promised to choke the web with coverage. Most curiously, EAA was nowhere in evidence, no doubt due to the press of arranging another AirVenture. Mr. Quinn said he invites the feds and that they were there. But not spying any loafers and chinos, we suspect they were either in mufti or gone missing for the moment. Also present were three food trucks, a rather imposing pile of lumber-turned-firewood, and the competitive aircraft parking, which, unlike the rabble, were at least parked in mostly straight lines. It’s all refreshingly free-form, yet everyone seems to know when to go where despite no public address system or, not unexpectedly, anything approaching reliable Wi-Fi. Of the latter, we could sometimes send and receive texts, could never access email and, most curiously, did receive phone calls at the most inopportune times. Better that the electronics not work at all was the majority sentiment as severing e-umbilicals is part of the attraction of camping on a moonscape and playing with airplanes. No sense dragging in the rest of the world.

Life on the Playa

Speaking of traversing the distances, the Onewheel is the transport of choice at Dead Cow as nothing else so easily fits in an aircraft plus allows 15 miles of no-effort electric range on the lake’s hardpack. We late adopters can find the swarms of statuesque people noiselessly gliding along very Jetsonsonian, but such transport is beyond logical reproach. Besides mundane comings and goings to the thankfully plentiful porta-potties, a popular Onewheel activity was to levitate along with phone camera deployed in cinema mode, the adherents looking like incoming aliens extending a friendly hand gesture, or phaser should your imagination be bent downward by the weight of experience.

Of course, the Onewheel is demonstrably the most dangerous thing at Dead Cow, not to discount the possibility of fluff aircraft engines or (surprisingly well behaved) 12-year-olds on dirt bikes, of which there are a handful. Witness poor YouTuber Mark Patey who suffered serious derangement in an unceremonious Onewheel dismount Friday. His bounce off the playa was sufficient to snap the ball joint from the top of his femur, so he was straight to horse pistol unpleasantries while his nosewheel Carbon Cub sat unused the rest of the weekend.

Cruising the lengthy parking area by any means gave a good idea of the eclectic mix of aircraft attending. Older certified models predominated, meaning the world’s remaining Cessna 120/140s and short wing Pipers were in force. So too Cessna 180s (the T-6 of backcountry flying), no surprise there, plus a good mix of 172s, 182s, 206s, the family truckster Cherokee Sixes and their ilk in places, along with a good showing of conventional and V-tailed Beechcraft iron up to the expected handful of round-motored twins.

Fewer Experimentals showed than expected but were hardly unrepresented. Carbon Cubs delineated the top of the high-wing, fat-tire pecking order, backed by the less numerous Bearhawks and Murphy Moose. Kitfoxes, RANS and Highlanders were also never too far away, with the proceedings spiced by the odd Pilatus, pot-bellied Kodiak and distinctly franco Max Holste Broussard, each of these toting Everest-volumes of expeditionary gear. Aside from ourselves, the biplane set was represented by the instantly likable Kyle Bushman in an N3N-3, the ubiquitous Stearman, and a somewhat out of place looking Christen Eagle. We couldn’t help think of a C-47 as the ultimate transport; it certainly could carry anything, would be at home on the dirt, offer acres of much-needed shade mid-day and tentless luxury at night should one be inclined (head up, of course) to sleep inside a frozen aluminum tube. That and the oil would soak right in.

A curious tension settled over us while walking the line, a mysterious disquiet that something wasn’t quite on, not that normalcy is why we came to a dry lake bed with a name like an IPA beer. Then it hit us: the shoals of RVs were missing. It was a measure of just how pervasive the Oregon Air Force has become that, when they don’t show, we’d first notice it by some eery rent in the space-time continuum, but there you go. At Dead Cow, the RV is just another airplane—for now.

