The Big Toot Tommy Meyer built is not the two-seat biplane his father envisioned. “It was going to be a side-by-side version of Little Toot, with longer wings like a back-staggered Beech,” said Meyer. His father, George W. Meyer, “was going to use Monocoupe landing gear with the wheels turned backwards, where the wheels were pointing forward, and he was going to cover the wheels with GeeBee-type wheel pants. He said it was going to be a Big Toot for Mom and Dad to go flying in.”

The Big Toot Tommy Meyer built is not the two-seat biplane his father envisioned. “It was going to be a side-by-side version of Little Toot, with longer wings like a back-staggered Beech,” said Meyer. His father, George W. Meyer, “was going to use Monocoupe landing gear with the wheels turned backwards, where the wheels were pointing forward, and he was going to cover the wheels with GeeBee-type wheel pants. He said it was going to be a Big Toot for Mom and Dad to go flying in.”

A skilled metalworker who worked for Curtiss-Wright and later the U.S. Navy at several aircraft maintenance depots, George Meyer designed and invested six years building Little Toot, a single-seat homebuilt biplane that first flew in the early 1950s. He named it after the Walt Disney character that had possessed his son, Tommy, Little Toot the tugboat.

A few preliminary drawings were as far as his father got on Big Toot, said Tommy, now 75. “As time goes by, Dad developed brain cancer and then cancer in the lungs. Before he died [in 1982], Dad said, ‘Tom, if you get around to it, would you build Big Toot?’ I said, ‘Sure, I’ll do it!’ It has taken me 20 years to develop the pay grade to do such a thing.”

He started work on Big Toot in 2003. “I’m not an engineer,” said Meyer. “I don’t have the wherewithal to build the airplane he envisioned.” But as an engineering draftsman he could build a larger version of Little Toot, and the drawings he worked from are the legacy’s primary familial link.

“My dad told me, I don’t care what courses you take in junior high and high school, but I would like you take one course every year, and that is drafting. You can learn so many things as a draftsman, geometry, how to figure things out on paper. I did that every year through two years of college.”

While Meyer was in high school, Arlo Schroeder wanted to build a Little Toot and pestered his dad for plans. Because he’d built the biplane for himself, it had little more than rudimentary drawings and sketches, Meyer said. “Dad said they were so bad, people can’t hardly read them, and he asked me to redraw them.”

With Rapidograph pens and a LeRoy set, he completed the drawings in three months. The title block reads: “Designed by George W. Meyer. Drawn by George W. Meyer. Traced by Tommy Meyer.” For builders who didn’t possess his father’s master metalworking skills, in addition to Little Toot’s original monocoque tail cone, Meyer drew a fuselage that was all welded steel tubing.

Meyer recreated the Little Toot’s drawings again when his employer at the time, Mobil, transitioned its draftsmen from pen and ink to computer augmented design. For training, it encouraged them to provide their own practice plans. Today, with a CAD system and roll printer in his home shop, Meyer can produce full-scale drawings for every part of Big Toot, and almost every part of Little Toot, allowing builders to use them at 1:1 patterns.

Designing Big Toot

“If I can draw it, I can build it,” Meyer said. To make room for Big Toot’s second seat, he extended the steel-tube fuselage 3 feet, and “I made it wider (27 inches wide to the outside of the tubing), so big guys could get in the thing.”

Contrary to biplane convention, the pilot-in-command sits up front. “Everyone told me I was crazy to do this,” said Meyer, “but that’s where the pilot sits in all of the tandem Van’s Aircraft RVs.”

Joe Flood, who has logged a lot of biplane time, including both Toots, approves of the position. “You can see over the nose in both of them, so you don’t need to S-turn when taxiing.” Both cockpits have controls—stick, throttle, rudder pedals, and brakes—so the back-seater can land the biplane, if needed. Only the front has instruments and avionics.

Big Toot inherited the structural limits of its predecessor, said Meyer. Working at the Naval Air Station Corpus Christi, his dad shared Little Toot’s designs with the aircraft depot’s structural and aerodynamic engineers, said Meyer. “They agreed that the airplane would be good for plus or minus 10 G, just as my dad calculated.”

