You hear it all the time from pilots gathered around the hangar. “I should get my seaplane rating.” “Yeah, I’m kind of working on my tailwheel endorsement.” “I’m thinking about building an airplane.” And then there’s, “I should get my A&P.”

You hear it all the time from pilots gathered around the hangar. “I should get my seaplane rating.” “Yeah, I’m kind of working on my tailwheel endorsement.” “I’m thinking about building an airplane.” And then there’s, “I should get my A&P.”

As someone who just graduated from a Part 147 school and as the proud new owner of an A&P certificate, I’m hoping I can shed some light on the experience and help you decide whether getting an A&P is worth it. I also have some perspective on how prepared or unprepared you may be as a brand-new mechanic and how it can help you in building and maintaining your own kit airplane.

Similar to having my flight instructor certificate, I quickly learned that an A&P certificate earns respect in the aviation community. Also like the flight instructor certificate, I don’t feel like I’ve necessarily earned that respect without getting my hands dirty and gaining some experience in the discipline—between working on my GlaStar and plans to volunteer at local warbird organizations, I will get there eventually.

Perception vs. Reality

A common perception of A&Ps is that they are savvy miracle wizards with auras of knowledge that can do any kind of work on any kind of airplane with the utmost confidence. For the seasoned A&P that may be true but simply getting the license will not guarantee any such magic.

