Airplanes are designed for particular missions. Some are simple ultralights designed to lift you off the ground for a few minutes in the golden hour of evening light. Some are fast performance cruisers intended to whisk you and your baggage across the country in short periods of time. Others are designed to ring out your vestibular system with high-rate aerobatics—or to plunk you down on a short rough strip beside a secluded lake in the mountains. Trying to use a point-designed aircraft for a purpose other than what it was intended for often leaves one unsatisfied. No matter what the purpose of the airplane though, it is important to remember that someone took the time to design and build an aircraft for the niche in which it lives. And some of those niches are fascinating to explore—and to experience.

Airplanes are designed for particular missions. Some are simple ultralights designed to lift you off the ground for a few minutes in the golden hour of evening light. Some are fast performance cruisers intended to whisk you and your baggage across the country in short periods of time. Others are designed to ring out your vestibular system with high-rate aerobatics—or to plunk you down on a short rough strip beside a secluded lake in the mountains. Trying to use a point-designed aircraft for a purpose other than what it was intended for often leaves one unsatisfied. No matter what the purpose of the airplane though, it is important to remember that someone took the time to design and build an aircraft for the niche in which it lives. And some of those niches are fascinating to explore—and to experience.

The AirCam is one such airplane, something that clearly was designed for a particular purpose—for a specific mission—and one that throws some conventions to the wind in order to accomplish it. I have heard it described as a pterodactyl merged with a canoe. It’s an ungainly description that some might think insulting, but is actually descriptive of an airplane with a singularly interesting mission. The AirCam was, in fact, designed to be used as a photographic platform in remote terrain—Africa to be exact. And its design has proved to be spectacularly successful as a low-and-slow, wide-open photographic machine with plenty of performance, rugged construction and excellent redundancy to keep you from becoming a pedestrian hundreds of miles from civilization.

Kitplanes has reviewed the AirCam before (“AirCam Adventure,” April 2009) with glowing endorsements for both its mission capability and its sheer fun flying experience. But that was years ago, before my tenure with the magazine. Despite my good intentions and desire to fly as many different aircraft as possible, it was only recently that I finally found the time to get together with designer Phil Lockwood at his Sebring, Florida, base where the AirCam kits are produced, to sample this delightful aircraft and report on just how enjoyable the “AirCam Experience” can be.

Design Philosophy

The AirCam grew out of Lockwood’s earlier work on the Maxair Drifter, a design he bought when Maxair went out of business. Lockwood had been approached by photographers working on a story for National Geographic to help them learn to fly their Drifter in remote Namibia, and this created a relationship between him and folks wanting to do aerial photography in other remote locations. When National Geographic approached him again for a project in the Ndoki rainforest of the Congo, Lockwood realized that flying low and slow over unlandable terrain far from civilization in a single-engine airplane carried a significant risk.

He recognized that what they really needed was a twin-engine airplane with those same low and slow capabilities that would fly just fine if one engine quit, so he proposed the design of what became the AirCam. It was accepted, and the result is the line of aircraft that we see coming out of Sebring today.

I have always thought of the AirCam as a fairly large plane, probably because when you walk around Sun ’n Fun or AirVenture and run across one on floats, it towers above everything else. Even on wheels, the nose sits fairly high—but this is deceptive because that nose is sticking a long way forward of the wing, and with a taildragger, that puts it up fairly high. You can also generally walk under the wing because it is essentially a parasol design, so the effect is of a large machine. But in fact, the wingspan is just 36 feet, the same as a typical Cub. So think of a twin-engine Cub with 200 horsepower, and you get an idea of the performance capability. Even with half power, a Cub can fly away from most runways, so this is a pretty reasonable way to ensure that you aren’t going to be hiking out of an alligator-infested swamp or a rainforest filled with beady-eyed creatures if one of your engines lets you down.

The airplane was designed to be easily broken down for transport over rough terrain. The wings are easily removed, with the center section remaining attached to the fuselage. Pictures on the AirCam website of the original Congo expedition show the fuselage being towed on narrow logging roads through the jungle, while the wings are being carried by two people. Since the empty weight of the entire aircraft is around 1100 pounds, breaking it down into smaller sections makes it transportable by simple methods in places where high-tech transport isn’t available.

Of course, the real magic of the AirCam for a photographer is the view, and this was what made the design with the long skinny nose so desirable in the first place. Lockwood has kept this feature, even while adding a third seat (which sort of takes up the space that was used for baggage in the two-seat version), and even that third seat has a pretty good view.

