Warbirds are expensive. Expensive to buy, expensive to restore and expensive to fly. For all that, you join a privileged cadre of pilots/owners who can walk with a particular swagger—not unearned in most cases—and you get premium parking spots at most airports and events. But for most, those expenses make owning and flying a warbird a fantasy.

Warbirds are expensive. Expensive to buy, expensive to restore and expensive to fly. For all that, you join a privileged cadre of pilots/owners who can walk with a particular swagger—not unearned in most cases—and you get premium parking spots at most airports and events. But for most, those expenses make owning and flying a warbird a fantasy.

For this reason, kits and plans for warbird replicas have been part of the homebuilding landscape for almost as long as homebuilding has been around. Varying in scale, weight and power, some mimic their progenitors better than others. What is generally true about all of them, however, is that they are homages to the classic fighters of the two world wars—Sopwith Camels and Fokker Triplanes from the first and Mustangs and Spitfires from the second. Success breeds imitation, I guess. But there were many different successful designs to come out of those conflicts that, while less famous, still have their place in the pantheon of warbird replicas.

ScaleBirds, a newcomer to the kit manufacturing scene, chose to start their line of replica fighters with one of the first all-metal U.S. military pursuit ships of WW-II—the P-36. Its classic lines show the roots of what would become the mightiest fighter fleet in the war—single-seat and nimble, a way to carry and point guns at targets. Why did they start with the P-36? Why not? They liked it and growing the design it can easily become a P-40, which is just what happened in the war. And, as they put it, “there are lots of Mustangs out there.”

The P-36 has graced the grounds at AirVenture for a number of years as a static display, but this year it has come into its own as a flying machine. I was invited to New England for a chance to fly this fun little fighter to check it out for ourselves. The fall colors were just beginning to appear as we lifted off of the seaside runway in Rhode Island, intent on defending our shores from the invasion fleets of islanders tracking back and forth from Block Island and Martha’s Vineyard. I won’t claim any kills, but the experience was still one for the logbooks!

ScaleBirds: What’s Old Is New

ScaleBirds and something called the LiteFighter idea are the brainchild of Sam and Scott Watrous, a father-son team of designers who have assembled a team of engineers and fabricators that helped to produce the prototype P-36. Everything they did was with a focus on a producible kit. This is an important concept because it is one thing to make a flying airplane, an entirely different thing to turn that airplane into a kit later on. If you design the prototype with kitting in mind, you are several steps ahead of the game.

