Years ago a friend of mine was faced with commuting for his airline job from his home in St. George, Utah, to his new airline domicile in Phoenix. The existence of a massive ditch—some of you may have visited it on vacation—between those two locales made for quite an extended drive. He decided that an airplane might be the ticket because a direct flight over the ditch was fairly short and the weather was generally cooperative.

He bought a nice older Mooney for the job. To make the numbers even more attractive, he lined up a couple of young time-builders working on their ratings to fly him down to work and then pick him up at the end of his airline trip sequence, usually three or four days later. It was a win/win for both sides—he got cheap commuting on his own schedule and the students hungry for loggable hours got cheap complex time.

On one trip, the time-builder of the week arrived at the St. George airport (KSGU) only to discover the airplane had a dead battery. Most likely because someone left the master on. This particular time-builder was a ramp worker for the local regional airline and would often hook up ground power to the Fairchild Metroliners of the day. He knew that the Mooney also had a plug for ground power and it appeared to be the same type of plug the Metros used. He quickly grabbed one of the start carts from the airline ramp and had to have been relieved to see that the plug fit nicely into the lifeless Mooney. Just a quick flick of switches to power up, hit the starter and he’d make Phoenix on time…

Witnesses say that for a precious few seconds the prop on that little Mooney spun like a turbine. At least until the laws of physics got angry and erupted into a cacophony of arcing, which caused every component of that unfortunate airplane to begin the transformation process from solid to liquid, then through vapor to smoke and/or ash. Apparently the intrepid student didn’t fully comprehend some electro basics like the stew that will get cooked when a system built around 50-ish amps at 14 volts gets force-fed 1000-ish amps at 28 volts. Yowza!

Ground Power for Homebuilts

At first blush it seems counterintuitive to start an article in support of ground-power receptacles with a horror story but I have a reason. Before we get into the nuts and volts, I want to make one thing clear. We often talk of personalization, but there are (or should be) hard and objective standard practices that should be part of every project. One example would be the prodigious labeling of all controls, switches, indicators and so on. There are no valid arguments against such practices. However, there are other things—like this particular topic—that are subjective and merely suggestions that readers can take as they see fit. I will attempt to make my case as emphatically as I can because I truly believe in it for me and my airplane (an RV-10). My next airplane may be different.

After having saved my bacon before with a ground power option on my previous aircraft, I was determined to install the option in my RV and did so in order to have it available prior to the very first power test of a circuit. The main three components are the receptacle, a relay and its switch. The ground-power relay can be exactly the same as the main battery relay and installed right next to it. So as an added bonus if the main battery relay were to ever fail at an inconvenient time or place, the ground power relay can be put to use.

Having the ground-power option allowed using an old but serviceable battery from my boat just sitting on the shop floor. In fact I didn’t purchase and install the proper ship’s battery until the morning of the first engine start—about three years after my first powered circuit test. When the time came, the battery and its warranty were fresh.

During the long period when the instrument panel was being installed, tested, programmed and played with, I would sit for hours at a time on a stadium seat carefully attached to the spar box with the system powered by an old battery that was also attached to a maintainer. I have been assured that using something like a charger/maintainer plugged into a household circuit was fine as long as it went through a battery and never connected directly to the aircraft. That makes the battery a capacitor of sorts for the protection of the aircraft circuitry.

After the Build

OK, the build is never technically complete but hopefully everyone gets my drift. Having an external power receptacle is still quite useful to a flying airplane. It can be used to conveniently recharge a low battery from outside the airplane or jump-start an airplane if the battery is weak. The latter, while useful, should only be considered as a start-and-go-fly procedure if the reason for the battery being weak—such as leaving the master switch on overnight—is understood and no other electrical anomalies are known or present. An airplane that was jump-started should still be carefully analyzed for proper charging during run-up. Nevertheless, the ability to conveniently jump-start an airplane can be a lifesaver, especially in the backcountry or after hours at airports with minimal services.

Some might argue that airplanes equipped with self-generating ignition can be hand-propped. That’s true for a Volksplane, traditional Cub type or most engines below about 340 cubic inches of displacement. Hand-propping an IO-540 can be done, but it takes equal parts strength, skill and experience—and I still wouldn’t bet on it being successful.

What Are the Options?

