My customer relationship with Crow Enterprizes (their name back then) goes back 20 years to when I was building my RV-8. I was building my first real aerobatic airplane and, of course, that meant I wanted a “real” harness system with military-style rotary buckles. Some internet searching quickly pointed me to racing harnesses—the military buckles had military price tags, so they were out. The popular aerobatic harnesses at the time were all using the old reliable latch buckles. But the racing world had cool harnesses and further research showed me harnesses from a couple of manufacturers. But Crow stood out in terms of price and features. I called and told them that I wanted harnesses for an airplane and instead of hanging up on me they asked to know more—and the relationship began!

My customer relationship with Crow Enterprizes (their name back then) goes back 20 years to when I was building my RV-8. I was building my first real aerobatic airplane and, of course, that meant I wanted a “real” harness system with military-style rotary buckles. Some internet searching quickly pointed me to racing harnesses—the military buckles had military price tags, so they were out. The popular aerobatic harnesses at the time were all using the old reliable latch buckles. But the racing world had cool harnesses and further research showed me harnesses from a couple of manufacturers. But Crow stood out in terms of price and features. I called and told them that I wanted harnesses for an airplane and instead of hanging up on me they asked to know more—and the relationship began!

Beginnings

Fred Crow founded Crow Enterprizes (now going by the name of Crow Safety Gear) in 1997 when he was 62 years old. He started out in motor racing at a young age and worked for Simpson Safety for decades until he decided to strike out on his own. He had grown a significant reputation and quickly attracted customers to his new business, running the company with family (a practice continued to this day) and working out of a shop in Fullerton, California, that kept overflowing into adjacent buildings. His wife, DeEtte, was with him from the start. Their sons moved in and out of the business as their lives grew.

In 2019, son Matt (who had moved into a company doing long-haul trucking) got a call from Fred telling him that they were moving the company to Las Vegas, he needed Matt’s help and that it was happening within days. Matt reported for duty with a borrowed panel truck and made numerous trips between southern California and Las Vegas to transport the company’s machines, fixtures and stock to the new location. And just like that—within a week—Crow was back up and operating with lower costs in a fresh location.

The Aircraft Side

Crow now occupies a “rightsized” facility in North Las Vegas, with a cadre of experienced employees sewing hardware onto webbing and assembling finished harnesses for shipping. Matt showed us a large three-ring binder with all of the information he has collected on the various homebuilts for which he has provided harnesses—and said that he is always looking to expand the book when someone needs a harness for a new type—and it is clear that he enjoys the “custom” design work!

While the Crow customer base is still 80% motorsports, the 20% of the business dedicated to aviation is important to them. Because of that, Matt has for the past several years had a booth at AirVenture and many have talked with him there. But what you don’t know is that his presence is a solo act that involves him driving all the way from Vegas, towing a trailer. He doesn’t rent a house or stay in a hotel—he camps in Scholler, just like thousands of aviation fanatics—and he is still in awe of the size and scope of the AirVenture experience. So if you see him around at the big show, invite him to join your camp for dinner or breakfast—he’ll learn more about aviation and you’ll make a new friend.

Fred Crow passed away earlier in 2024, so Matt now runs the day-to-day operations along with his mother, his wife and their dedicated cadre of employees.

Building Harnesses

Crow doesn’t make hardware—they buy buckle components from a mechanical fabricator on a quarterly basis so that they always have stock on hand. The “soft goods” (webbing) comes from a manufacturer in Rhode Island that also supplies webbing to government and military contractors. Most of the webbing is nylon, but they do have special requirements for polyester (which is stiffer, less flexible and has essentially no stretch) and keep some on hand. Polyester might be used, for instance, in harnesses with ratchet straps, since the idea in those cases is to have zero stretch or give. Unless you have a special design consideration, you’ll be getting nylon when you order a Crow harness.

Hardware comes in different styles. There are two basic latch systems—a lever-latch (like airplanes used for close to a century) and the newer style rotary buckles. Matt said that most customers in the Experimental aircraft world come in looking for the rotary buckle and those who choose the lever-lock do so because it is what they are used to from their earlier flying days. But if he can get them to try a rotary, they rarely go back.

