We’ve come a long way from the Narco Omnigator (vintage 1958 or so) to the latest glass gizmos that do everything except make the morning coffee (and that’s an option for next year’s model).

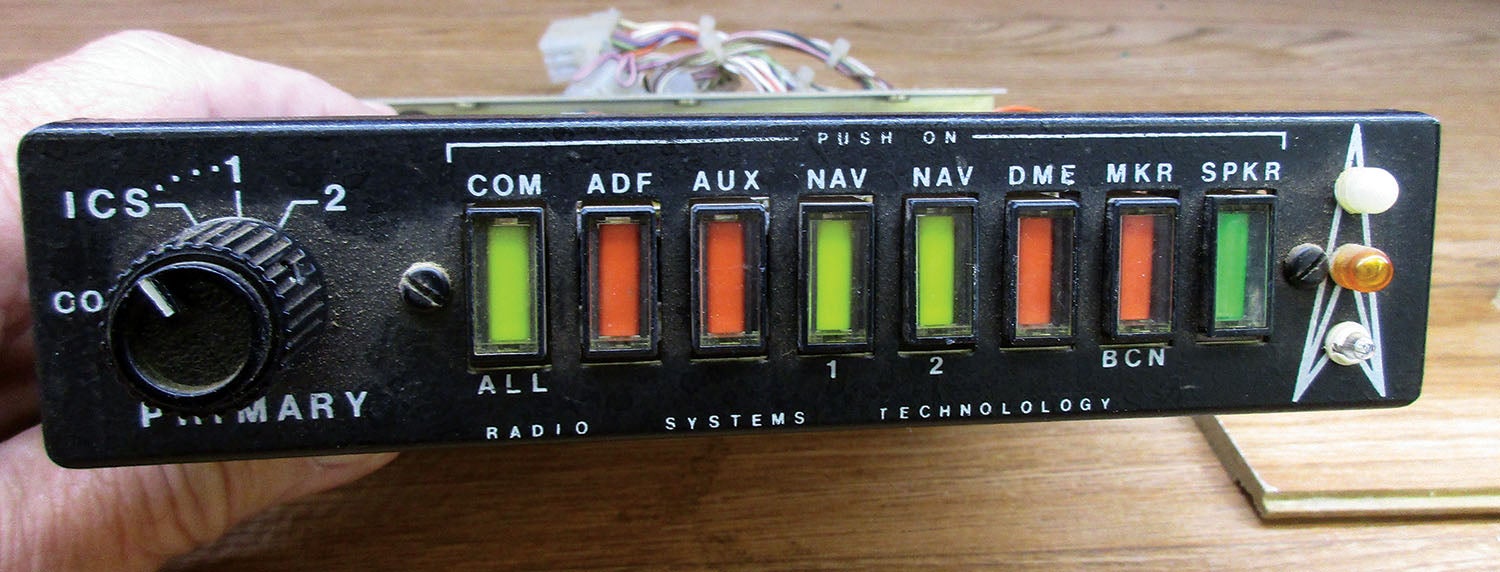

What has not changed a lot is the little switch box audio selector panels that route the various audio signals to and from our headsets. Yes, some designs now come with a digital voice recorder for instant replay of incoming com audio, some have Bluetooth adapters for wireless headsets, and some go so far as to offer stereo on the “music” channel.

Most come with provisions for two com radios, an intercom, and an “aux” channel for monophonic music. Most are for 12/14 volt systems; very few work directly on 24/28 volt ships.

A quick search of a few popular aviation parts catalogs shows most of the bare-bones panels knocking hard on the $1000 door (that’s 1 aviation monetary unit [AMU] when talking to the War Department about airplane expenses). Some of them are in the 3 AMU range, and with both of them, that’s not including installation.