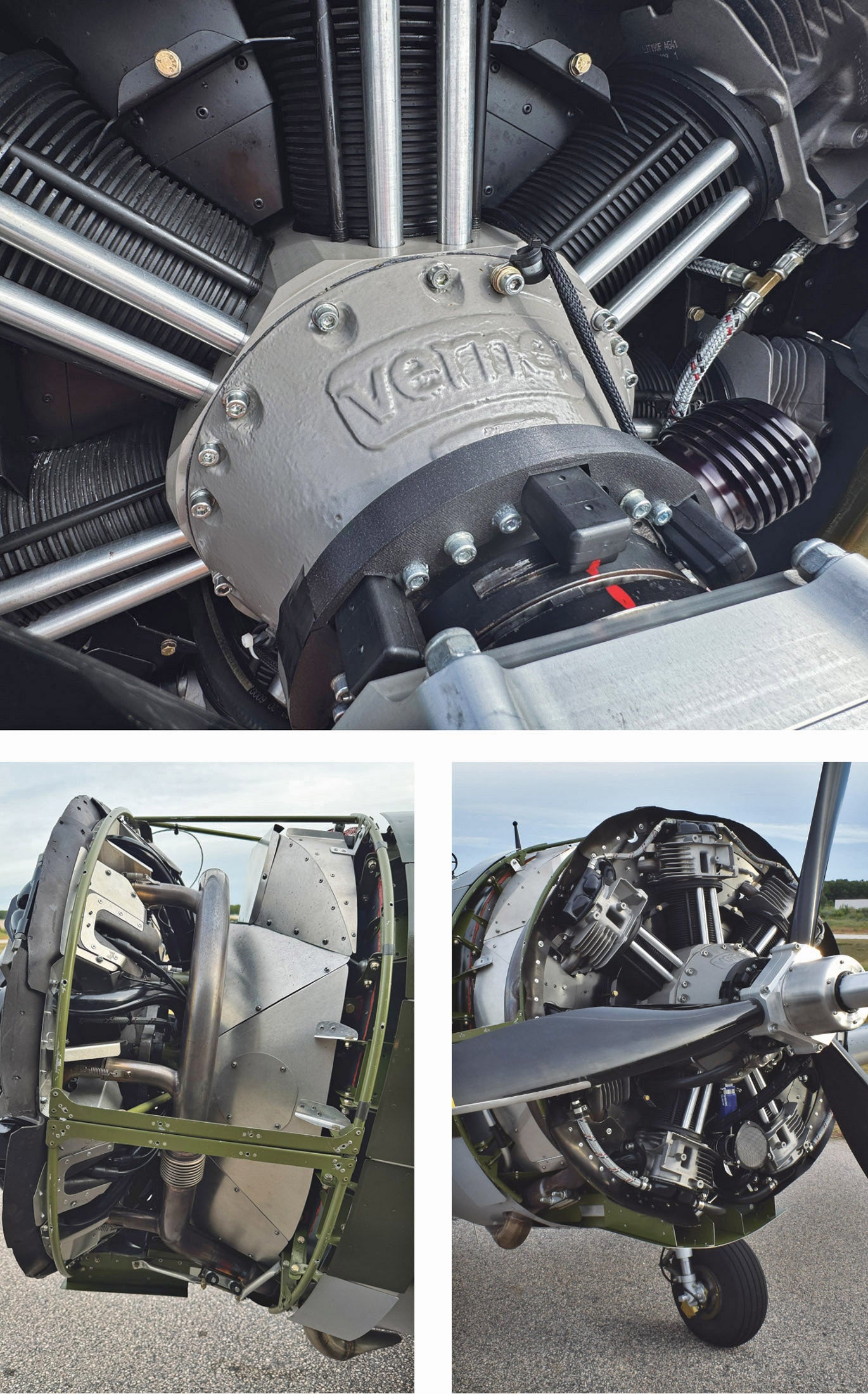

One of the things that I found remarkable about the P-36 is that for an initial design, it worked amazingly well right out of the box (so to speak). The airplane was licensed a couple of years ago and has about 100 hours on it—and it is very mature at this point. There has not been a lot of work done to change anything since it first flew—the most significant that I uncovered was the addition of the split flaps. The engine has had some revisions that came from Verner to increase reliability, but this remarkably successful airplane came out of a new company.

The concept of the LiteFighter is to produce scale flying airplanes that look like their predecessors but are affordable and flyable by an average builder/pilot. That concept is not entirely new—there have been a number of companies over the years with the same goal, notably the WW-I replicas by Airdrome Aeroplanes. Those airplanes shared similar structure and design concepts while featuring different “skins” to replicate specific airplanes of the period. The ScaleBirds folks are doing the same thing here, but with WW-II replicas that fit into the current LSA rules.

The ScaleBirds operation is not large, but it has a lot of heart—and the heart is a workshop populated with CNC lathes, mills and router tables to produce parts. There are currently five “beta builders” who have received tail parts for their P-36/P-40 projects and these should be followed soon by fuselage parts. As of this time, complete kits are not yet available, but the company is working at a steady pace to get there.

The current plan for the kit involves the traditional structure of subkits—empennage, fuselage, wing, firewall-forward and finishing—that will be released in the near future. Prices are undetermined. While the prototype aircraft is fairly mature, the kits and kit contents are still being defined, so costs are still unknown. For scale, the Verner engine is in the neighborhood of $22,000 (plus or minus, depending on configuration and options).

Two Fighters in One!