Our good time wandering among the happy campers quickly brought about sunset and the confirmation it was going to be witch-titty cold. Furthermore, we had brought precious little to eat as our sporty biplane’s carrying capacity was already near gross. Happily, the food trucks stood open apparently all hours, although the $25 per plate dinner menus suggested dieting. Even more popular was the central bonfire continually fed manly sized scraps from rancher Merrick Turner’s sawmill. Easily the activity of the evening was standing around the 100-foot fire line in a great socializing herd, individuals slowly rotating in thermal management lest they melt nylon on one side or risk freeze drying on the other. Certainly the natives were friendly, it taking no more than a couple of syllables to get a conversation off the ground.

Admittedly out of practice but having participated in our share of open-air bacchanals, plus with the HSFI often called “The Burning Man of Aviation,” we weren’t quite sure where the night’s activities might lead. But the day’s decorous organization and exuberance for clean-cut aviating carried through into the star-studded darkness. Alcohol seemed applied reasonably for taste or as antifreeze, and the closest we got to pagan worship was the parachutist practicing his deep dusk constitutional (both nights we were there, anyway) by gliding nearly through the bonfire and landing among the pre-teens milling in the periphery on their Onewheels or dad’s Razor. But he was just a parachutist.

Over 60 years of experience having finally seeped through the cracks in our skull that setting up camp is easier in daylight, we eased into our pre-pitched tent and new $300 mummy bag for a meaningful test of its 15° F temperature rating. Thursday night’s low was reportedly 18°, but we slept with both eyes closed on what was likely a 28° desert chill Thursday night.

Race Day

Morning comes whenever the Cessna 180 propeller swings, no matter the sun is still well below the eastern hills. Why in all of the FAA’s machinations the 180 prop hasn’t been banished to the wall behind the bar is one of those little mysteries, but we’re really not for any more government, even if another half hour of sleep would have sufficed. Still, the morning light was calling the Nikon, so pulling on cold, dusty Levis over long johns, we headed out to find ice in the water bottle and that stinging nip in the fingers when left outside our jacket sleeve. Lord, but the desert does stretch the thermometer.

Caffeine fans soon had the AOPA free coffee scene percolating, and for those bringing the whole tribe and a camp stove, the gorgeous morning was spent relatively dust-free (zero wind means the talc just sort of hangs where the dawn patrol propeller blew it) and engaged in breakfast. For the rest of us, it was ingratiating our way into a few electrons from neighbors with generators as the cold quickly had the camera and phone out of business and guess who left the grip with AA battery adapter at home? There is such a thing as traveling too lightly.

After a couple hours of solar lizard treatment—we’d be shedding the woolies with a vengeance by 10 a.m.—it was back to work, this time at the start line. With nasty winds forecast for Sunday, all racing was to be done Saturday, one discovered by osmosis. This was easily accomplished as even with double eliminations—each round is run twice—it just doesn’t take that long to run the races. Plus, there are no military fly-bys or drunk farmers in Cubs, so there’s generous time to enjoy the morning, run the drags and stop with plenty of time to warm up the stew while watching God play with light on the mountains.

As for the races, the crowd formed obligingly at the line conservatively set a plus distance from the action and had a good time watching the racers steadily eliminate themselves in mano a mano combat. Certainly the lower classes don’t offer the zippy mechanical spectacle of the Gold racers, but the flying is just as hard done in the Bronze as it is in the Gold. Jon Hakala, a low-time pilot in his first-ever event, won the Bronze in a stone stock Zenith CH 701.

We really enjoyed the Silver action, including the creative use of the elevator as tail skid along with some right on the money short landings and tightly matched pairs. The close racing went right to the final, where youngster Austin Clemens used the beta prop (more dirt in the air!) on his Husky to just edge a sharp-flying Nat Esser in her Kitfox SS.

