Many homebuilders are folks who have been working on cars, trucks, boats and home construction most of their lives. They bring a lot of real-world experience in mechanical work to the task, and for the most part, this is great! Learning good craftsmanship takes time and practice, and most of us that have been working at it for 50-plus years are still working at it, which is the mark of a true craftsman.

While I am a great proponent of bringing skills and knowledge from one activity into another, it is important to realize differences and where those differences lie. The most common expression you hear is that if your car engine quits, you coast over to the side of the road and say a few bad words. If your airplane engine quits, those bad words might be louder and considerably longer—assuming that you have found a good place to set down. So keeping the airplane engine running is considered by most to be a lot more critical.

That criticality in aviation mechanics is important because, for the most part, airplanes fly because they are lighter than cars. Sure, the wings help a lot, but the biggest difference in how the two different kinds of vehicles are built is in weight savings in both systems and structures. Unless you are building a race car, weight is generally a lower priority than strength or reliability, so structure and fittings are less critical. But one other area where aviation places an emphasis is in systems and structural security. In short, we need to make sure that connections (structural, electrical or fluid) stay connected. Because if they don’t, we don’t have much backup to keep us in the air.

Bolt It Down

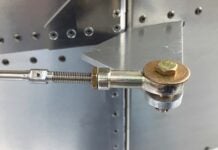

For this reason, aircraft fasteners that are critical almost always have a positive capture design or mechanism. A good example is drilled bolts with a castellated nut and a cotter pin. Safety wire is another—it keeps things from turning once they are fastened in place. Ahhh…. You say, but isn’t the proper torque value supposed to keep things in place? Well, yes, it is, but the safety wire ensures that if the torque method fails, the item won’t loosen and come off. That is the “positive capture” idea. The best thing about positive capture is that you can verify—by visual inspection—that the item has been fully and safely fastened.

Now there are many fasteners on airplanes that do not have a positive capture device—these are mostly in areas that either aren’t critical or are not routinely unfastened. Think nutplates and nylon nuts. In both these cases, friction is added to the equation to keep screws or bolts from loosening up. Most wing-attach bolts are fastened with nylon nuts, and many trim or floor panels are held on with screws in nutplates. The wing bolts are rarely removed and are torqued to specific values, with the nylon “drag” added to keep the fastener from moving if the torque fails. In most cases, those bolts are loaded in shear, so if the nut loosened, the fastener would still take its load anyway.

For screws holding on access panels, floor panels or trim, the added drag from a pinched nutplate keeps the fastener from loosening—a reason why it is poor practice (in most cases) to run a tap through the nutplate to “make it easier to put screws in.” Yeah, it does make it easier—it also makes it easier for them to loosen with vibration. That’s the point—making it hard for the screw to back out—so before you go and modify your nutplates, think about what can go wrong if the fastener loosens up in flight (say with vibration). If it makes no difference, tap away—but in most exterior cases, you really don’t want things falling off your airplane.

Liquid Lock

Circling back to those skills imported from other arenas—let’s talk about the use of thread locking compounds (Loctite is the most common brand name that is bandied about, just so you know what we’re talking about). There is a reason that you will find virtually no mention of it in manuals for certified aircraft or in FAA advisory circulars aimed at mechanics and maintenance personnel. The problem is not that it doesn’t work—it has been proven to work for generations in vehicles and machinery. The problem is that there is no way to verify that it has been used on a fastener once the fastener has been installed. You can’t generally look at a bolt and say, “Yup, that was Loctited,” because the thread locker is hidden from sight in the engaged threads.

It’s easy for a mechanic to visually inspect for cotter pins, safety wire, or lock tabs—but impossible to know if the past person got distracted putting in a bunch of screws and forgot the Loctite—or didn’t read the instructions and realize that it was needed. So Loctite is generally not regarded as a reliable method of making sure that fasteners won’t come out—at least in aviation circles. That doesn’t mean that you can’t use it in non-critical places—but if it is non-critical, why worry about it in the first place? But the inability to verify that a fastener has been positively captured using thread-locking compound is the reason you don’t see it specified in aviation maintenance manuals.

Now let’s not confuse thread locker with torque seal paint. Torque seal doesn’t do anything at all, except to serve as an indicator that a bolt or nut has not moved since someone applied the torque seal. Note that I didn’t say “since the fastener was torqued,” because, honestly, you don’t know if it was torqued properly before the torque seal was applied. Personally, I use torque seal on an aircraft that I am building/maintaining, and I do it to tell myself that I have finished a joint and torqued to final values. But if I open up someone else’s airplane or one I didn’t build, I can’t necessarily trust the torque seal. If it is critical, it needs to be checked.

Because of the critical nature of aircraft fasteners, positive capture needs to be assured and needs to be verifiable (in the field) by those who maintain flying machines. That is why you see so many drilled bolts, castellated nuts and cotter pins—as well as lots and lots of safety wire. Make sure that you can visually check your fasteners—or put a wrench on them to make sure they are tight. And don’t do something on an airplane “just because I do it that way on my car.”

Why is it that spark plugs are not safety wired? And neither are the spark plug wires?

I have wondered this for a long time, but I have never received a good answer.

That is a really good question, and one for which I have no definitive answer except speculation. And I would speculate that spark plugs are never safetied because they were never safetied – historical inertia is a very big thing in aviation! It would also be a pretty annoying job getting down into the fins on some cylinders to do the job.

Paul,

Thanks for the quick response. I guess I have never had (nor ever heard of) a spark plug coming loose, so your answer is no doubt correct.

I thoroughly enjoy your column, keep up the great work!

I was sent to recover a T-6 that literally lost a spark plug in flight. That means neither the plug not the lead was tightened. After replacing the missing plug we checked all the others and found 4 more rear plugs loose. Speculation was that “team” maintenance was to blame with someone hand tightening plugs and leads without proper handoff. Never leave a job incomplete without a positive indicator that it is incomplete.

During the pioneer phase of motorised

UltraLights, I experienced an emergency landing in my KFM. 107 twin cylinder, horizontally opposed, Mitchell Wing B10.

After managing a safe landing in a cow pasture with multiple cows and one very aggressive bull, I had the opportunity to inspect my engine to determine the causative factor. Much to my surprise, I found the left cylinder Champion spark plug center core had come out of the ceramic insulator, and was still attached to the plug wire.

As a former Apollo launch team member, I knew the value of having a back up plan (spares), so proceeded to install a new plug and then managed a very sketchy too short pasture takeoff..gulp!!!

Shortly thereafter I received a critical factory advisory to avoid using Champion spark plugs in the two cycle KFM engine due to the harsh vibrations related to the unique combination. Switched to a different plug manufacturer and never experienced a repeat incident.

My understanding (guess) on the spark plugs is that we have two dissimilar metals, usually an aluminium head and a steel plug. As the engine heats up, the expansion rate of these metals differs with the effect of increasing the torque and tightening the plug.

Love your work Paul, thank you.

That works the other way, makes the plug hole bigger than the plug.