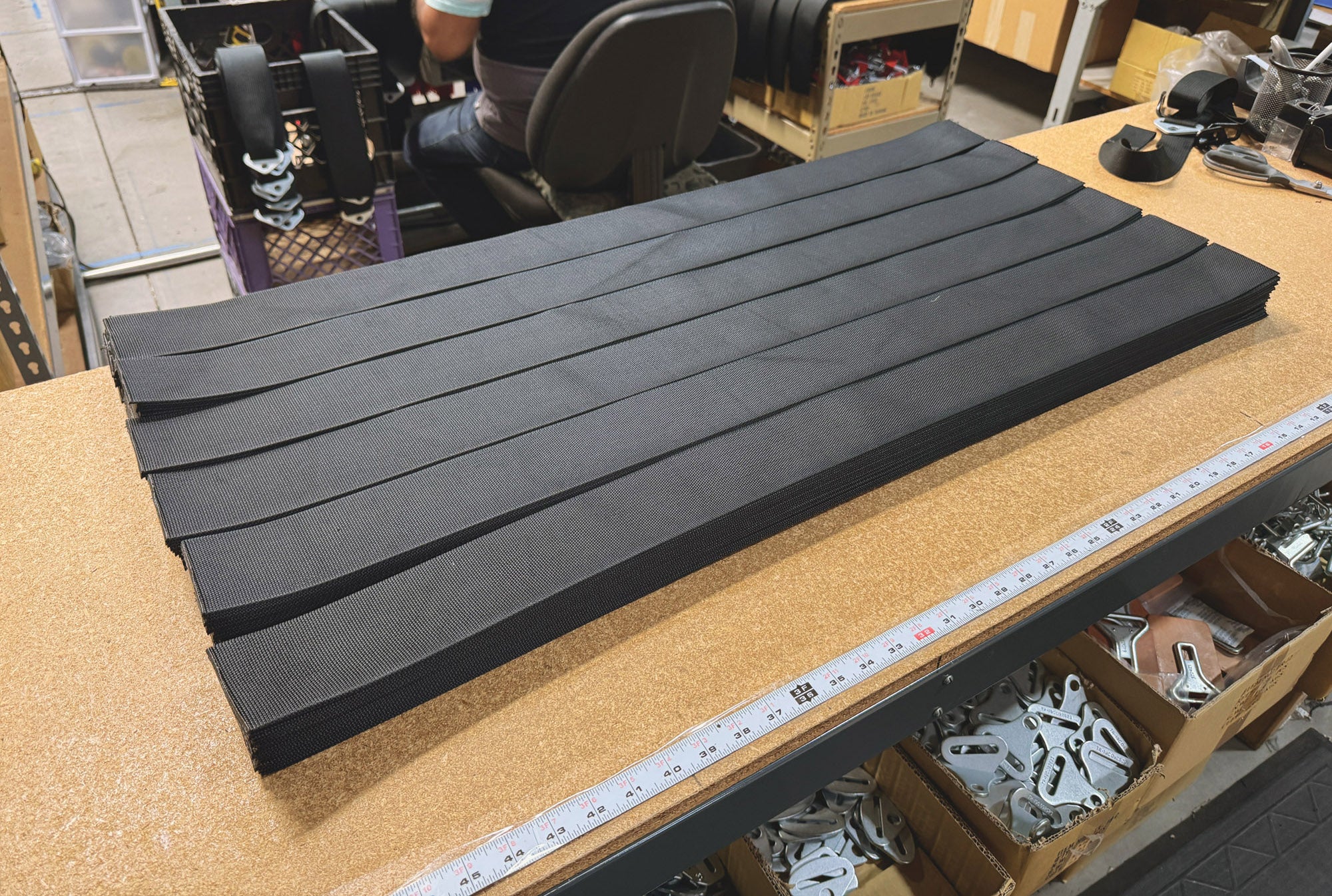

Crow harnesses are modular to the point that one group of employees just makes components—shoulder straps of various lengths, lap belts of various lengths and anti-submarine (crotch) straps of various lengths. These then go into storage until someone orders a harness, at which point an assembler pulls what he needs to put together the customer’s exact order.

