Last month we tackled the wobbly control stick on Kevin King’s SQ2000. This month was going to be about making an adapter to fit a new GRT Avionics panel in the space vacated by his outdated and seriously ill Blue Mountain EFIS. The GRT panel was expected to arrive in six weeks. Unfortunately, there was a slight miscommunication. Kevin thought they said six weeks, but when he checked on the delivery date, it was actually 16 weeks. D’oh!

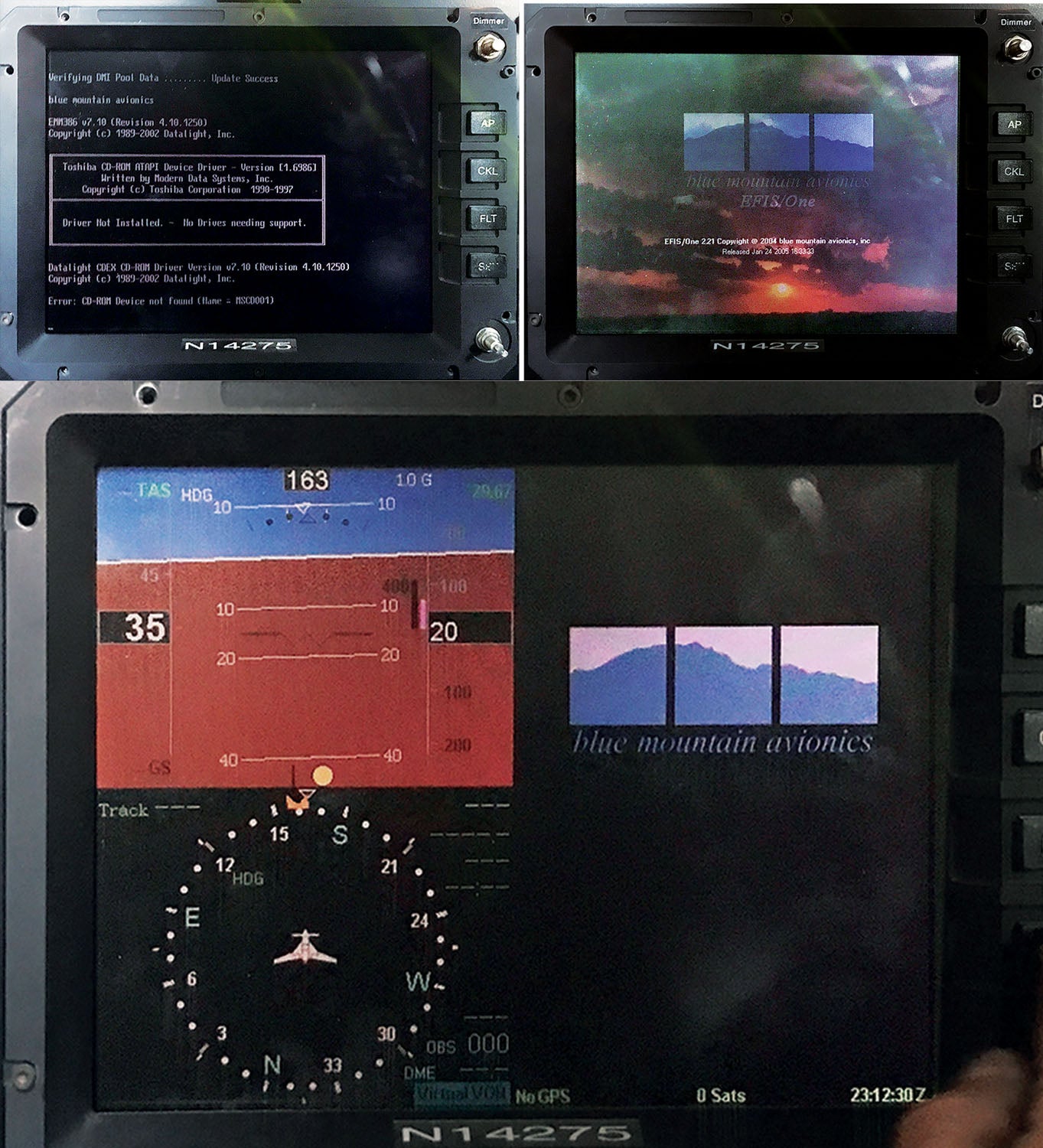

Obviously bummed over his airplane being panel-less and grounded, we pondered the improbable: Could a couple of technophobes like us get the old panel working? At least temporarily? The issue with the Blue Mountain was that the display had become severely faded. You could make out that there was something going on, but it was so “ghosted out” (a term used to describe a faded-out screen) that it was unusable. Kevin mentioned that once it started going south, the brightness or contrast adjustments had no effect.