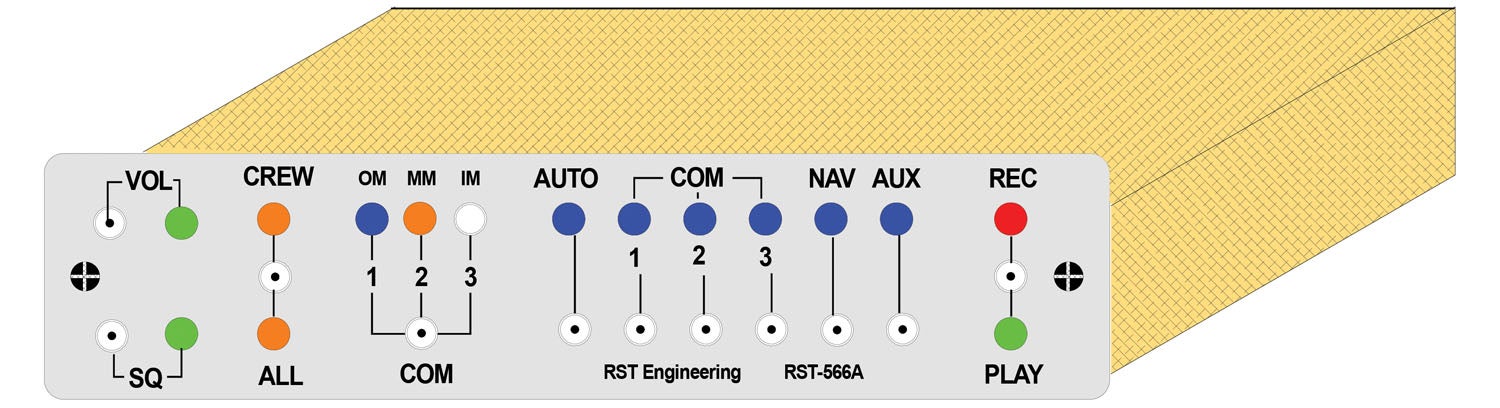

Let’s put our heads together and see if we can come up with a bare-bones panel that is less (hopefully a lot less) than half the price of the store-bought units. What should this panel have as a bare minimum?

- Capability for two separate com radios

- An “Auto” switch to switch both microphone inputs and headphone outputs simultaneously to the selected com radio

- Pilot and copilot headset inputs and outputs

- Two passenger headset inputs and outputs

- One NAV circuit with four separate parallel inputs

- Lights to indicate the selected function(s)

- A switch to select all or separate crew-passenger intercom audio

- An intercom On-Off-Volume control

Now, here are a few things that will bear on how we think about this unit:

- Most audio panels are what are called “unity gain” devices. That is, they take audio in and process it, switch it, or redirect it. But if you put a volt of audio into the unit, you will get a volt of audio out of the unit. They may take an input that is only strong enough to drive one set of earphones, but the audio panel should have enough power gain (not voltage gain) to drive at least four and preferably six sets of headphones.

- If possible, the switches should be push-button, and to provide a little help at night, it would be nice if the switches were lighted (it doesn’t cost that much more). The old-fashioned toggle switch has seen its time.

- Back in the day, most aircraft came with headphone jacks and an overhead or sidedoor speaker. Speakers are a thing of the past. Not only does the strong magnetic field need extreme shielding to keep the compass from pointing directly at the speaker magnet, but almost all of us today recognize the folly of sitting in a 100+ dB noise chamber for hours on end without some sort of ear protection. Hence the almost universal acceptance of headsets when we fly. A high-powered speaker amplifier is not necessary.

- It would be really nice to provide a third com radio if it is not prohibitively expensive. Not for the aircraft band, but a lot of us fly search and rescue, or amateur radio, or marine radio, or business band radio, or children’s band (CB) radio and would like the capability of that third com (with microphone circuitry to match).

Now let’s talk about the stuff that we’d like to have:

- A lot of rumbling about how Bluetooth is the best thing since sliced bread and bottled beer. I’m not convinced, but I’m willing to at least look at it (grumble).

- Same amount of rumbling about stereo headset outputs and stereo music inputs. Again, I’m willing to at least look at it (grumble, grumble).

- A short (2 minute?) digital voice recorder to record memorable minutes, ATC instructions, comments by the crew/passengers, or any other audio that the pilot selects.

- Other stuff that I haven’t seen anywhere else—good ideas?

Having designed 10 audio panels between 1974 and 2010, I can take an educated guess that the bare-bones unit we talked about above can be put out the door for about $300, with the usual caveat that this does not include assembly labor. You get to assemble it yourself and install it yourself. How much does that save? Consider an audio panel that costs 1 AMU and close to another 1 AMU to install. Do it yourself and it looks to me like somewhere around $1700 in the bank. Even with avgas at $5 a gallon and our steeds sucking 5–7 gph, that’s about 60 flight hours at no cost to you.

Bluetooth? Maybe another $15–$20. Stereo? About the same. Voice Recorder? About the same.

So, tell you what I’m going to do. In the electronics industry we have what are called “focus groups.” These are experts in their field that designers present their ideas to and get feedback. Call it Shark Tank on steroids. I’m going to establish an online survey that you can take to give me your feedback on what you are looking for in an audio panel. I’ll reveal the results in a future column.

You can take the survey anonymously. And, if this turkey ever gets designed and built, I’ll throw all of your names into a hat and draw one name out for a freebie of all of the stuff that comes out of the survey. Until then… Stay tuned…