It can happen to anyone, but maybe more so with age. We don’t, or can’t, get up as much. Health issues arise. Other interests consume our energy. Maybe it’s not as exciting anymore or the effort to maintain the relationship becomes too much. The longer we remain inactive, the longer we remain inactive. Inertia, you see, works both ways. However, when the day does come to restore the spark—a day of excitement and apprehension—it should be done thoughtfully. Engines, you see, need frequent activity. When they sit, they corrode.

I’ve been parking engines for Wisconsin’s long, salty winters for decades. When I know a vehicle will sit unused—I mention, again, with great pain, Wisconsin’s long winters and salty streets—I take steps to preserve its engine. But hobby vehicles can go unused, often without warning, for long periods simply…because. What is a “long” period? RAM Aircraft states, “If your airplane is not flown every seven days…every source we found agrees that your airplane is, at best, in ‘flyable storage.’” Translated: The engine is corroding. How long does it take for engine corrosion to begin? Lycoming says in as little as two days or up to “several weeks.” Think on that while I grab a snack.

93 Words on TBO

Many think of TBO as a measure of an engine’s reliability and remaining life, but an airplane that’s seldom flown will never reach TBO and frequent periods of unprotected dormancy speed the engine’s deterioration further. Per Lycoming, “We have firm evidence that engines not flown frequently may not achieve the standard expected overhaul life. Engines that are flown occasionally deteriorate much more rapidly than those that fly consistently.” The take-away from this column should be that damage is done when an engine sits. These steps can only minimize further damage on start-up.