We didn’t even consider asking an avionics shop to fix it. For all the groundbreaking features Blue Mountain offered in 2003, by today’s standards it’s obsolete. So even if one could find a shop willing to look at it (doubtful), it would not be worth what they would have to charge to take it apart and inspect it.

So we decided to crack it open ourselves and have a look. Who knows? We might get lucky and find a loose wire, a corroded connection or a burned out component. But if not, Kevin was no worse off than before.

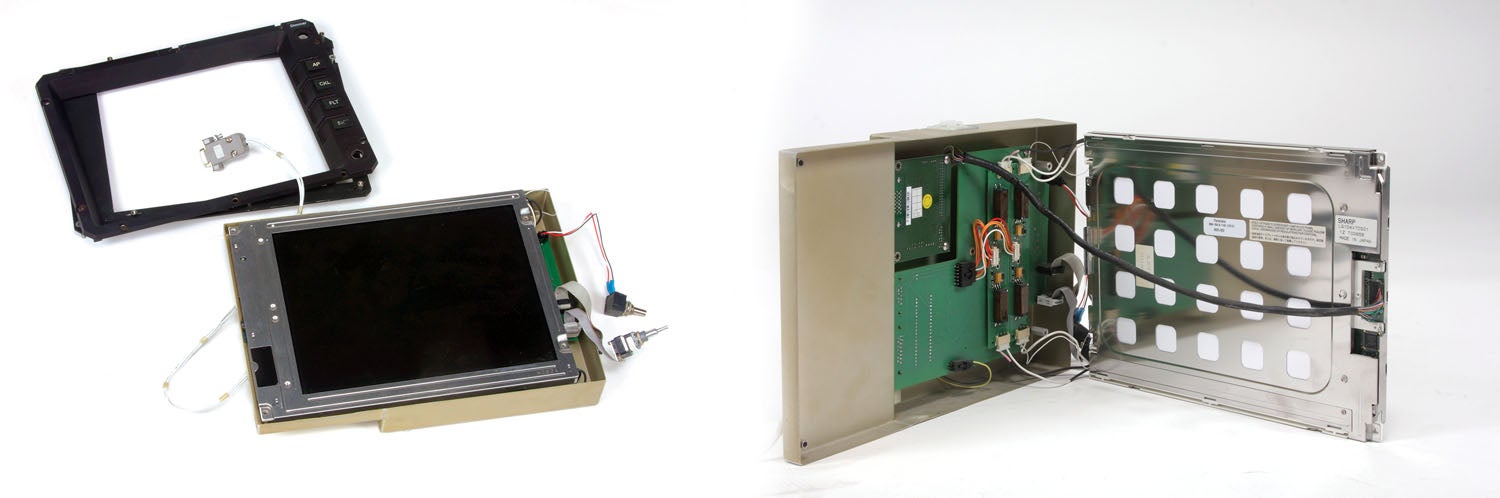

The Blue Mountain system consists of two separate components: a display assembly and a processor unit. The display assembly consists of a bezel face with four switches and two dial control pots, a liquid crystal display (LCD) screen, a circuit board and a case enclosure. The display assembly is connected to the processor unit via cable with multi-pin connectors. The processor unit is a big (about the size of two shoeboxes) and heavy metal enclosure that has a gaggle of connectors for engine monitoring, autopilot, nav/com, GPS and pitot-static systems. It is a reminder of how far electronic flight systems have come in the last 20 years: big and heavy versus compact and lightweight.

Cracking open the display assembly turned out to be easy. The bezel and dial pots were connected to the circuit board with multi-pin connectors. With the bezel off, it was simply a matter of removing four screws to separate the LCD screen from the enclosure.

All the connections between the screen and circuit board appeared to be in good order and there was no corrosion visible anywhere. A detailed inspection of the circuit board for discolored or damaged components revealed nothing.

But then there was an “aha” moment. A sticker on the back of the LCD screen identified it as a Sharp Electronics LCD model number LQ104V7DS01, an off-the-shelf item. A Google search confirmed this model was still available, and for as low as $88.

Kevin figured $88 was not too big a risk compared to what a repair shop might charge. We were banking on the fact that the problem was the screen itself and not the processor or a problem with the board in the display enclosure.

Kevin purchased the panel (with free shipping) from an eBay seller located in California, and four days later it arrived in what appeared to be factory-new packaging. All we had to do was plug in the connectors and fire it up.

Back at the hangar, we did just that. And…it worked! So, at least for the short term, Kevin can get back in the air. Although electronics repair is not a thing for either of us, fixing the Blue Mountain turned out to be a completely mechanical job. Which proves there’s no harm in looking. In the meantime, it’s time to get back in the shop and make some chips!