The wings are identical, except for their span; Big Toot’s “are two bays (18 inches) longer on each side, and they have full-length ailerons on the lower wings,” Meyer said. Employing a NACA 2212 airfoil and 42-inch chord, the lower wings are straight. The upper wings sweep aft at 8°; there is no center section. Double flying and landing wires brace the wings on both Toots. Hefty cabane struts hold the upper wings above their respective fuselages, with gusset plates on Big Toot.

After decades of helping builders restore and create Little Toots, Meyer incorporated the accumulated improvements that solved problems and simplified maintenance in Big Toot. The fuselage is fabric covered behind the cockpit. Removable sheet metal panels cover the forward half. “You can totally expose the forward fuselage top to bottom. That makes it easier to work on the avionics, instruments, and brakes, so you don’t have to go cockpit diving.”

Interior panels keep the cockpit clean and unobstructed, and Meyer painted all of his panels inside and out. Screws hold the panels in place, and Meyer swears by DeWalt’s gyroscopic electric screwdriver. A motion sensor activates righty-tighty, lefty-loosey, with the degree of wrist rotation controlling the tool’s rpm. With it, he can remove the panels in about 3 minutes.

Building Big Toot

Without apology, Meyer describes himself as a sentimental person. “If you think that you can build an airplane and say you built every part of it without asking someone for help, you’re the biggest liar in the world.”

Look closely at Big Toot and you’ll see the names of those who helped Meyer. Some are under the horizontal stabilizer, and all of them are on the fuselage fuel tank, what he calls the airplane’s “time capsule.” Neatly painted on the 6-gallon header tank between the pilot’s feet, part of the inverted fuel system, is Meyer’s dedication to his family legacy: “In loving memory of my father, George Walter Meyer, final request and dreams, build Big Toot.”

Big Toot came to life in Meyer’s well-equipped home shop, which might double as a showroom for Mittler Brothers tools. “I have $250,000 in Big Toot,” he said, and a good portion of that went to the Wright City, Missouri, company for metal brakes and shears, a tube notcher, and beading tools that will repay Meyer Aircraft’s investment by making parts for the Toots.

Early in the project, Meyer met and became friends, and later partners (see sidebar), with Kelly Swafford, pilot, airplane builder, engineer, and CNC machine magician who owns and operates the R.K. Swafford Company, which specializes in production and prototype machine design and repair.

Interested in buying a set of Little Toot plans, “He stopped by the shop when I was cutting out ribs and asked what I was doing. In explaining, I said it took about three hours to build a rib after I cut out all the parts. He asked if I had some of that wood so he could show me how quickly he could cut out the parts.”

Swafford returned several days later with stacks of perfectly cut wood. “This should make building those ribs a lot faster,” he said, “and I cut me some out, too.” (Swafford has since CNCed a one-piece rib from an aluminum billet.)

Meyer gave the rib pieces to “a friend, Phil Witt, a model airplane guy who had a heart attack and the doctor wouldn’t let him do anything strenuous; bored, he asked for something to do; he built the ribs for Big Toot.”

The ribs are 1/8-inch ply with 1/2-inch spruce cap strips. The spars have aluminum crush plugs, so tightening the bolts that pass through them will not damage the wood’s grain. To position those holes, Meyer printed full-scale spar drawings and glued them in place. He measured again before making holes, and “it was off only 1/32 from one end to the other.” Steen Aero Lab provided the seamless, preformed plywood leading edge.

He employed full-scale drawings for the fuselage as well. Working on a level table topped with particleboard, he pasted the profile drawing (left and right sides are identical) in place and screwed oak blocks to position the tubing. “The Mittler Brothers notcher does a beautiful job, producing a nice joint for TIG welding.” After tack welding both sides, he applied the bottom drawing and stood the sides on it.

With the fuselage fully tack-welded, Meyer mounted it in the rotisserie he made. The rotating fixture is essential. “To TIG weld well, you need to be comfortable. Final welding on the fuselage takes hours and hours, and you need to work on different joints so the heat doesn’t build up and distort the fuselage because of asymmetric expansion.”

Little Toot got its landing gear 6.00×6 wheels from a Cessna 120. With a 260-hp Lycoming IO-540 in the nose, Big Toot would need longer, stronger legs, so Meyer turned to Grove Landing Gear Systems. With the necessary specs in hand, Grove designed the one-piece gear, fitting it with Grove axles, brakes, and 6.00×6 wheels.