The ScaleBirds team did a clever thing in choosing their first LiteFighter—they actually created two kits in one design. Because the Curtiss P-36 grew into the P-40, it is an easy thing to create a single set of structural parts to allow it to be built either way—as a P-36 (with the Verner radial) or as a P-40 (with an inline or opposed engine under a sleek cowl). There have been other homebuilt designs created with a similar concept, but they are mostly plansbuilt airplanes that few will tackle these days. You can start a ScaleBirds project without deciding how you want to finish it—and make your choice based on how you feel when you get serious about the firewall-forward options—engine mount and cowl, primarily.

The airplane uses a combination of building techniques. The control surface frames are aluminum frames—some tubes, some stamped ribs—with pulled-rivet construction. You then cover them with fabric—the factory used Airtex for its simplicity. It was common for WW-II fighters to have aluminum primary structure and fabric-covered controls. The commonality of control surfaces between the P-36 and P-40 allows you to start right away and make decisions later.

The fuselage is not (currently) a monocoque structure—it has an internal tube-and-gusset frame created with pulled rivets, with a sheet metal structure creating the external shape. This again allows them to build a variety of different aircraft using the same basic “loaded” structure. There was some discussion of this being changed to a more traditional monocoque design, but what they have works just fine and will probably go into the initial kits. All of the structures were statically load tested.

The wing uses a built-up main spar and is of traditional pulled-rivet aluminum construction. When you are designing parts using CAD and cutting patterns to make form blocks using a CNC machine, it isn’t that much harder to build a tapered wing, so in the interest of authenticity, that is what they are doing. One item of note. There are plans to shorten the ailerons by about 6 inches, making them closer to scale, and lengthening the flaps into the space for future iterations. This should give better flap authority and tame the very sensitive ailerons a bit as well.

The landing gear in the flying prototype is fixed. It looks a lot like it is retractable because it is designed to go that way in future aircraft. It looks perfect on the ground the way it is, but a little odd in the air with the gear down—so retracts would be nice. However, retracts come with the price of complexity as well as taking the aircraft out of the LSA category.

There are some fiberglass parts (empennage fairing and some parts of the wing fairings) as well as a number of small 3D-printed parts (such as the gun barrel housings and navigation lights) that add to the authentic look without requiring authentic expensive metal parts. The creative team is also using 3D printing for rapid prototyping of parts as well as foam forms for new test parts—it’s a whole new world in aircraft design!

Cockpit Checkout

The cockpit of the ScaleBirds P-36 is roomy for a single-seater, making me wonder at the wizardry used in scaling the aircraft. I have flown full-sized warbirds with less room for the pilot, so clearly some accommodations were made to fit a modern adult human. While the cockpit rails are a little closer together than the longerons in an RV-3 or Panther, the width of the cockpit below them seems to be quite generous.

The cockpit is simple and the control arrangement is straightforward. Sweeping from left to right, you’ll find a flap switch just behind the throttle, the throttle quadrant itself having only a single lever—no mixture control. Ahead of that, on the main panel, is a “choke” push/pull knob (actually an enrichment control) used for starting. Tucked up under the left side glareshield is a flap indicator. The main panel has four steam gauges. A row of small modern round gauges for engine and fuel monitoring is below that, with a 2¼-inch MGL radio head and miniature transponder.

The seat in the prototype is tan canvas cloth, much as you’d expect from a military airplane of the era, and the military latch style five-point harness plays its part in continuing the illusion that you have climbed back into history as you slip into the cockpit. The canopy is narrower than a modern bubble but the visibility is good once you get used to looking around the frames that form the structure. Overall, it was easy to slip into the illusion of playing an early-war fighter pilot in this little machine, which is really what you’re after if you go to build or fly one in the first place!

Let’s Go!

Strap in, get your kneeboard and charts ready (there is no moving map or EFIS here) and let’s get it started. That’s simple enough. Fuel on fullest tank, master on, ignition switch on and ignition switches both on. Throttle to idle, pull the choke knob and hit the starter. The wonderful little Verner radial cranks and fires up. Play with the choke a little to get it to keep running and after a few seconds, you can release that and the engine will be idling on its own. It’s not silky-smooth like a Rotax, or even moderately smooth like a Lycoming—it lopes along like a typical radial (or Harley), but you’ll quickly feel comfortable.

