You have the big sunglasses and a fat watch…hey, cant fly a plane without em. You even swagger past the Cessna and Piper types, because you’re building your own airplane. And then you come across a guy like Walter Treadwell…and its suddenly, undeniably humble pie time.

Like a lot of other men, Treadwell got into aviation via WW-II. However, he did it with an amazing bit of timing; after landing from his student solo, he expected to be congratulated, but instead he was grounded. It was December 7, 1941. In short order, though, he was back in the air as an Army Air Corps instructor, training others to go to the front lines. After three years of it, the opportunity came up to fly B-25s in attack mode with the famous 345th Group “Air Apaches,” strafing and skip-bombing Japanese ships.

After the war, Treadwell was just another guy looking for a job. He stayed in the reserves doing the occasional weekend hop until 1955 when he rose to become chief engineer of a company making those enormous cranes that load containers onto ships. But something was missing…flying. So, in 1985, after 30 years of walking, he marched into a ground school and took lessons, first in a modest Cessna 150, then on to qualify in seaplanes.

Missing Links

But something was still missing. Hed been a bit of a model airplane enthusiast for quite awhile, so, refreshed pilots license in hand, it seemed only a matter of scale to build a Lancair 235. After flying it for a couple of years, he needed another project, something a bit different, something more challenging.

Having dug out the big glasses and fat watch, the next accoutrement had to be a scarf. And that meant a plansbuilt Jenny JN-4. Three years later he was in the air, but there was that itch again.

While a military pilot, he finagled a ride in a P-38 Lightning. The memory of it must have activated his Walter Mitty gene, because in short order he decided to build his own P-38. “Hey, no big deal. Just make it all wood, add a couple of Suzuki auto engines, design and build a landing gear and go fly-easy!” How big? Well, whats the wingspan thatll fit in the hangar? Answer: about half size.

Like the real thing, the aircraft was dangerous to other pilots. Its so authentic looking that the first time this author saw it, a trip to the chiropractor was needed for a sprained neck.

After a couple of years of flying his own P-38 and shooting down Cessnas, the itch returned. Turns out it was the seaplane endorsement that needed scratching. Santa Maria, California, used to be a training base for P-38 pilots, so Treadwell asked the museum if it would like a half-scale version. The short answer: Yes!

Onward and Upward

Part of the motivation of the P-38 was that flying a single engine over the Trinity Alps in Oregon was a bit scary. So if a twin-engine P-38 was safer, a twin-engine with the ability to land on water would be even better. Combine that with about 1000 miles of freshwater rivers not that far away in the delta just northeast of San Francisco Bay, plus being a boater for years, and the choice seemed obvious.

What was not so obvious was the amount of help he might get. Hat in hand, Treadwell went to his EAA chapter to ask for volunteers, and about a half dozen members raised their hands. That was in October 2003, and, with the extra hands as encouragement, he started a feasibility study.

Now consider that there is not a single, original example of an S-38 in existence. Not one. Not in a museum, not in a private collection. Zero. So there was a lot of research to figure out what went into one. However, the task was not quite like recreating the Mayflower in that there are two S-38s flying. One is a scratch-built replica named, and the other, named Osas Ark, has only the original tailbooms and upper wing. Treadwell was also able to acquire a set of the original 1928 factory drawings and a lot of documentation from books and videos.

A Good Fit

The next problem was to resize it to fit in the hangar (there’s that limit again). The original was 6500 pounds empty, 10,480 pounds maximum, with a 75-foot wingspan, and it carried eight people plus a crew of two. If he simply shrunk it to fit his tee hangar, it would be too small for an adult.

The solution required some aerodynamic engineering to keep it large enough to carry people, and small enough to fit in the hangar. The result came in at about 2200/2800 pounds and a 41-foot wingspan, with the cabin dimension reduced to 64% height, 55% length, 75% width. This way it fits two passengers and a crew of two.

Treadwells engineering background came into play when he wrote an extensive program to generate values for drag, propeller size, center of gravity, center of lift and all the other numbers that give one a sense of confidence on that first flight.

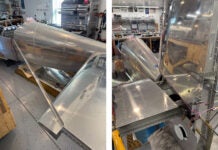

The next deviation from Sikorskys design came in the materials. The original had a hull of hardwood covered in Duralumin and wings with a Duralumin spar covered in fabric. Treadwell decided to use wood and fiberglass for the hull, and wood and fabric for the wings.

Authentic to the original, though, is the entry: Pilot and co-pilot enter through doors just aft of the windscreen, while passengers climb onto a tire, over the lower wing, left foot on a small step just aft of the round window, onto the top of the fuselage and down through a small hatch. When everyones aboard, the hatch slides shut just as is done on many a sailboat of today. The original had a pair of 420-horsepower Pratt & Whitney Wasp engines, so it seemed only natural to use two new Rotec nine-cylinder radial engines from Australia for power.

Where the Project Stands

With about 4000 hours invested so far, Treadwell figures another 2000 or so ought to do it. He says hes working 4 hours per day, six days per week, and there are the occasional helpers such as Ken Coe and Gordon Jones along with others.

As to the date of a first flight, well, Treadwell is sanguine on the subject: “Itll fly when its ready,” he says. That pretty much describes the attitude that is needed for a project such as this one. Just build one piece at a time, build every day, and one day you’ll surprise yourself by having a finished airplane. As for the mini-AgCat? He built that to have something to fly while working on the bigger project.