With the same size wheels, Little’s wheel pants streamline those on Big. Like the wheel pants on a Cessna, Meyer said, a center bolt holds the pant in place. Over time, they can come loose, so he designed an aluminum teardrop that fits on the outside of the pant and keeps the wheel pant nut on the axle from coming loose.

Cockpit & Cover

A side-hinged canopy covers the pilot and passenger. When closed, grabbing one of the round, red Gold Medal popcorn popper knobs slides it fore and aft to position six stainless steel locking pins into their fuselage-mounted fairleads. “I got the idea from the Pitts Model 12 canopy,” said Meyer. He drew the canopy with 9 inches of head clearance in the back seat and sent full-size drawings to Jeff Rogers at Airplane Plastics. “A place in Dallas bent the square tubing that makes up the canopy frame.”

Hooker Harness’s ratcheted aerobatic double belt and shoulder harness secures the pilot, and an array of upholstered and embroidered seat cushions position the pilot and controls; a standard belt and harness holds the passenger in place. They control their individual cockpit comfort with NASCAR air vents.

A GRT Avionics EFIS dominates the panel, with an EIS engine monitor mounted on a subpanel. To its left are the turn coordinator, vertical speed indicator, and three-axis electric trim controls and position indicators. (Meyer removed the roll axis while addressing the airplane’s aileron issue.) To the right are the altimeter, airspeed indicator, Trig Avionics TY91 com and TT 21 transponder. The day-and-night VFR airplane’s switches and circuit breakers are on the right-side panel.

Meyer covered Big Toot with Poly-Fiber and a lot of wet sanding. He learned the secret to “absolutely smooth leading edge from a Little Toot builder, who explained that wrapping the upper and lower fabric around the leading edge and back to the forward spar didn’t need tape.”

Meyer made it even smoother by sticking a layer of white felt over the pre-doped leading edge. “When you shrink the Poly-Fiber, it compresses the felt smooth. The only tape you need is where the wingtip hits the first tip rib.” In addition to pre-doping the covered structure with Poly Tak, Meyer “melts the edges of the pinking tapes into the glue with a Monocote iron.”

Grady O’Neal of Glo Custom, a light aircraft painting company at the Toots’s home field, Northwest Regional Airport (52F), north of Fort Worth, Texas, was getting ready to retire, Meyer said, “and he wanted Big Toot to be the last plane he painted.” He copied the scheme that adorns Little Toot. A Dallas-area artist recreated Little Toot’s whistle and created Big Toot’s father and son tugboat artwork.

The N-number, N64LT, unites Little Toot with its designer’s EAA member number, which EAA reassigned to Tommy at his father’s passing.

