Like the proverbial frog who doesn’t know that the pot of water is getting warmer, it is easy to adapt to an airplane or engine that is slowly going out of tune. We get used to compensating for a small change, then compensating a little more and then (hopefully) realize that “this is getting ridiculous!” and decide it’s time to fix something. Nowhere is this more true than with engine idle speed and idle mixture adjustments. It is hard to detect minor changes as they develop, and it’s only when you have the engine quit on roll-out or the airplane just gets too hard to start that we take action.

Our fuel-injected RV-3 is a good example. We’ve been flying it for a dozen years now and while we originally tuned it for sea level (where we lived when we built it), we have been flying it at altitude for many of the past years. We were reluctant to change the really nice factory settings that caused it to purr at lower elevations, with the justification that we do fly down there occasionally. I finally got tired of having to manually hold the engine above the idle stop so that it wouldn’t quit. My wife flies the airplane as much as I do, and she likewise had learned to compensate. But when she had some hot start troubles on the way back from AirVenture last week, I figured it was time to do a complete re-tune.

Digging out the manuals for the Silver Hawk injection system (a billet-machined version of the Bendix MA-5), I re-acquainted myself with the simple procedure: warm the engine up, clear it out with a mag check, then set the idle speed to about 750 rpm and finally set the idle mixture by checking the rpm response to a mixture sweep to idle cutoff. A 50-rpm rise is just about perfect.

Well that’s great if you can get it to idle with the existing idle mixture setting, but ours was blubberingly rich, so we had to take a WAG at leaning it out before setting the idle. How did I do that? I started with the engine running and brought the throttle back as far as I could without it quitting, then leaned the mixture back until it smoothed out. Then I brought the throttle back a bit more until it got rough, then leaned it out a bit more—leaning with the cockpit mixture lever, not the idle mixture. I did this several times until I got it to a smooth idle and noticed that, yeah, it was really leaned out, so the settings must be stupid-rich. This didn’t exactly show how much to spin the idle mixture wheel, but it told me that it wasn’t a matter of one or two notches—we’d start with something like half a turn.

I don’t know about you, but the older I get, the less I like sitting with my arms and head just a few inches behind a spinning prop. When I think about watching professional mechanics tuning an engine “on the fly,” I realize that they were all young or had young assistants twiddling the knobs. Older and wiser, I enlisted my wife! No, not to tune it with the prop spinning, but to let me stay in the cockpit (and not climb out after every run) while she made adjustments in between. It was far quicker than climbing out each time—and easier on the body!

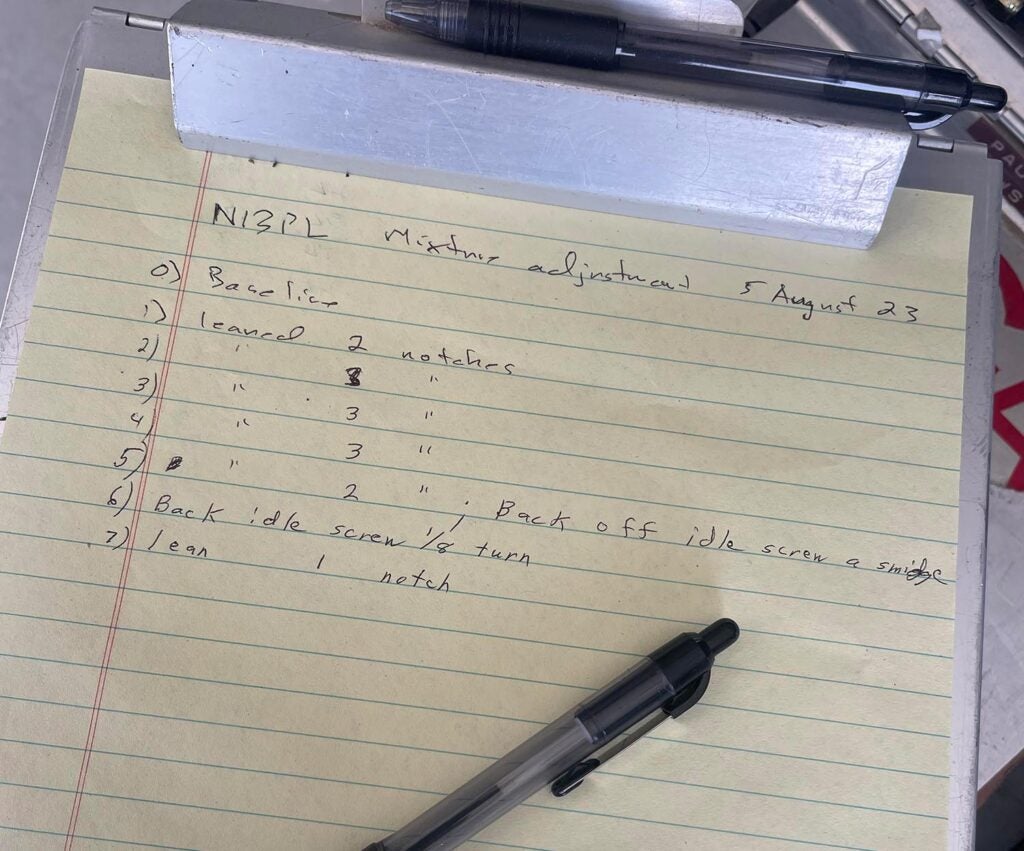

I’d make a run and determine how much I wanted her to lean it, after shutting down. She’d make the adjustment and, importantly, record it. There’s nothing worse than forgetting where you are from your starting point, in case you have to return. Then I’d get her clear, start back up and see what I wanted next. For each run, we noted how much we leaned the idle mixture (in thumbwheel notches) and then could add them up to figure out how far it was off at the beginning.

I progressed with leaning while manually holding idle until it was clear that I could get it to smoothly idle at about 750 rpm, then we set the idle stop for the throttle and proceeded with the usual tweaking of idle mixture to get the 50-rpm rise at shutdown. It only took six runs, which wasn’t bad considering how far out it had drifted. Now the interesting thing will be to keep an eye on it as our local density altitude goes up and down with the seasons and see how much adjustment it wants.

One further thing I did was to put a piece of tape next to the mixture lever indicating where our best-power setting is for our usual altitude, as well as a mark for ground idling (which also turns out to be very close to our lean-of-peak-EGT cruise setting). It’s interesting to note just how far back this is in the mixture travel. For those of you (like us) who fly mostly in the mountain west, it shows just how far back the mixture lever should be for a high altitude take-off or go-around. That old “mixture full rich for take-off” checklist item is most definitely wrong once you start flying with density altitudes above 6000 feet!

Having learned to mechanic on mostly carbureted engines, I have always been just a little less comfortable with tuning fuel injection, referring frequently to the manual to refresh myself. But truthfully, it is about as simple as adjusting the idle-mixture needle valve on a carb, so if you aren’t happy with yours don’t be afraid to adjust it. If you keep records as you go, you can always return it to a known state if you really foul it up. And maybe you’ll reconsider letting some sub-optimal part of your airplane’s performance slide because it’s changed so slowly.