You’re Doing It Wrong

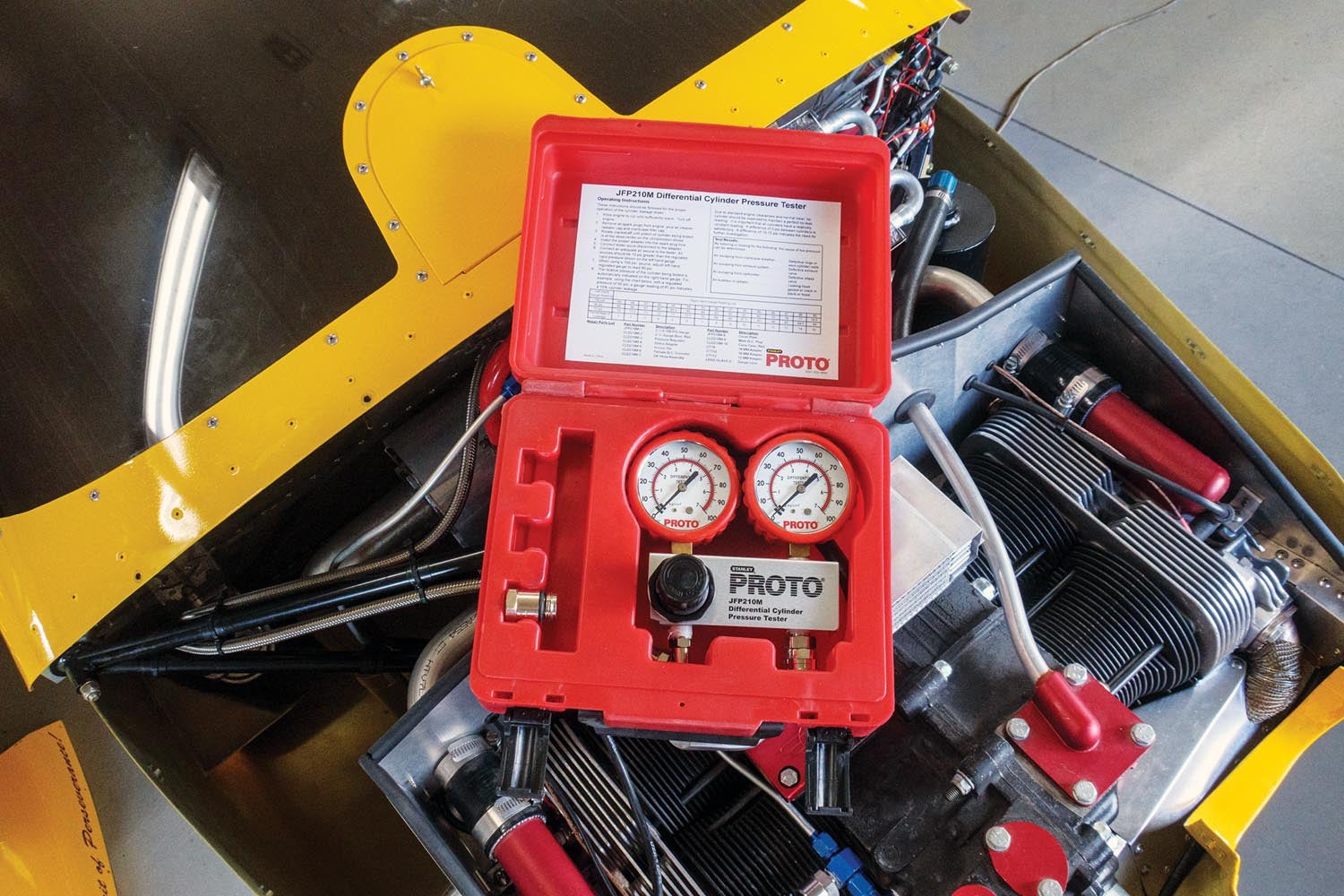

99.5% of the time a long dormant—let’s say six weeks or more, less in humid and salt-air climates—engine is jolted back to life without regard for its needs. In extreme cases the effort includes a battery charger set to Jump Start and a can of ether. Ouch. If it starts we smile, thinking all is well, unaware of the damage done and the abrasive particles circulating in the engine. There’s a better way. Court the engine. Tease it back to life. Treat it to new oil, maybe plugs, a leak-down test and the promise you’ll never ignore it again.

I’ve based this column on common sense, my personal experience and information collected from a variety of aircraft engine manufacturers. If your engine is of the certified flavor, consult its manufacturer for guidance on bringing it back to life (most of the published information I found was for proactively preserving an engine). In the absence of a manufacturer’s specific guidance, these steps, meant to minimize additional damage when you start the engine, are better than the “turn the key and pretend everything is fine” approach.

Courting Combustion

Don’t touch the prop! I know it’s tempting, but don’t. That’s too aggressive. When you turn the prop, dry, corroded parts grind against each other and the oxidized particles bust free to find other areas to damage. Your first step is to disconnect the battery’s ground cable and attach a battery tender. Not a charger, a tender. And with that I’ll number the remaining steps because technical writing habits die hard and numbered steps are easy to follow, less wordy.

2. Turn the fuel shut-off valve off, close the mixture and turn the mags off. (That’s three steps but, whatever.)

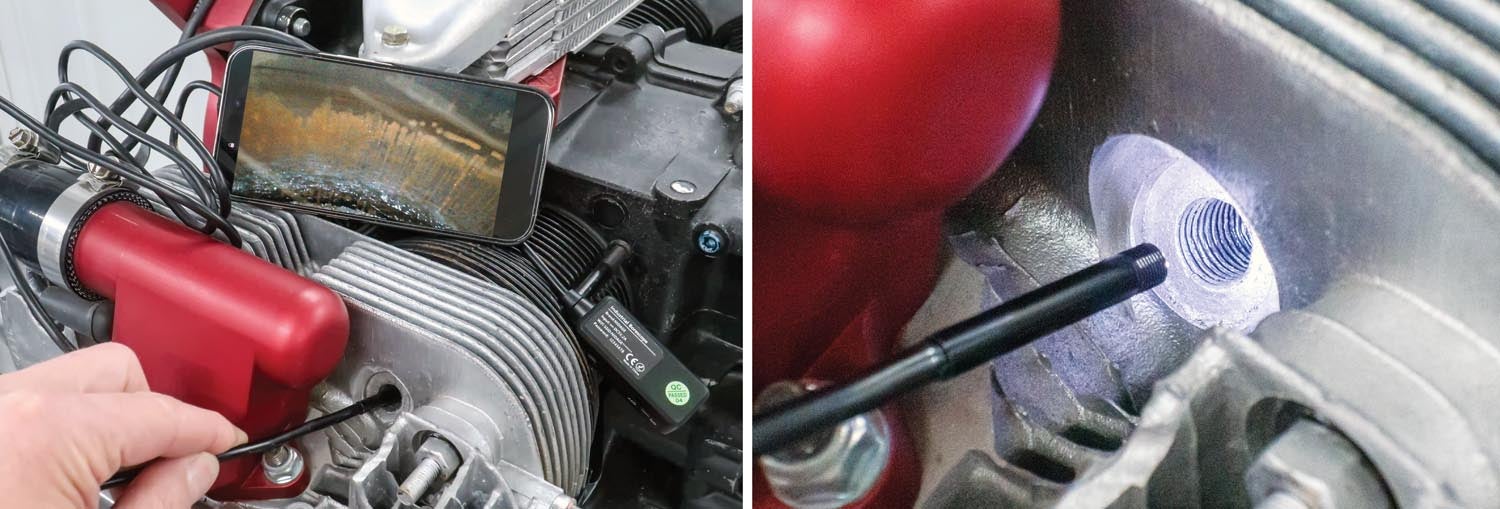

3. Remove the upper spark plug from each cylinder. This provides an opening to oil each cylinder and relieves compression when the time comes to turn the prop (step 6).