Improvements in Recent Years

The current version of the AirCam is what Lockwood refers to as “Generation 3,” and not just because it will seat three people. It is the third iteration of the basic design, capable of a higher gross weight and with the ability to fill the space behind the second seat with either a lot of cargo or—yes—a third seat.

Accommodating the third person was really a matter of adding reinforced structure for seat belt attachments and adding footwells alongside the second seat so that the rear-seater has a place to put their heels; a flat floor can be terribly uncomfortable after a while. In addition to the provisions for the person, the structural bulkhead that is sort of the heart of the fuselage—where the wing struts and main landing gear attach—was strengthened.

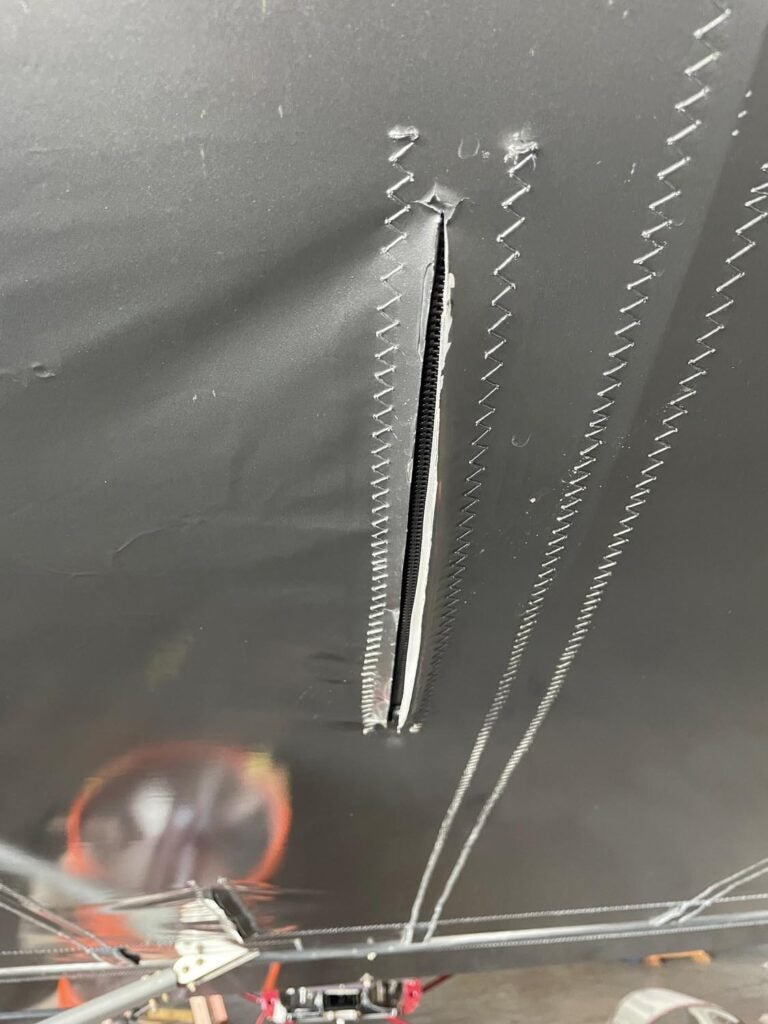

In addition to these improvements, the latest version can be had with a variety of options, including a full enclosure for flying in a lower-noise environment, as well as flying in wet weather. While one of the joys of the AirCam is that open-air feeling, I have to admit that flying with the enclosure still provided exceptional visibility while keeping things a little less frenetic in the seat. The enclosure can be installed and/or flown in multiple configurations—with just the front cockpit enclosed in the bubble, with the front bubble and side panels for the second seat as well, and with or without the side panels for the rear cockpit/baggage area. The front bubble is impressive all by itself, and a bonus is that you can taxi with it open, so that it can be left open until the moment of flight in a hot environment.

The options list also includes floats, of course, and many AirCams are mounted on amphibs so that they can truly be used just about anywhere. Strictly speaking, AirCam provides the mounting and rigging package as a kit option, but they can also arrange for the float package itself. Remember that to fly the AirCam on floats, you need a multi-engine sea rating. Fortunately, Lockwood aviation can help you out with that, since they have special authority to provide such instruction in the AirCams that they own.

Lest you think that an airplane designed to get explorers into the backcountry of the planet is necessarily primitive in the cockpit, the airplane we flew was equipped with a Garmin G3X Touch screen in the front cockpit, as well as a com radio, intercom and ADS-B In and Out. Although it had backup instruments for airspeed and engine rpm, the single screen was more than enough to do the job we needed to do—fly the airplane and enjoy the view outside.