Firewall Forward

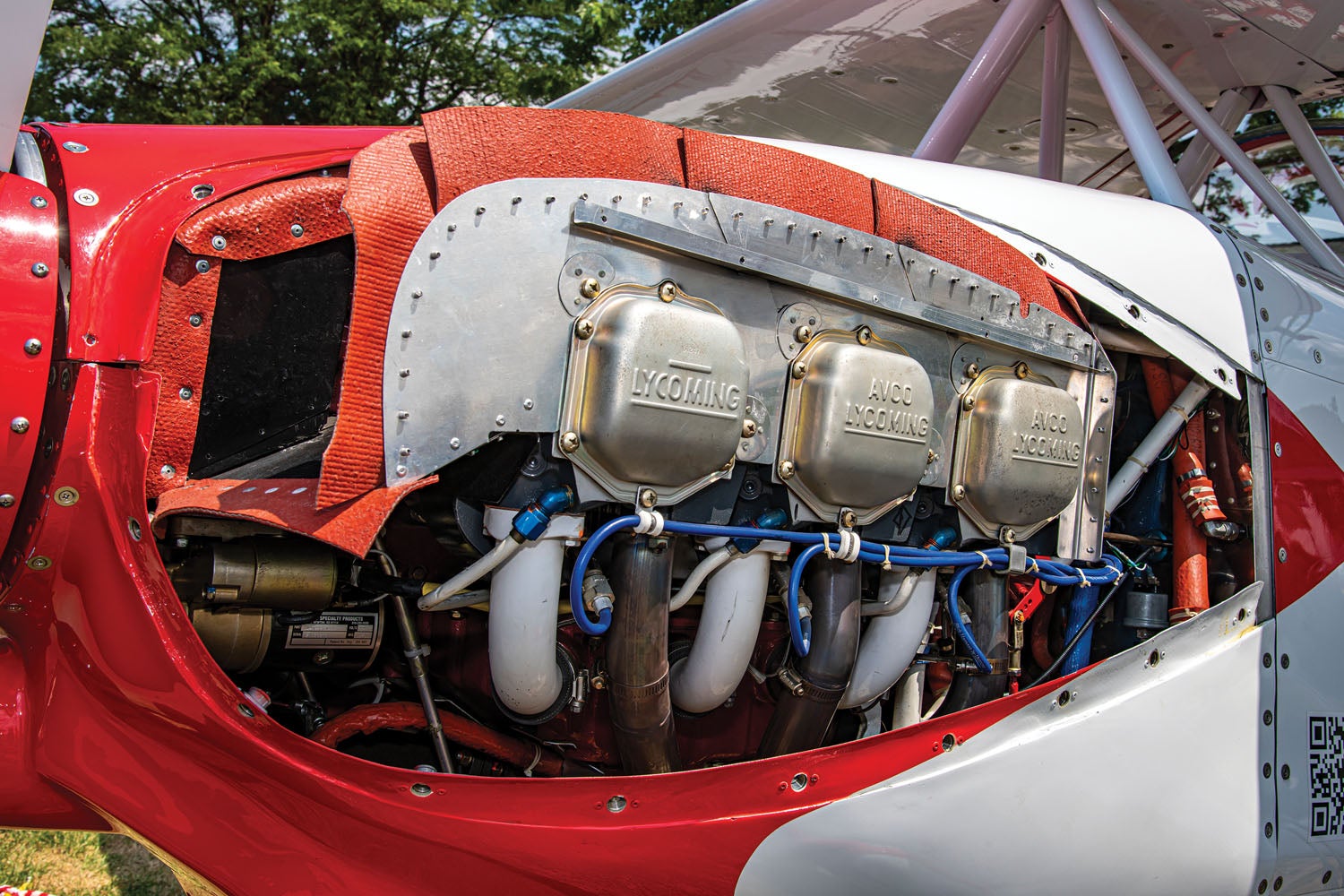

Little Toot flies behind a 150-hp Lycoming, and Meyer wanted the commensurate power in its two-seat sibling. To build engine mounts, he found a holed IO-540 case with the same mounts as his new Lycoming.

Meyer mounted a 3/8-inch-thick steel plate to the table his dad used to make engine mounts and glued Toot’s firewall drawing to it. In addition to the necessary holes, the drawing includes the thrust line, along which the crankshaft should align.

To achieve this, Meyer mounted a dummy crankshaft to a 15.5-inch round steel plate with four holes tapped for 3/8-18 bolts that enable the necessary offsets (2° down and 2° right, measured with a digital level) when the plate is mounted over the thrust line shown on the drawing affixed to the table.

To mount and move the case on the aligned crankshaft, Swafford made slip sleeves so Meyer could locate the starter ring where it needed to be in the cowling. “When it was all locked in place, I installed the mounts and engine rubbers and welded it,” said Meyer. “It’s just near perfect.”

Deeming the exhaust system “above my pay grade,” Meyer trailered Big Toot to Dusold Designs in Lewisville, Texas. “Mike’s an artist par excellence, but he’s not in the aviation business. He does race cars.”

Dusold fitted the IO-540 with a ceramic-lined, stainless steel exhaust system that collects the six cylinders into two Saber Stacks “tuned like musical instruments,” Meyer said. Injectors used in a race car’s nitrous oxide system squirt smoke oil into the exhaust. Without a fuselage connection, the exhaust “moves with the engine because the two big augmenter tubes are held by a trunnion that bolts to a boss on the bottom of the oil pan.”

Two removable 9-gallon fuel tanks in the upper wing supplement the 22-gallon fuselage tank through valved lines. In addition to the 6-gallon header tank, there is a 2-gallon smoke oil tank behind the cockpit. In addition to a cockpit indicator, a calibrated dipstick accurately measures the main tank’s contents.

The wing tanks are removable because, “given time, all fuel tanks leak,” said Meyer. Nestled in 1/4-inch bays gusseted to the spars, 3/16th-inch clips secure the tanks covered by aluminum panels that look like the surrounding wing thanks to their beaded false rib marks.