For hardwired installations, there are basically two choices. The first is the “universal” three-pin type. Some people refer to these as Cessna-type and those outside the U.S. sometimes refer to them as NATO plugs. These are common on Cessna and Beechcraft products and larger turboprops and corporate jets. This is the type of connection that the Mooney and Metroliner in my opening paragraphs shared in common. Any FBO of substance should have cables and/or ground carts equipped for these receptacles. One installation consideration is that they need to be installed internally somewhere and then protected by an access cover or door. Sometimes they are installed in baggage compartments or on firewalls, which can make their field use problematic.

The second option is the single-pin Piper-type plug. This was actually Piper aircraft’s clever factory floor adaptation of an off-the-shelf industrial connection unit that was later adopted by a few other aircraft manufacturers as well, including my previously owned Socata. This connection package is much less expensive to source, much simpler and easier to install, installs externally and is protected by an integrated spring door cover making field use much more convenient and safer.

The Piper-style connections are also commonly supported with cables and carts at most FBOs, with the added bonus that appropriate jumper cables are cheap and easy to make by splicing the male plug to one end of any set of automotive jumper cables. There is also a standalone plug adapter available called a Plug and Jump that can plug into the aircraft’s receptacle. This clever device has exposed pins that allow the connection to any regular set of jumper cables.