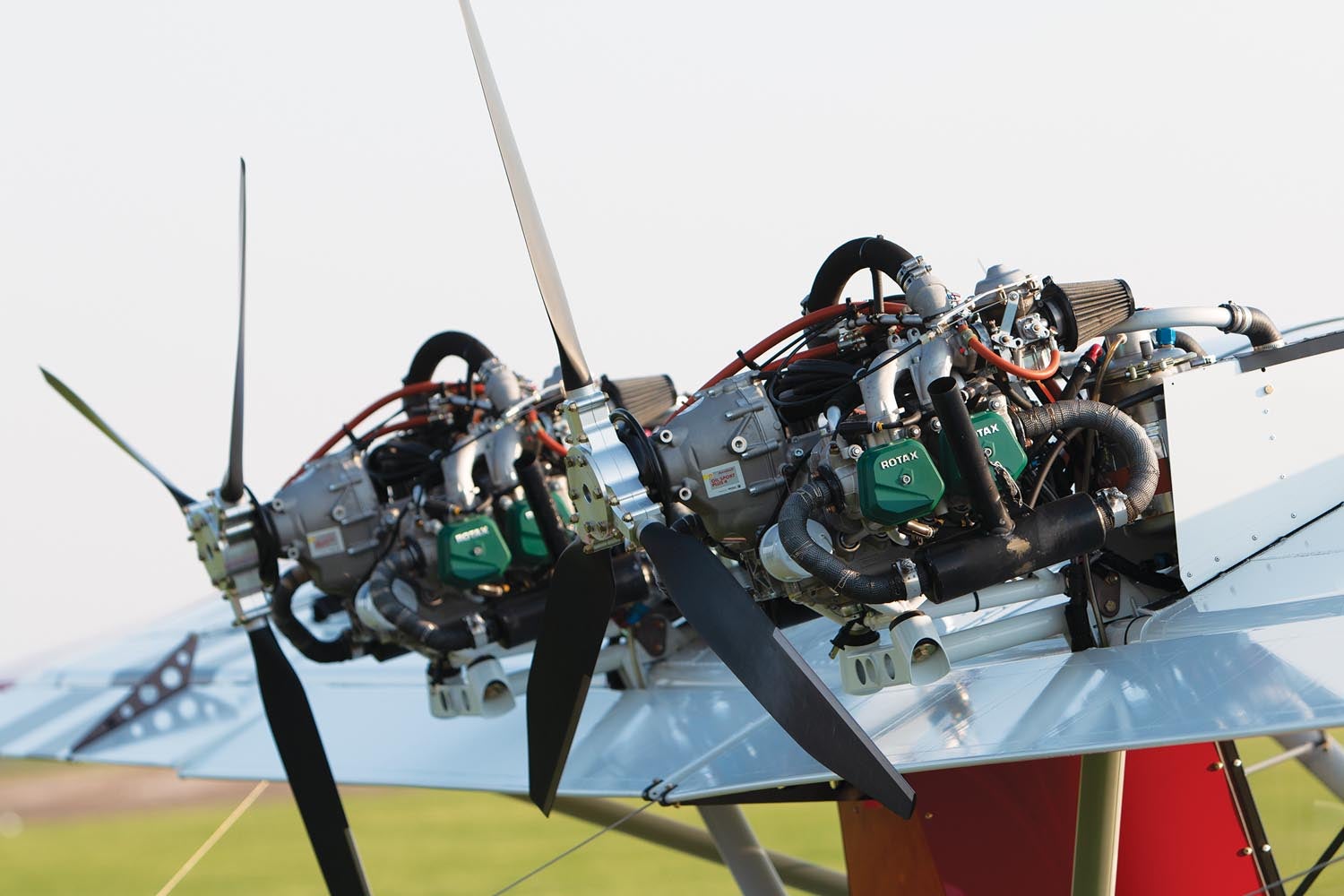

The kit is available in segments (fuselage, tail and control surfaces, wings and finishing kit) as are many kits today, for those who want to spread out their expenses and/or storage. Engine options include the Rotax 912 ULS, 912 iS or the turbocharged 914 UL for those who want an extra 15 hp per side. One thing we noted about the engine installation is there is no cowling or baffling to build or attach—the engines just bolt on top of the wing and live in the open air. Having built enough airplane cowls to enclose numerous engines myself, as well as having attached a small turbine to the top of my SubSonex, I can speak to the huge time savings of the AirCam installation, and Lockwood said that when they have tried a cowling, they got no appreciable gains in either speed or cooling—it just took more time to build.

How Big Is It?