Fabrication starts with the cutting of nylon webbing to length using a machine that feeds the right amount of material from a big spool, cuts it and sears the end all at once. It can spit out pieces as fast as they can be collected and stored for the sewing tables.

Buckles are sewn to the webbing using heavy-duty nylon thread in a pattern that has been proven to take the loads required by racing specifications—loads that in general far exceed those you might see in a survivable aircraft crash. The sewing patterns are stored in what Matt described as a “CNC sewing machine”—the operator inserts the webbing through the buckle, folds it over, lines it up in a frame under the sewing needle and pushes the pedal. The machine moves the frame so that the zig-zag stitching is done repeatably.

Next, the webbing/buckles get labeled. The labels are important for the automotive world, as they have a date code that determines when they have to be replaced, as required for competition use. The seamstresses can line up and stitch labels at a dizzying rate—they are really good at what they do! These same seamstresses make harness pads and sew pads onto shoulder straps as required to fill orders. Assembly is done to order and doesn’t take very long—while we were there, we saw numerous harnesses put together, folded and boxed for shipment.

Harnesses can be customized for length. Matt is happy to work with customers through multiple iterations to get things right for a new aircraft. I have personal experience with this process from my SubSonex build, with the first shoulder belts being shorter than necessary and the second ones proving just right. And as mentioned, hardware combinations can be chosen to get exactly what the customer needs. But if you have an RV, Kitfox or Sonex, you probably don’t need anything custom—Matt has already figured those airplanes out (with the help of customers) and can make what you need.

Learning About Harnesses

If you’re like most pilots, you probably don’t give seatbelts and harnesses much thought—so long as they don’t frustrate you. Aircraft harnesses have no defined life limit—you replace harnesses on condition. So what is the expected lifetime? Matt said, “I really don’t know. There are too many variables. Exposure to sun accelerates aging—but most people hangar their homebuilts. It’s really bad if you get battery acid on them. But any petroleum products are bad—gasoline, for instance. Contamination with chemicals is grounds for replacement.” I asked about things like soda and other drinks and he said, “Wash ’em off and they’d be fine.” Fortunately, Crow is now advertising a “renewal” program for aviation harnesses—send them in and they’ll replace all the webbing, reusing your hardware.

Most of the harnesses that Crow sells to aviators use 2-inch webbing—they make a lot of auto racing harnesses with 3-inch, however, and they can do aviation harnesses with 3-inch webbing. I asked Matt the pros and cons since my original Crows (in my RV-8) are 3-inch because, well, I honestly don’t remember why. Probably because I felt that forces would be spread out better. But the cons with 3-inch is that the shoulder harnesses tend to restrict arm movement if they get too wide and the wider belts trap more heat, making the pilot hotter. While I have never felt like getting rid of the 3-inch belts in my RV-8, I noted to him that all my other airplanes (that I built later) have 2-inch belts and they work just fine.

I asked Matt if he has any tips for pilots on how to treat their harnesses, and he said that one thing he always encourages folks to do is to open up their shoulder harnesses (loosen them) all the way before taking them off. Nylon tends to take a set, and if you leave them adjusted for yourself all the time, the “set” will be right in that spot—then if you change to a heavier coat or wear a parachute under the harness, it takes extra effort to loosen them up. When I asked him about what’s inside those clever rotary buckles, he said that taking them apart to find out is a really bad idea—he’s never had one apart that he got back together again—so let the magic happen and don’t ask any questions.

A Good Choice, a Good Price

Let’s be honest—almost any harness you are likely to buy from a quality supplier (or that you receive as part of your airframe kit from your kit manufacturer if the harness is included) is likely going to work for you. But this is homebuilding, where you want to have exactly what you want to have—and we have found Crow to be an excellent choice based on quality, experience and customer-oriented design and service. If they don’t list your exact model of aircraft on their website, just give them a call—they’d be happy to build exactly what you need, then add the dimensions for yet another aircraft design to their ever-expanding book!