Hangar Smarts and Toilet Parts

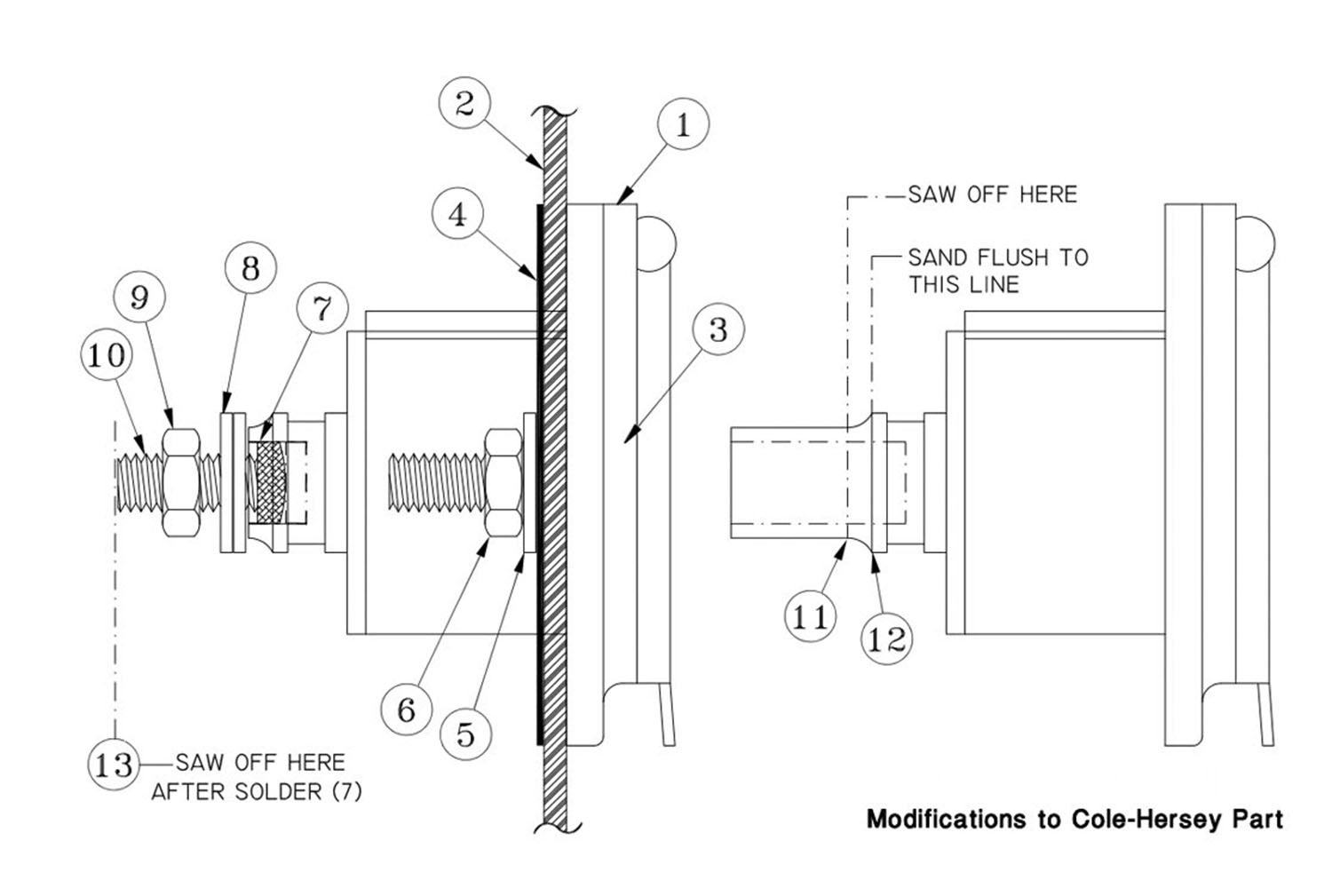

In addition to drastically reducing the chances of getting the wrong amps and volts delivered to your airplane, there is one more very important reason that bolsters my opinion that the Piper-type option is the way to go. Bob Nuckolls, author of The AeroElectric Connection (long considered the bible of small aircraft electrical design), has produced a free pamphlet with detailed instructions and schematics showing how to equip an Experimental airplane with a Piper-style external power receptacle. Everything needed to complete the project is mentioned, including two sets of toilet-seat screws from a hardware store. He also includes part numbers for components from Aircraft Spruce.

I have made use of an external power connection three times in the general aviation part of my career and felt blessed to have had it available each time. That doesn’t count the innumerable hours of electrical testing and glass-panel hangar flying during the build process. I carry a set of plug-equipped cables on every cross-country flight. Having the option available just gives me peace of mind, which the older and more experienced I get, the more I appreciate.

Photos: Myron Nelson, courtesy of AeroElectric Connection and Aircraft Spruce & Specialty, Shutterstock.

Myron,

in electrical connections, the male part has pins.

“The Piper-style connections are also commonly supported with cables and carts at most FBOs, with the added bonus that appropriate jumper cables are cheap and easy to make by splicing the male plug to one end of any set of automotive jumper cables. ”

What you refer to the male plug is actually the female plug which connects to the male jack (the part in the airplane).

So in the picture provided (top left to bottom right):

Piper Male Jack, Piper Female Plug

(green) Male Jack, (red) Female Plug

Joachim, thanks for reading and reaching out. My eighth grade health class teacher might have issues with the concept of inserting a female part into a male receptacle, but I certainly see your point. I guess it comes down to whether one is referring to the plug itself or the internal connections, which in that particular case for me as I was writing, it was the plug itself. Nevertheless, your point is valid and I will revise my thinking and expression on the topic.

Myron,

Thanks for this article. I had already purchased the Piper parts per Bob Nuckolls for my RV-10, and I’ve been concerned about the 14V/28V issue. You say in the article that when using the Piper setup you are “drastically reducing the chances of getting the wrong amps and volts delivered to your airplane”. Does that mean that if you use the Piper setup you’re guaranteed to only get 14V? Are/were there EVER any 28V airplanes that used this system?

Hi Ted. Thanks for reaching out. The only guarantee is your vigilance. Yes there have been 24VDC aircraft use the Piper plug system. My previously owned Socata was one of them, but I would consider them rare. Nevertheless, inherent to the Nuckolls design is the integrated “crowbar” over voltage apparatus to protect the system.

While there is obviously overlap, as a general rule the three pin system is geared more towards larger corporate aircraft and small airliners while the Piper single pin towards smaller, mostly 12V personal aircraft.

FBO Start carts vary anywhere from fancy electronic rigs with fully adjustable settings to simple batteries strapped to hand trucks. Good luck.

Thanks for your response. I did try to get Nuckolls’ crowbar setup working using an RCA SK9346 Crowbar IC but I can’t find an example schematic or even a data sheet for that device, and when I hooked it up in the obvious way, it smoked. The B&C Crowbar Module Bob suggested is no longer available. So I guess it’s down to vigilance, as you suggested. At least there’s less chance of 28V hitting the airplane with the Piper plug, even though there’s no guarantee. Does anyone else know of a crowbar device that’s actually available (and documented)?

Try Digikey or Mouser

The Nuckolls setup should work fine, because when the overvoltage circuit trips, it bypasses the ground power contactor coil, at least until the fuse blows. But the RCA SK9346 is only rated for 2 amps, and the Nuckolls crowbar setup has a 5A fuse. However, the Stancor 70-902 contactor Bob suggests has a coil resistance of 16 Ohms, which means it should conduct less than 1A of current at 14V. Not sure why Bob chose to use a 5A fuse in this application. If you change the fuse to 2A, The SK9346 might have enough umph to blow the fuse without smoking itself. And if you’re handy with a soldering iron, you might be able to make your own crowbar circuit using an MC3343 (https://www.onsemi.com/pdf/datasheet/mc3423-d.pdf) , a few resistors, and an SCR such as a 2N6504G.