Lucky stiff that I am, I actually got the plane started without much trouble and trundled up to the wide spot in the taxiway. Our county-operated flying place has taxiways and auto roads only slightly less intertwined than 16th-century Italian politics, and as sort of a time-out in the middle of it all, there’s a nice, wide spot to turn off into.

It’s not the sort of place I’d picnic in, but it is sometimes nice to sit there and let the three-blade blow some cool air through what’s left of my hair before donning leather hat and David Clark head clamp.

Some people don’t use the turnout, preferring to take their airplane from a cold, dark hangar to the hell-fury of takeoff with the same annoyed haste used to beat a dog. Myself? Although chronically late to wherever I need to be next, I always take a breather in the wide spot and let all that sticky 50 weight in the sump warm into something more akin to a lubricant. It’s a habit I got into after watching the mechanical oil pressure gauge slide up and down on my olde English race car years ago. It too had 50 weight in the crankcase, and on cool mornings the oil pressure would spike to 80 psi on engine start, then slide up and down in curiously long and weirdly non-linear sweeps and lurches as the oil would air-lock somewhere in the engine, then break through the impasse only to lock up again somewhere else. It was a real education in how poorly cold, thick oil (barely) flows, and one of many reasons that engine had an 8-hour TBO. Revving it a couple thousand rpm over redline for a half hour at full throttle had something to do with that, too, I’m sure.

But on this day temperatures were moderate, and there was no danger the Lycoming’s oil pump was mimicking a sixth grader sucking on a milkshake. As the engine warmed I went through CIGAR minus the R, then put on my hat-and-headset combination and taxied to the runway for the run-up. Finally set to aviate, I keyed the mic and hmmm, it sounded sort of dead. I tried again, and yeah, the familiar hiss and clicks were absent. I thought the frequency had been a little quiet. The avionics power was on, the radio lit up…let’s try the AWOS. Nothing. “This might be real,” crossed my mind. Okay, I’ll key the mic five times and watch the runway lights come on. Of course they didn’t.

You mean to tell me this 30-year-old sun-bleached KX-155 with the plastic curling off its displays, the one that looks like it’s mainly traveled in a saltwater canoe has…quit? How rude.