As I mentioned earlier, I tend to think of the AirCam as a very large airplane. Possibly this is because on floats or wheels, it stands tall. Possibly it is because of the fuselage length (a tandem-tandem that will hold three people or two with a lot of baggage). And possibly because it’s a twin, and twins are supposed to be large.

But the truth is, this airplane has the wingspan of a Cub—not an airplane that we associate with the word “large”—and it has a maximum gross weight of 1900 pounds. With an empty weight of 1100 pounds, that leaves 800 pounds for fuel, people and gear—not bad for a twin-engine “Cub.”

At any rate, once we opened the hangar door and I really walked around the machine, I realized that it really is right-sized—not excessively large, but tall enough to walk around comfortably. The fuselage does give you that “canoe” feeling because it is narrow, and you are sort of sitting on top of an aluminum canoe. But that fuselage is what makes this such a fun and wide-open airplane to fly. With the wing mounted well aft (or the nose a long way forward—take your pick), the visibility is simply astounding. From the front seat, it is hard to even see the wingtips, and the low fuselage sides don’t get in the way when you look almost straight down. This is indeed a great seat in which to put a photographer.

The airplane we flew was a taildragger on wheels. We had our choice of that or the amphibian, and I chose the landplane for my first AirCam adventure so that we could truly concentrate on it as an airplane and not overload my short flight with the boat aspects. We’ll definitely have to go back and get wet!

With the airplane sitting on its ample tailwheel, the front seat is elevated enough that the boarding step is welcome when getting into the airplane. The middle seat is a more normal height, of course, but we wanted to see what it was like up front. The seat is comfortable and has ample width, despite the apparent narrowness of the fuselage.

Side consoles mount the few switches needed to make this twin-engine airplane operable—a pair of mag switches for each engine, a single starter switch, shared between the two motors, fuel pump switches, a toggle switch for trim and some light switches—that was about all that was required. The panel sported a G3X Touch EFIS, a single com radio, seat heaters and some circuit breakers. No, this is not an IFR airplane, nor is it intended to be one. It has just what you need and nothing more.

The seat is adjustable on the ground with simple pip pins—one on either side—to hold the seat in an appropriate hole. The holes are one inch apart, so pick your inseam length, and choose the right one for your comfort level to the rudder pedals.

The airplane we flew was equipped with the front-cockpit enclosure: a large bubble canopy, hinged behind the pilot, that swings down and latches to keep you dry in rain and keep the wind out of your hair. We’ll have to go back and try one with a simple windshield to get the full open-cockpit experience, but for our first exposure, this was enough to still experience the visually open nature of the front seat. We were able to taxi with the bubble in the up position because with twin pushers, there was no big slipstream of prop wash to make the concept frenetic.

Starting the two Rotax engines was a simple matter of turning on the mags and fuel pumps, then holding the start switch to the left position to crank Number 1, and after it was running, doing the same thing with the switch held to the right for Number 2. The G3X is happy showing engine data for two engines and that is the only instrument you actually need, making for a clean, simple panel. Of course, there were a couple of backup round gauges, but we have gotten so used to flying with EFIS displays, we didn’t even notice them in flight.

Taxiing the AirCam confirmed my impression that it is not an overly large airplane. In fact, with good differential brakes and twin engines, it is very maneuverable on the ground. Lockwood demonstrated how easy it is to spin on one wheel (it was his tire to wear down, but it certainly didn’t flat spot), and our trip to the run-up pad was uneventful. Once I recognized that the wingtips were no farther away than they would be in a J-3, I relaxed about clearance and found it easy to move around.

The run-up was simple, and with the engines warm, we moved out to the runway and levitated. With that much power and a big wing, there really isn’t any other description—by the time both throttles were wide open, the tail lifted, followed by the mains, and we were up and away. Think 200-hp Cub and it becomes clear: Getting out of a small field surrounded by tall trees is this airplane’s bread and butter.

How Does It Fly?

The first thing we noticed—and that Lockwood had briefed us about—is that you really do need to keep on the rudder to initiate turns because of the large ailerons and resulting adverse yaw. This is a true stick-and-rudder airplane, and it expects you to fly it coordinated, unlike so many fast homebuilts these days that let you get away with lazy feet. Lead with a little rudder as you roll into the turn—just like a sailplane or a Cub—and you’ll have no trouble.

We climbed out of Sebring airport to about 2000 feet agl to get out of the traffic pattern and headed south toward Lake Istokpoga, a couple of miles away. Before we let down to examine the sightseeing capability of the airplane, Lockwood asked if I’d like to try a stall and examine the single-engine capability of the plane. Sure, I said, and throttled back while raising the nose. Unlike so many high-wing homebuilts these days, many of which never truly break and simply mush along while setting up a good sink rate, the AirCam gave a nice little shake as the nose dropped, essentially recovering itself via the break. I added a little power without stuffing the stick forward—simply relaxing back pressure is enough—and the airplane flew away with a loss of less than a hundred feet of altitude. The stall was straight-ahead and docile.