4. Spray oil in the cylinders. What kind of oil? If it were me (and who am I to tell you what to use in your engine?) I’d use STA-BIL Fogging Oil. It’s meant to protect engines as a proactive storage step, it’s an aerosol and it penetrates. It stands to reason it will lubricate your corroding cylinders and piston rings. However, a piston at the top of the compression or exhaust stroke hides most of the cylinder wall from your lubrication effort. Therefore, after the oil has been in the cylinders awhile, we’ll turn the prop to reposition the cylinders. But not now.

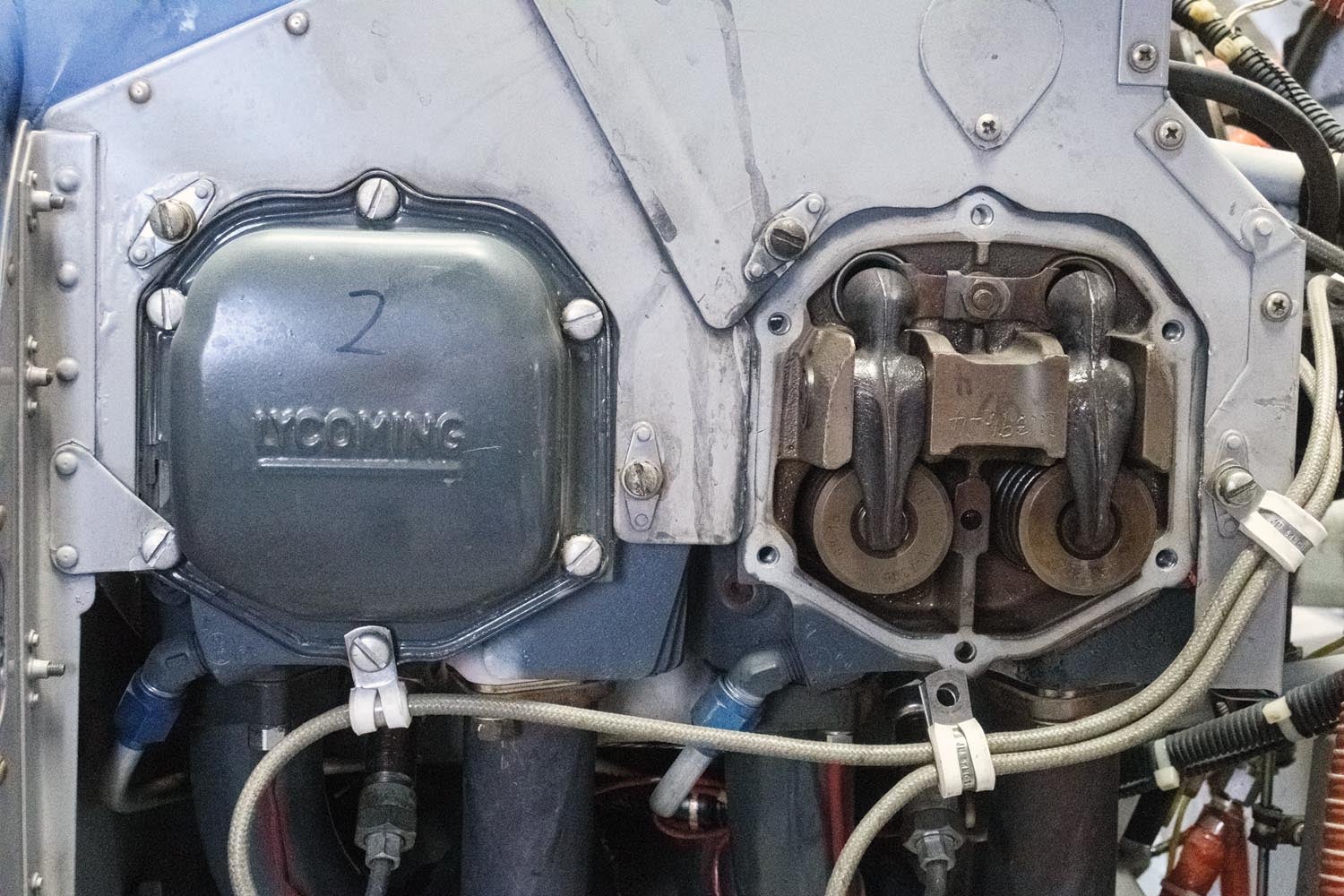

5. Remove the valve covers and brush clean motor oil on the exposed parts of the valve train. Replace the valve covers, maybe with new gaskets.

Before we move on, let me remind you that the innards of your engine are also corroding. In many engines the cam and cam followers are lubricated by oil splashing around inside the case. When the engine is shut off the oil drips off. What doesn’t drip off, evaporates. Those parts don’t see lubrication again until the crank starts thrashing the oil.