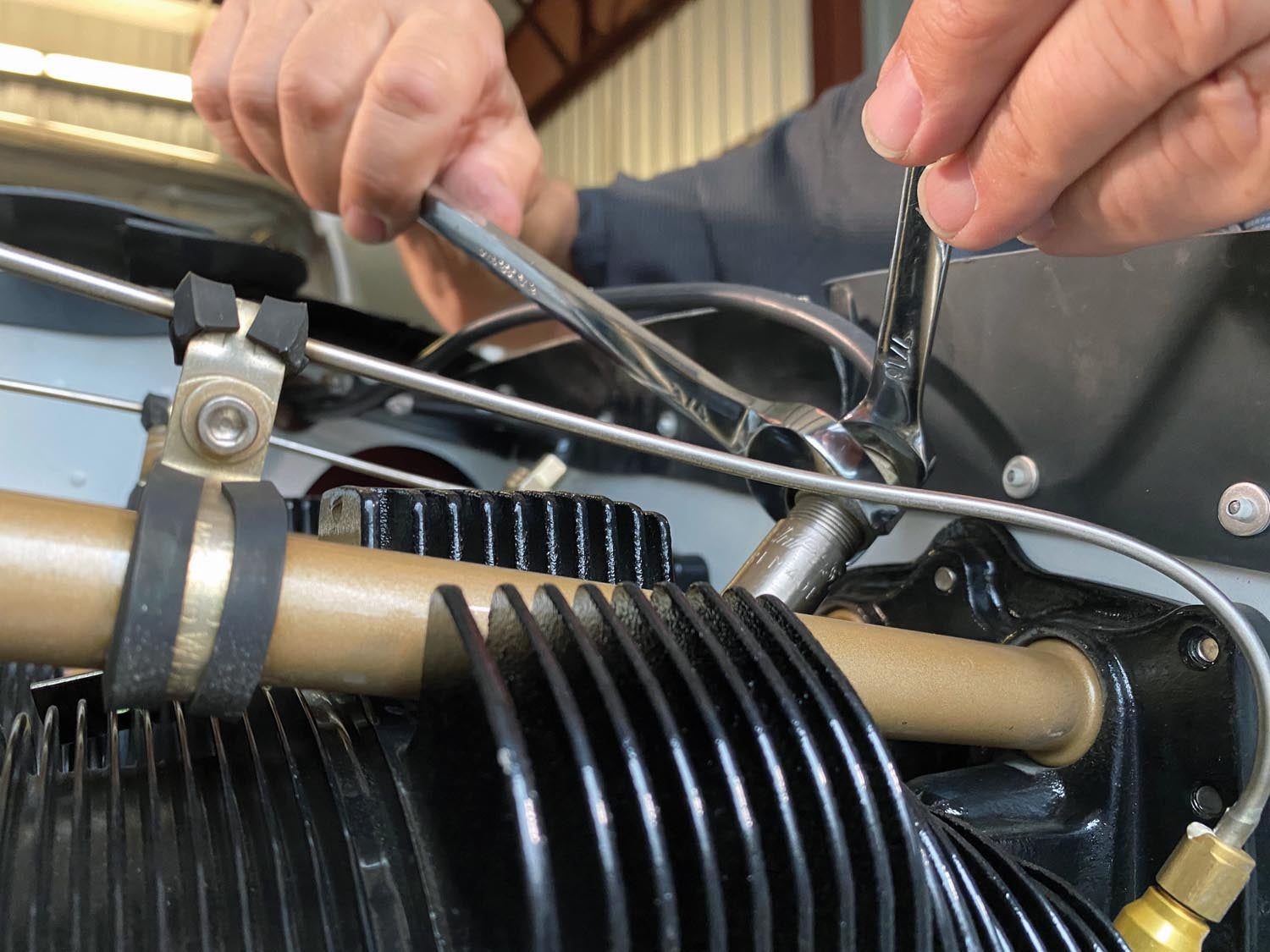

In 2021, freshly (honorably) separated from the U.S. Coast Guard, I moved to Denver and decided to take a “break” to attend A&P school while searching for the next full-time flying gig. The COVID scare had left local flight instructor jobs impossible to come by that summer, so I began working part-time in an aircraft maintenance shop while attending school. I learned a lot. But what I found to be most helpful was my existing background, which was 10 years of flying and nine years of airplane ownership with consistent hands-on owner-assisted maintenance. Many tasks in A&P school were consequently a non-event, especially after getting refreshers at the shop job. Servicing an oleo strut? Compression check? Changing a tire? Timing magnetos? The instructors practically had me teaching the class for such things and, looking back, I had an entirely unfair advantage over some of my colleagues, a few of whom were holding a wrench for maybe the third time in their lives. For much of my time at the school I wondered, “What am I really doing here? Have I really learned anything?”

Then I had an epiphany. In the last three months of my total 14 spent, I realized exactly what the school had taught me. After digging through hundreds of maintenance or overhaul manuals and completing oodles of projects, I realized that I was not being taught to do maintenance on airplanes based on the experience, repetition and memory I had so far relied on. I was being taught to use basic mechanic skills and then know how to find and use the appropriate resources and follow directions!

It’s a mindset more than anything. Instead of thinking, “I can’t do this because I’ve never done it before,” I was changed to think, “I can do this, I just have to slow down, do my research and pay attention to the manual(s).” The final A&P testing is done in two parts—an oral and a practical. The oral is knowledge-heavy, requiring you to show a foundation of understanding in aviation systems. No notes or resources are allowed. That information must live in your brain.

The practical can be boiled down to your attention to detail, ability to follow instructions and ability to complete the required paperwork. You are also tested on required legal knowledge, as A&Ps are the front line of defense when it comes to what’s legal and safe versus not legal or not safe. The nearly two-year process really hammers home the concept of responsibility. In the end, you are mostly being taught to use your resources: approved manuals, diagrams, FARs, AC 43-13-1B and type certificate data sheets. Here I can see the advantage of going to a Part 147 school versus getting an A&P through apprenticeship, though a good test prep school should bring you up to speed on all things legal if you are considering the apprentice route. What an apprenticeship may lack in technical knowledge, it would likely make up for in really useful hands-on experience.

On the Job

My first action as an A&P was to install Rosen sun visors and fill out and send off the Form 337. That went smoothly as it was about the simplest job imaginable with very clear instructions. Next, I was asked if I could change some light bulbs in an aircraft I’d never worked on before. Sure, that’s simple. Uh, well. Yikes. Changing the lights turned out to be a lot more involved on that one than the typical airplane. I responsibly declined to touch it without any manuals or instructions. (See, I did learn.) Lucky for those of us in the Experimental world, we don’t have to worry whether we use Textron-approved sealant or the other intricacies of type-certificated aircraft.

That said, is getting an A&P of any use to the homebuilt owner? The first answer is obviously yes if you are in a position such as mine and purchased your airplane already built. As an A&P, I can now sign off my own annual condition inspections. (Woo!) What about if you are considering building an airplane? I had one classmate who attended A&P school just for that reason. As a first-time aircraft builder, he attended to sharpen his skills before building his dream Van’s RV-8. Mostly he wanted to take the riveting class, but he slogged through other classes to get there. He told me that his experience was not entirely helpful nor worth it to him, especially due to this particular school’s administrative shortcomings. I wholeheartedly agree with his observations and refrain from speaking on behalf of all A&P schools, but I think there was a severe lack of hands-on experience gained in our school—luckily that was something I already had and was able to show up with.