Phase 1 testing revealed gravity wasn’t sufficiently moving fuel to the main tank. Lift’s lower pressure was “sucking fuel from the vented cap,” Meyer said, “so Kelly designed and built the stand-tube fuel caps that pressurize the tanks with ram air.”

Cowling the Lycoming was one of Toot’s top challenges. “Bug eyes” is what Meyer calls the cheeky air inlets on Little Toot’s cowling. With his dad’s molds, he wondered if it would fit the IO-540. “They fit perfectly! All I’d have to do is split the cowling down the middle to make it fit top and bottom.” After hours of sculpturing, scraping, and sanding the new mold of foam and filler, “it really breaks your heart to break the plug out of the mold.”

With all of its pieces in place, Big Toot got on the scales. With its front-seat pilot, 260-horse Lycoming, and Hartzell constant-speed prop, its center of gravity was at the forward limit. Putting the pilot in the back seat really wasn’t an option because there were no instruments, so Meyer looked at the prop and its governor, which weighed 74 pounds.

Seeking a solution, he called Catto Propellers. “Craig said, ‘Give me all the specs on the airplane, and I’ll build you a prop that weighs only 22 pounds.’ I sent him the specs with a cruise-speed goal of 155 to 165, and I had the prop in a week.”

Pressed for time in preparing Toot for its EAA AirVenture 2018 debut, there wasn’t time to build the three-bladed fixed-pitch composite prop with the optional nickel leading edges, so pilot Joe Flood avoids rain. First-flight challenges delayed Toot’s AirVenture debut.

First Flight

Big Toot made its first flight on June 6, 2018. It didn’t go well. The pilot said the Frise-type ailerons, which counteract adverse yaw by dipping a leading edge into the slipstream below the wing’s surface, fluttered at 130 mph. “I’m not going to lie to you,” said Meyer, choking up, “It just destroyed me. I put the airplane away.” Kelly Swafford came over later, Meyer said, and told him “We’re going to fix the airplane.”

Having already made a number of parts for the airplane, Swafford had many of Toot’s drawings, Meyer said, but not the ailerons. “I sent him those drawings, took the ailerons off, and met him at his shop at 6 o’clock the next morning to balance them in a fixture he’d made that included a sensitive scale.”

The aileron’s trailing edge weighed 1.2 pounds, and Swafford started adding weight until they balanced, Meyer said. “Then Kelly did the math to figure the mass of the counterweight and CNCed a mold to cast counterweights that fit the aileron’s leading edge perfectly. There’s 10 pounds in each wing, and we designed new aileron hinges to carry the load.”

After putting everything back together and doing another weight and balance, Joe Flood, who’s logged a lot of biplane time, including Little Toot, went flying. For three days, Flood flew, filled up, and flew again, and the ailerons never wiggled. “Talking on the radio, I said I needed a top speed, and Joe said I’m doing 210 now, and that’s where we redlined it.”

With a 40-hour Phase 1 test time, Gary Grubb of Hangar 10 helped fly the tests, said Meyer, who doesn’t now fly for medical reasons. Meeting at an outlying airport where he could fly some aerobatics, Grubb said Meyer needed to change the redline to 230, adding, “This airplane is fixed, and it’s made for hot dogging.” It is not a two-seat Pitts, added Flood, “but it has a respectable roll rate of 360° a second.”

With the ailerons balanced, the only Phase 1 squawks were oil pressure issue, caused by a grounded wire, and overly warm oil temperatures. “Toot’s bug-eyes push a lot of air through the cowling, and we didn’t have the oil cooler baffled right,” said Meyer. “New baffles fixed that.”

Accompanied by Little Toot, Big Toot made its EAA AirVenture Oshkosh debut in 2019. Proudly parked by Homebuilt Headquarters, few passersby did not stop for a closer look. This included the homebuilt judges, who awarded the 2018 Meyer Special Big Toot, N64LT, an EAA Plans Champion Bronze Lindy.

Photos: Richard VanderMeulen, Tommy Meyer & Scott M. Spangler.

Excellent article and I can validate the very large effort that Tommy put into this airplane. I worked for his dad when Tommy was still a boy and we reconnected years later and I stand in awe of the labor that Tommy put into Big Toot.