“Oh yeah” said Watrous…“it’s got a few rpm bands where it shakes pretty good!” “Is it hurting anything in those bands, do I need to avoid them?” I asked. “Not really,” he said, so I didn’t bother writing them down. I just found another place to put the throttle if I didn’t like what I felt throughout the flight, and the Verner and I lived happily together.

The airplane taxied just like any taildragger but you’re going to relearn the art of S-turning. There’s no looking over this little beastie and the blunt front end of the radial means you have to turn pretty wide to see around it. The Westerly State Airport in western Rhode Island, where ScaleBirds flight tests, had taxiway lights up on sticks that looked like they might snag a wingtip, so I carefully wended my way down to the runway threshold, turning between them to make sure nothing had pulled out in front of me. Steering is excellent, either with the full-swivel steerable tailwheel or the brakes. Take your pick and use both as required.

The takeoff checklist is complete once you double-check those flaps. They are split flaps, so when you look out of the cockpit, you don’t see them—up or down looks the same! The airplane can be flown with the canopy in any position from full closed to full open, so if you forget to latch it there won’t be a problem—I only flew with it closed, so can’t speak to how frenetic the cockpit might be with it slid back.

Ready to Fly?

Stick forward, add power and you’re off. I expected maybe a little more drama with the high nose and short airplane but it tracked straight ahead. The tail came up with excellent rudder control. This is not an overpowered airplane, of course, so the acceleration wasn’t blistering, but we eventually reached flying speed (in a few hundred feet) and a slight tug got the mains to break ground.

The first impression was “light.” The controls are low effort in all three axes. Right off the bat, however, take a look at the ball: This airplane wants lots of right rudder in the climb, which is not so unusual. It also wants lots of right rudder in level flight! Watrous later told me that they are planning on shifting the leading edge of the vertical stab off center to trim it out.

Pitch felt about right for an airplane this size—close to naturally stable but still positive. Roll is very sensitive right now, very light and neutrally stable. But it will quickly fall off to the left or right (it is not picky about which way it goes) if you put your head down to write a note. My suggestion after flying it is that as delightfully quick as it is right now in roll, I’d probably tone that down just a little to match the pitch response and make the airplane more harmonious.

The speeds I saw on the flights are to be taken with a grain of salt, since the system has yet to be calibrated with any precision. In our air-to-air session, I saw a speed difference in cruise of about 12 knots (the P-36 showed fast, indicating 95 knots while the camera ship was doing 83 knots). The primary ASI ring is also in mph, which is actually fairly authentic for the WW-II era, so we’ll talk that way. Doing a very rough recalibration to what we think the speeds are, best climb was at about 75 mph, approach about the same and top speed is probably right around 118. But those are all contingent on a recalibration—the static ports are usually the suspects for inaccurate speed with any new aircraft design and that is probably true here as well. I saw indicated stall speeds of about 68 mph clean, which sounds too high—let’s peg it closer to 60 mph until they get better numbers. Stall with flaps deployed wasn’t much lower, as is typical with split flaps.

So, let’s talk about slow flight. Basically, the airplane was well behaved and showed no bad characteristics in the stall—it broke gently with just a little drop of the right wing. However, that might be because of the right rudder required for level flight and not taking it out at the break. Rudder control was excellent during near-stall, stall and recovery—the airplane was honest in the slow-flight regime. With the flaps out, the airplane’s stall doesn’t change much—the effect of the split flap is to add drag and pitch the nose down a bit. Watrous said that they added them after the first couple of flights because, in his words, “I couldn’t get the darn thing to land!” He was getting a steep approach with the nose high and it wasn’t very comfortable, I suspect. The flaps make it more normal.

It’s worth remembering that despite the fighter-plane looks, this is not a high-performance airplane—it is essentially a Light Sport, with about 100 hp. So while it handles very nicely, you can’t just haul back and expect several thousand feet per minute of climb. That’s not so much a real limitation but it is something to remember before you get your nose pointed at the sky looking for that Zero. Enjoy it, just in moderation. Initial climb is about 800 fpm from sea level, which isn’t bad with that big round engine in front.

