Our culture’s version of schadenfreude often distills down to something called the Darwin Award, where hapless individuals appear to be disproving Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution through their own stupidity. Some of what you read has been debunked—in fact, tales of these “mishaps” fueled 18 seasons of the show Mythbusters—but the underlying idea remains undeniably true: Humans continue to do dumb things. Some get away with it every single day. Some make headlines instead.

Humans as pilots as well. Hangar lore has regaled us with stories such as the highly respected pilot and author of a successful book on backcountry survival, who, it is said, skillfully managed to dead stick a stricken aircraft on a frozen mountain lake, only to subsequently die of exposure as he had no coat nor survival gear aboard. I can’t verify that this one, among the many, is true. But I can, unfortunately, relate from experience (mine, or that of a friend, depending upon statutes of limitations) events as worthy of a Darwin Award as any.

Job One

Decades ago, I was a young, low-time commercial pilot eager to please in my first real flying job. I was captaining Cessna T207s to fly tourists and river runners around the Grand Canyon area. It was actually a very enjoyable season filled with amazing flying. A large part of this flying was based on flights in and out of the Bar-Ten Ranch airport (1Z1) on the north side of the Colorado River. In addition to being a working ranch, the facility also serves as a starting or ending point for hundreds of river-runners each season. (See “Color Country”).

I got an assignment for a morning flight from St. George, Utah, to the ranch, carrying a young employee and a bunch of supplies after the only road had been washed out by a spring storm. The ranch was desperate for supplies because a hundred or so river-runners were to be fed at the lodge that day. It was still dark when I was preflighting the aircraft as the truck full of supplies pulled up and the young lanky ranch hand jumped out sporting a huge rodeo champion belt buckle and a bulge between his cheek and gum. The bed of the pickup was full of supplies, but if ever there was an aircraft equivalent to a pickup truck, the Turbo 207 was it.

One feature of the big Cessna was the useful forward cargo area that was not only additional storage space but CG friendly as well. I grabbed a few smaller, heavier items and proceeded to stash those in the forward area while the ranch hand unloaded the truck. As I finished, I went to the rather large pile that my assistant had built up next to the aft doors. One thing that caught my attention was a large yellow can containing several gallons of diesel fuel. When I expressed concern about carrying the fuel, he emphatically responded it was an absolute necessity as the lodge’s main generator didn’t have enough fuel remaining to be able to produce the day’s lunch, let alone run the rest of the electrical needs of the lodge for overnighting guests. He then stated the phrase that has corralled many an inexperienced cargo pilot—”Don’t worry, it’s been done before.”

This was one of those infamous “mission-itis” stress moments that every pilot is sure to experience at some point. The pit in my stomach was telling me that the fuel can should be a no-go, but the young go-getter in me wanted to be a problem solver and not a problem finder. So I agreed to carry the can and acquiesced with a stern, “let’s make sure it is securely strapped down” decree, trying to act like I was wearing much more important britches than I actually was.

When it was time to go, I carefully inspected the malodorous can, hoping that the smell wouldn’t linger for flights I would be doing later in the day with passengers. The top of the fuel can was nicely secured by the cargo webbing, but it looked to need a little extra packing around the base to keep it securely in place. I grabbed a bag that was strapped into a seat and stuffed it around the base between the can and the angle of the webbing. But the young man stopped me and said that the bag was animal feed that might get contaminated by the oily residue on the can. He then swapped out the feed bag with a different bag that packed nicely around the base of the can, the webbing and the rear of the aft seat row. It was ammonium something or other. I was in a hurry with a full day ahead and didn’t pay a lot of attention.

With the sun just cracking the horizon and everything looking stuffed and secure, we climbed into the forward seats for one of the most gorgeous 20-minute flights in the world.

We arrived without incident, and the ranch truck was already waiting beside the airstrip for our desperately needed cargo. My guy and his workmate started swapping the cargo from the airplane to the truck for the short ride to the main lodge. I set about tidying up the airplane a bit to get it ready for passengers that would be my cargo for the rest of the day. Airing out the back and preparing the area for the duffel bags soon to come, I noticed some curious white granules on the carpet in the cargo area. I just swept them out with my hand and didn’t give them another thought.

Here We Go

Since I was the first aircraft in position for the day, I received the first round-trip assignment. Within a couple of hours, I had made the round trip and was back at the airstrip. This time I caught a ride with my pax up to the lodge, eagerly anticipating the chuckwagon lunch that I had helped to facilitate earlier. After a hearty lunch, I still had about 20 minutes before my scheduled flight to Vegas, so I stepped out onto the patio to relax and ponder how all these happy people around me would have been sorely inconvenienced if I hadn’t stepped up to save the day. I saw my ranch hand buddy was busily spreading fertilizer on the small lawn of the lodge. I asked him how the generator was holding up and he responded that the spare fuel we brought had been a “lifesaver.” Hearing that gave me a tremendous sense of satisfaction and a big smile. Ignorance can often be bliss.