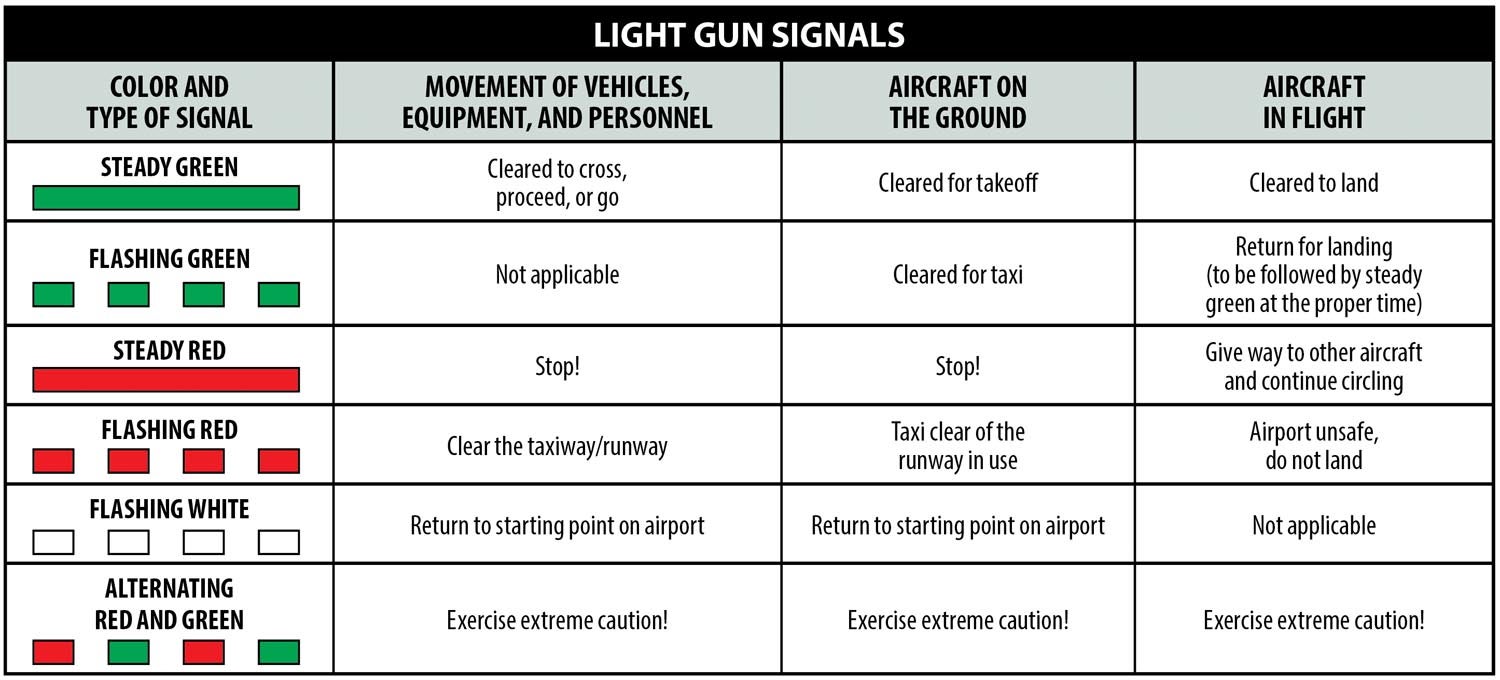

So, the non-speaking radio went away in the brown truck, and I suddenly had a mute Starduster. Trouble is, I also had a couple places to go, and those places had control towers. Now, I’m not so punchy to have forgotten light signals are still a thing, but like the rest of us, I’ve never been able to remember what all those flashing and steady beams signify 4 seconds after consulting the little chart found in those earnest little handbooks. And just how do you blunder gracefully into the traffic pattern unannounced? Guess I was going to have to study a little.

Of course my first thought was to carry a cheat sheet, but in an open cockpit that’s as practical as a pet hummingbird. But I printed one out anyway and tried to find a place for it in the blue velour palace without success. Funny thing was, as I spent time with the light gun chart and kept wishing my memory went past “3,” the signals started to make more sense.

The trick was to think like the guy in the tower, as if I had to tell a plane what I wanted it to do. I then realized there was a hierarchy between steady and flashing lights. Flashing is the more urgent, and steady lights are more procedural as it were. And you can’t just use steady green or red all the time as there are typically a couple of steps for moving planes from point A to point B. On a takeoff, for example, if you give a steady green to a plane ready to taxi from the transient ramp, you just told the guy he is cleared to take off, so that isn’t going to work. Oh, so that’s why they have a flashing green. That makes sense.

Once again, understanding the why made remembering the what possible.

After sufficient self-flagellation memorizing light signals, I felt ready to try them on purpose in the real world. It didn’t take much imagination to see a phone call to the tower prior to setting out would be a good thing, but those numbers are apparently top secret, so going through the airport manager’s office was typically required. If already on site and wanting to depart, then using a handheld or another airplane’s radio to negotiate a starting time and place with the ground controller worked like a charm. After all, the folks in the tower weren’t expecting to use the light gun, either.

To my great relief all went well, and in most ways I came to prefer light signals over making radio speak. You never stumble over your words, that’s for sure. Forced to reduce communication to a handful of signals, I had to put myself in the controller’s place. That amplified my situation awareness and gave me an unexpected better idea of what was happening and what would likely happen next. That’s because you tend to look around to see why you’re getting a steady red light when you’re ready for takeoff. Must be someone coming in to land.

Sometimes the poor controller has to hold that red light a long time, and then you notice just how focused the beam is. I was close to a mile away from the tower watching the red light, and after a while it started to dim, then come back strongly, then seemingly blink on and off—I wondered for a second if it had turned into a flashing red—before I realized the controller’s arm was getting tired or he was talking on the radio with the other hand and moving around. But I was definitely engaged with the controller. I could see how an airport, even a pretty busy one, could operate on light signals alone. It would take better piloting, but that would be a great thing.

Perhaps one reason I took to light signals was I was used to signal flags while driving in road races. There the only communication is by flaggers stationed around the track, and they have a good array of flags and seemingly endless little tricks for adding nuance to the textbook definitions of what an alternating red and yellow striped flag means, for example. Unlike the tower controller, the flagger often has the advantage of proximity and can use body English and the like to add urgency or content to his main signal.

Unexpectedly, I found light signals gave me more appreciation for procedure. There are only so many things a controller can tell you with a light gun, so being in the right place and doing the expected thing helps both you and him. No doubt because of the extra brain power spent on communicating via lights, I was surprised to feel a stronger human connection to the controller compared to talking to that disembodied voice in my headset.

Of course, the veteran KX-155 ultimately returned from the radio hospital via the brown truck, and I returned to the land of the talking. My credit card took a big hit I had been saving for ADS-B (hiss), and some of the fun went out of towered operations. But like an automatic transmission, it’s easier now. Hey, maybe they should ditch the radio and go all light guns at AirVenture. That would be interesting.