For the single-engine demonstration, Lockwood pulled the left engine all the way back to idle—the fixed-pitch props require no control or thought—and we simply kept flying along at the same altitude at a slower speed, with one foot farther ahead than the other. To echo the power-off stall, the airplane was completely docile on one motor. We slowed down to VMC, with Lockwood wiggling and waggling aileron and rudder, and it showed no signs of wanting to roll over and die. This is a twin that makes even a rusty multi-engine pilot look good. With the engines mounted relatively close together, it is getting close to centerline-thrust territory.

With the low-speed stuff out of the way, I throttled back the other engine and pushed the nose over into a descent toward the lakeshore. We reviewed the rules about staying 500 feet away from any person and structures on the shoreline and settled into a cruise at about 60 knots maybe 10 feet above the water and reeds of the large but shallow lake. This is what the airplane is for!

Low and slow but not excessively slow—sightseeing slow—is where the AirCam excels. Handling is good. Just put it where you want it, and if you miss the perfect picture of that bird in the reeds, just circle around for another try. The airplane points well and goes where you ask it. The nice thing about it being a twin is that being this low is relatively safe, as we found out when we pulled the engine up high. Nothing bad happened and the airplane didn’t settle. This is nice when you’re 10 feet off the ripples because you won’t go swimming if the engine bobbles as would happen in a single.

The airplane also has plenty of power (and wing) to climb when you see an obstacle or peninsula up ahead and you want to climb over it, then settle back down on the other side. We do a certain amount of low-level flying in high-speed aircraft out in the desert, and it is a very high-gain activity. But sightseeing down low in the AirCam was relaxed—although we of course stayed vigilant for the fishing boat in the reeds. No need to disturb their peace and quiet. Slowed down to 60, the twin Rotax engines weren’t working very hard, so we weren’t making much noise anyway. The birds we passed over barely gave us a glance, hardly aware of or disturbed by our approach or passing.

An hour passes quickly when you are out having fun like this, but the clock showed it was time to head back to the airport for landing. That, of course, meant we had to climb up to pattern altitude, which seemed almost like a great height by now! Approaching the field on an upwind, we heard a Cessna call in as a straight-in from 8 miles out. Doing the math, we figured we could easily fly a crosswind entry to a full pattern before he made it to the runway, so that is what we did, keeping it close just so we didn’t slow him down. I flew the close pattern without speed guidance from Lockwood. I just did what felt natural, and aside from needing to remember to lead with rudder in the close-in turns, it really felt like I was tooling around in a simple, high-drag single.

The final approach was necessarily steep because we were in close, but the dragginess helped bring us down, and as we approached touchdown, Lockwood asked if I was going to three-point or wheel it. I told him I’d go for the wheelie because it was easier than finding that perfect three-point attitude on the first try, and as it turned out, the landing was a piece of cake. The nice thing with pusher props is that you can push forward after touchdown without any concern at all of a prop strike.

Overall, the AirCam is a fun and easy airplane to fly, with lots of margin for mistakes or failures. The visibility is astounding. In fact, if I was carrying a photographer, I’d put them in the front seat and fly from behind (that would be the middle seat in the Gen 3 three-seater) because then you’d “just” have normal visibility for the pilot. The airplane is stable and goes right where you want it to go, and that means you can poke it into all sorts of interesting places—just as it was designed to do.

Sheer Enjoyment!

Whether you have a specific mission for the AirCam—a scientific study in the Amazon, photographing sea life in remote locations or exploring the polar ice cap—or you just want an airplane with a unique ability to amaze with safety and slow-speed capability, the AirCam is worth having a look at. And not only is it useful—it is just plane fun! It is one of the only multi-engine kit aircraft out there on the market today, making it even more unique. And if you put it on floats, you double the fun and the places you can take it.

The AirCam is not another fast aluminum or glass ship that will get you places or fly aerobatics on a moment’s notice. But if your goal is the sheer enjoyment of watching the earth go by as you cruise over the surface at an intimate altitude, it should be high on your list. You can fly as low and slow in a Cub or other backcountry airplane—but you can’t do it with the visibility you get from the front seat of an AirCam.

I’m itching to fly this thing on floats really bad. It is my screen saver, so I don’t forget to go to Sebring FL as soon as I sell our second house…. And maybe build one.