6. After the oil has had a chance to penetrate and lubricate the rings, rotate the prop by hand only enough to reposition the cylinders and expose the previously hidden cylinder walls. A wood dowel placed in a cylinder near the top of its stroke will help to determine when that cylinder is near the bottom of its stroke.

7. Spray oil in each cylinder to lubricate the newly exposed portion of the cylinder walls.

8. Preheat the oil in the sump until it is thin and runs out quickly and fully. Do not run the engine. The old oil, which has absorbed moisture and pollutants and has maybe turned to sludge, doesn’t need to be circulated further.

9. Gather what you need to change the oil. Warm up the new oil as well, to thin it out.

10. Drain the oil from the engine and replace it with new. Leave the oil filter in place (for now).

11. If the battery tender indicates your battery is healthy, disconnect it and reconnect the battery’s ground wire. If the tender couldn’t revive the battery, treat your love to a new battery.

12. With the fuel and ignition off and the upper spark plugs still removed, turn the engine over with the starter, stopping when oil pressure is indicated or before the starter overheats. (Not all engines will register oil pressure by operating the starter; use your judgment.) With the plugs removed and the oil warmed up there is less stress on the starter, the piston rings, the cylinder walls and the other bits that are starved for oil. The warm, thin oil is circulating even if pressure doesn’t register and, hopefully, some oil is reaching the parts that rely on splash lubrication.

13. Drain the oil while the damaging particles that didn’t get filtered are still suspended in the warm oil.

14. Replace the oil filter. If you want to know what parts suffered the most from the engine’s dormancy, send the oil filter out for analysis.

15. Add new oil.

16. Reinstall or replace the spark plugs. Proactively installing new plugs may be prudent.

Now you are ready to start the engine. Maybe. Depending on the length and conditions of the airplane’s dormancy you probably have other issues to deal with like bad fuel, corroded electrical connections, corroded fuel tanks, dry hoses and squatting critters.

It’s more fun and ultimately less expensive to fly than to let an airplane sit. The outflow of fuel and oil dollars is less than the cost of an engine rebuild. The cost of the engine (dollars that have already left your pocket or are doing so on monthly installments) is less when amortized over 1500 hours than 150 hours. Practice this phrase until it comes naturally: “Honey, would you like to go flying?”

Yep

Hmmm….

I agree with most everything in your article, but…

Not sure about using the starter to spin the engine with the plugs removed. I’ve read that can cause a problem with impulse-coupled mags, and possibly lead to broken gear teeth. I think pulling the prop through by hand for a few minutes is safe, and should provide some oil pressure…

Hi Peter,

Thank you for reading and contributing that valuable comment. The Experimental world in which we dabble can include any conceivable engine choice. Each owner should contact their engine’s manufacturer for guidance specific to returning a long-dormant back to service. As to your specific comment, I don’t claim to be an expert in engines with impulse mags, but often an engine manufacturer will have instructions specific to putting a new engine in service. If those instructions include removing plugs and turning the engine over with the starter to eject preservative oil from each cylinder, it should be safe to do so as outlined in my column.

Thank you again for this valuable comment. We writers have neither the full-spectrum knowledge nor the word budget to cover a topic in full.

An excellent article. But an ounce of prevention is worthwhile. An engine protected by a good dehydrator won’t rust. I know this from experience. Oil that has been used for even a few hours has been subjected to water vapor that is a byproduct of combustion of avgas. Since there are also sulphur byproducts, oil becomes contaminated with sulphuric acid. Keeping the air inside the engine well below the dew point at all times is very effective. The idea that frequent flying will prevent this is a misconception. Yes, if you keep oil on the parts then they will not rust. But the oil drains off quickly. Meanwhile, every time the engine is operated, new moisture as created and some is absorbed into the oil

Hi Howard,

YES! Prevention should be job one, but often our engines sit longer than anticipated for reasons outlined in my column. Keeping moisture out of the engine in the first place is a great place to start. Your comment jumped ahead to another column I’m writing.

Ok, I’ve always heard that you should fly at least once a week. But I think for the average pilot that is impractical. And running it on the ground does no good. The reasons I think are, loading the piston rings and getting oil temp up to burn impurities out. If you accelerate occasionally it will load the rings. And if you run long enough to get oil temp up, that should suffice. But, you need to watch your CHT’s. Don’t overheat it.

I have been a marine tech in Florida for 40 yrs. where boats will sit for 6 months. without use. And cars too. We never worried about the corrosion. Well yes, in the old days we would fog the engine for non use. But you can’t fog modern engines due to the design of the intake manifold. We worry more about the fuel system then the cylinders now.

So why is it so important on aircraft engines. Is it just because it’s flies?