Fast forward to April 17, 1995. By now, I was captain at my airline on the first day of a three-day trip, with the first overnight scheduled in downtown Oklahoma City and the second in Cleveland. We left OKC very early on the morning of the 18th, and all was normal. The next morning, the 19th, I flipped on the news only to be stunned by reports of the Oklahoma City bombing of the Murrah Federal Building. As the news crews panned the area displaying the damage to nearby buildings, I could see the hotel where the crew and I had stayed the first night of the trip.

Anne Faux?

Needless to say, the horrible event caught my attention in the moment, but especially in the days following when it became clear that the main elements of the explosive device were diesel fuel and fertilizer. It was what experts refer to as an ANFO (ammonium nitrate fuel oil) device. Then, like some horrible nightmare in slow motion, the events of a few years previous, long stored away in deep recesses in my brain, came gurgling to the top in 4K UHD clarity. The greasy can of diesel fuel, the convenient bag that was packed around the base, the curious white kernels on the cargo area floor and my equally oblivious partner in crime just hours later fertilizing the lawn at the lodge. With the sudden realization of what could have happened, I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. It is often said in aviation that experience helps prevent mistakes, yet recognizing inevitable mistakes and learning from them is one of the significant ways that we gain valuable experience.

On that fateful morning flight in Arizona, I had been ignorant and stupid, which, when mixed with misplaced priorities and a desire to complete the mission, could have been a disaster. Stupid enough even to warrant my own chapter in the Darwin Awards had the worst happened. I was trained and paid to put safety first, and I failed miserably, even though at the time it seemed like a tremendous success. Until that moment of clarity, I had been blissfully unaware of how close to disaster I had come.

Ignorance Is No Excuse

Over more than 35 years of commercial flying, I have witnessed a lot of changes in training, particularly with federally enforced areas of emphasis. A series of tragic events caused airline training and procedures to change dramatically. Some were security related, resulting from lessons learned after 9/11 and the PanAm Lockerbie terrorist action before that. Some reflected lessons about hazardous materials, like after the ValuJet crash that resulted from chemical oxygen generators setting off a fire in the cargo hold. Hazmat training was bulked up and fused with security issues, and a total revamp occurred on where airline training emphasis had been over the last couple of decades. Ironically, the airline guys, the very ones who get the most training on hazmat matters, are also the ones who have the least to do with the receiving, screening and loading of hazmat aboard their aircraft. They simply have to trust that others are doing their job diligently.

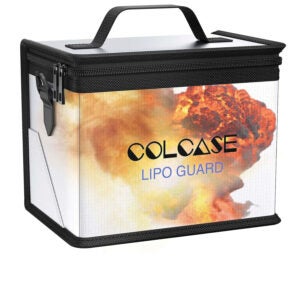

Hazmat issues are not only concerned with acceptance and rejection of materials but also the proper packaging and stowage of certain materials that fall into the ether between acceptance and rejection. Items like dry ice, stored ammunition and—a biggie getting bigger every day—electronic devices and their batteries. A couple of airline passenger issues involving batteries getting hot and a passenger on my own airplane concerned about a heating battery actually prompted me to buy a snuffer bag on Amazon for about $20 in which to seal and secure such a problem until able to get on the ground safely.

I like to fly passengers and keep my four seats in good use. Even with close friends and family, I have discovered more than a few items of “contraband” that either shouldn’t have been aboard or been better secured. For a time, I was guilty myself of carrying a suitcase that had a (very handy) integrated battery that would serve as a backup battery charger for cell phones, especially at OSH. That suitcase has since been pulled from the market and banned on aircraft.

Oh, the Humanity!

In the history of manned, powered flight, no aircraft has ever left the surly bonds of the earth without hazardous materials on board as both human bodies and every fuel source this side of a Guillow’s rubber band falls into the category. A whole litany of common household and shop products can be hazardous in the wrong place at the wrong time. The challenge and responsibility is to wisely manage the necessary without compounding hazards with the unnecessary.

As someone who, through ignorance, could have stumbled into infamy by raining down on the Grand Canyon in a crimson mist, I encourage all of us to regularly reassess our knowledge and practices concerning hazardous materials. There are several resources available in the training marketplace and, if suffering from insomnia, federal advisory circulars and the like. Don’t be unfit for the gene pool. Know what’s on board and, perhaps most importantly, learn when to say no.

Photos: Bill Repucci, Shutterstock.