Of course, the hot buzzsaw action in Gold was easily the main event and the sort of stuff worth all the dirt in your ears. With Butch Kingston’s solid lock on third in a three-plane race, thanks to two near-death cylinders, the contest was a straight-up duel between Steve Henry’s flyweight and heavily modified Just Highlander with 300 hp worth of Edge Performance Yamaha motivation and Toby Ashley’s more lightly modded Carbon Cub packing what his crew chief admitted later was 430 hp worth of Kawasaki personal watercraft engine and nitrous oxide. It was a close thing, but Ashley had that little extra oomph and might have flown a hair closer to the edge for the win.

And with that, the racing was over, and everyone could get back to hanging out in the high desert. What ceremonies surround winning the STOL Drag wait until that night’s bonfire, and then there is the issue of getting a hundred aircraft launched off the Dead Cow playa with enough daylight to get somewhere with fuel and a shower. The day-trippers were ready as fast as the spectator line could clear, and the HSFI Unicom was soon dispatching aircraft like a blackjack dealer on parallel runways (up to three can be used for staggered takeoffs). With airplanes taxiing out to the open playa, warming up and waiting in line to take off, a certain amount of dust is raised, to which nature added a stiff afternoon wind. No one was safe, and we ditched our fleeting thoughts of joining the hoard because we didn’t dare attempt striking camp in the fabric-whipping gale and sheets of blowing grit. We faced downwind and rode it out.

Those of us who stayed were rewarded with another gorgeous, nippy night around the big fire, Mr. Quinn handing out kudos, big trophies and bigger belts to the winners. Sizable aerial pyrotechnics and a suitably hard-edged country band ensued as the remaining woodpile was torched in one final blow. Soaking up what heat we could take, we marched a quick step to the tent and into the bag.

Not precisely sure how to time our exit, our decision was made easy upon waking up a tick past 5 a.m. feeling reasonably among the living, especially our bladders. Judging from the quiet pattering next door, we were already a few minutes behind our neighbor, who was indeed pulling tent pegs while a propane heater directed life-giving warmth up his Piper’s cowling exit via a length of aluminum dryer ducting. “Got 100° of oil temp as soon as I fire it up…” Smart man.

Packing was easy in the morning still as long as you held the flashlight in your teeth just right (headlight next year), and well before the sun, there was nothing left but to adjust the scarf, swing a leg onto the lower wing, grab the cabane and commit to the cockpit. Now unavoidably faced with our procrastination in doing something about our iffy starter motor, we thought good thoughts, exercised every ounce of wisdom of invoking fire in frozen cylinders along with a quart of 100LL prime and just managed to get the 10:1 Ly-Con reactor lit. Big relief.

Joining the conga line to take off, we came to easily the most challenging episode. Taxiing viz in the Starduster is for the faithful under ideal conditions, but without pavement edges as guides, the muted pre-sunrise light, dust thick as well-browned toast and traffic funneling in from three sides made it like S-turning inside a whale and fearing hitting Jonah on a Onewheel. Twice the Unicom called for complete stops by everyone as, like us, they couldn’t see the Piper 150 feet away. Other delays came from those cleared to take off “when ready” but who needed a half minute or more for the dirt of the recently departed to settle some. Used to blind takeoffs, we had no such qualms and ruefully found the dirt cloud was but 75 feet thick.

in their 850-pound, supercharged-Kawasaki Carbon Cub to reach 430 hp and squeak past Steve Henry for the Gold win.

Heading mainly east to the nearest fuel, we soon discovered the low sun and filthy windshield made S-turning necessary to identify and clear mountains. Thankfully the lack of wind allowed a westbound landing, and paper stolen from the loo along with what was left of our bottled water (not frozen Sunday morning) returned the windshield—and our glasses—to transparency. The rest was a fun 100-plus miles down to Bishop, then 300 bumpy, cold miles into a 20-knot headwind. Capital sport!

When Einar Enevoldson dead-sticked an F-104 onto it, it already had a name–Flannigan Dry Lake.

Great, near tongue-in-cheek write up to match the event’s tone. Not sure I’ll ever want to compete, but sounds like attending is a bucket list item.