Formation flying is a real test of handling qualities and I launched our second flight to catch up with a Bearhawk camera ship to check that out. In short, the airplane was a dream in formation, despite not having a constant-speed prop, which really helps in making quick speed changes. The P-36 was incredibly easy to place precisely in the fore/aft position. I personally chalk that up to the drag of the round engine, which does the same job as a constant-speed prop. Add a little power, the airplane walks forward, take a little off and it stops, no overshoot. That’s about as easy as it gets. Up and down was quick, as was left and right, using the rudder to skid into position. I fly a lot of different airplanes in formation and most of those I do after about 30 minutes (or less) to get used to it. This was very close to the easiest I have done with little time in type.

Ya Gotta Land It!

Having done some slow flight and a stall or two, I knew that the airplane could develop a pretty good sink rate, so I decided to try first for a wheel landing with the flaps out at the recommended 30°. With the uncalibrated ASI, I kept the speed up more than usual. I used some power to keep it on the front side of the power curve and it still felt like pulling back on the throttle gave me a pretty good sink rate, so I took advantage of the long runway and just set up a nice slow descent to a tail-high touchdown. I got a nice squeaker, pulled the power off entirely and let the tail settle. Control was good on this calm-wind day either with the tail up or the tailwheel on the ground and I was able to brake to a stop about 2000 feet down the runway, having probably floated down at least a thousand of those feet.

I was curious how it would feel (and what the sight picture would be) in a three-pointer, so I taxied back and went around the pattern one more time. This time, I pulled it back a bit more and was likely on the back side of the power curve as I let it settle with the tail much lower. I won’t claim a three-point squeaker, but it was close—and probably a little less comfortable because of that big noise up front making it a little trickier to tell exactly how I was pointing. But with no measurable crosswind, I stayed on the centerline and was happy with the result.

Trim is your friend and so are the flaps. I didn’t try a no-flap landing in the limited time I had, but I took Sam’s word for it that the flaps keep that nose lower for a better sight picture. The only tricky thing about the airplane is the fact that the first time you fly it, you’ll be solo—so finding a good example of a draggy taildragger with two seats to get checked out in would be a good idea. It might be the excuse you need to go get a little biplane time!

A Fighter in Every Hangar

The P-36 from ScaleBirds is not intended to be more than it is—a very fun little airplane that looks interesting and can give you a touch of what it must have been like to look out of the cockpit of a WW-II era fighter. The “birdcage” canopy, the steam gauges and the big round nose all contribute to that sense of nostalgia. And it does a great job at a price that should be far below some of the other replica kits out there that we have flown and enjoyed. Certainly, if you want to pretend you’re flying a Mustang, you aren’t going to get the same feeling with a P-36. But you can build this airplane as either P-36 or as a P-40—and the AVG Flying Tigers were a pretty aggressive and successful group of fighter pilots, so that’s nothing to sneeze at.

The Verner engine is definitely a newcomer to the GA world here in the U.S., but so far it has proven to be a fairly reliable engine with a few teething problems having to do with leaded fuel—fly it on mogas and those issues should go away. It has no history of massive failures and that’s a great thing—a little loss of power from a sticky valve is far better than a thrown rod. Or choose the P-40 option they are working on. I kept thinking how this airplane might fly with a Rotax 916 iS out on an extended nose, with that big mouth scoop and a shark’s mouth painted on. You’d certainly attract some attention as you taxied into the local pancake breakfast! Even in the P-36 configuration, the airplane is a good enough replica that many an aficionado could be fooled until you get out and they realize that “hey…that’s smaller than I thought it should be!”

The Warbird Division at AirVenture probably won’t let you park along with the rest of their birds (or maybe they might—you never know…they might want a mascot!), but this airplane will certainly turn some heads when parked in the homebuilt area in Oshkosh in July. And when you’re not taking it to the show, you have an inexpensive, fun airplane to knock around your local skies.

Photos: Paul Dye, Ashley Anglisano, Larry Anglisano.

A P-40 with Rotax installation sure would be interesting!