So, would it be worth it to you? Only you can answer that question. Chances are, you already possess most of the skills and knowledge a Part 147 school could realistically teach you—but I promise you’d still geek out occasionally because it is airplane stuff. It’s still possible that you’ll learn a lot, especially if you don’t have a strong mechanical grounding. But be prepared for substantial cost. Consider it an investment in yourself.

Was it worth it to me? Yes, for the end result of having my license. Was it easy? Yes and no. Around five months in, I finally nailed down a CFI job and consequently switched to night classes. Just like me, everyone around me had a full-time day job and we were all running on a perpetual 3 to 5 hours of sleep each night. A common theme among the late-night project talks was, “I wish the time commitment had been more clearly explained.” And here is where I throw in a zinger. Right as I stepped away with my certificate in September 2022, the FAA revised Part 147 to be a skill-based curriculum instead of a time-based curriculum. So, prior to that change, instructors and students alike were desperately trying to find ways to kill time when we couldn’t legally clock out and go home but had no work left to do. If you were a Type-A personality, a busy person or a mechanically competent person, it would drive you mad! I am excited for the change but upset it couldn’t have happened sooner.

There are some things I learned from A&P school that I didn’t know as much about before, such as electricity, troubleshooting, hardware nomenclature, the painting process, riveting and sheet metal, forming aluminum tubing, formulas, available resources, best practices and more. However, I feel the system is generally designed to bring people with little experience or background in aviation up to a standard, with an emphasis on learning to follow manuals. If you are already a savvy aviator and preventive maintainer, it may not be a revolutionary experience for you, though the opportunity to dig into the books and learn strategies for learning what you don’t know may pay off down the road.

Do I feel more prepared than before? Not terribly, but I am armed with slightly greater knowledge of best practices and my new mindset to hunt down information when needed and follow it. As with any FAA certificate, it is a license to learn.

Gee Amy, thanks for the article. Maybe I either went to a better A&P school or got more out of it. I had retired from my day job and found the school fun (most of the time). Did I find it useful, definitely. It made a different on the construction of my experimental Rans S21, now flying, as well as the speed and accuracy of construction. Also, I find it useful in teaching a bunch of high school students building an RV12 who started off not knowing what end of a screwdriver to use or how to read a manual. Certainly carry on, there are lots of things you can do with an A&P other than wrench on aircraft.

Well done Amy! Good things to consider as a 70year old pilot, chronic gear-head, FAA LSRM-A holder and owner of an EAB Cub. That I can’t do the annual inspection on! I stopped by the engine shop at my airport to get an air filter for an owner assisted condition inspection on a C-150. The shop was looking for HELP! Possibly an A&P in my future and you made it clear that apprenticeship is possible.

Mark Heule

EAA 237

This answered the question of, “will it make me a better builder” as I would have guessed. I’ve built and RV10 and have been flying it for 10 years and 1400 hours. Before that it I had only wrenched RC models. I had owned a Maule but barely touched it because I felt unworthy. No A&P training here.

For building I got a TREMENDOUS boost by attending a week long RV tail building course where we attempted to build all the tail feathers. The hands-on metal work was all I needed to complete the metal portion of the kit. I had some composite experience but attended a weekend composite class boosted my skills significantly. I later attended Lycoming’s engine course. With those 3 targeted training experiences I was able to complete all aspects of the build without further hands-on assistance. All the training directly applied to the RV build which is critical. No one other than this builder -flyer-maintainer has needed to touch my aircraft… yet. I won’t be overhauling any engines or even pulling a jug but I feel I can maintain this once new engine through most of it’s working life before sending it off for a refresh.

I had the opportunity to do the last 2 months of my build in a hangar beside an experienced AP. I lent him my extra hands and gave me the opportunity to see some real line maintenance work. Interestingly, he didn’t feel qualified to help me much since he had little experience with RVs or experimentals but working beside him was invaluable.

Going to AP school seems like overkill for this builder-flyer-maintainer. Targeting one’s training to the specifics of their build would be most cost effective methinks.

I went to a community College A&P school not a for profit school. I felt I got alot of hands on. I was planning to be a mechanic but the industry took a downturn in 93 when I graduated. Still glad I did it. The mechanical knowledge is great. Everything from hydraulics to just using a multi meter is covered. As mentioned by others probably overkill for building your own plane especially considering the knowledge you can gain from youtube for free. It was also alot cheaper back then. I think it was about 3k for the whole program.

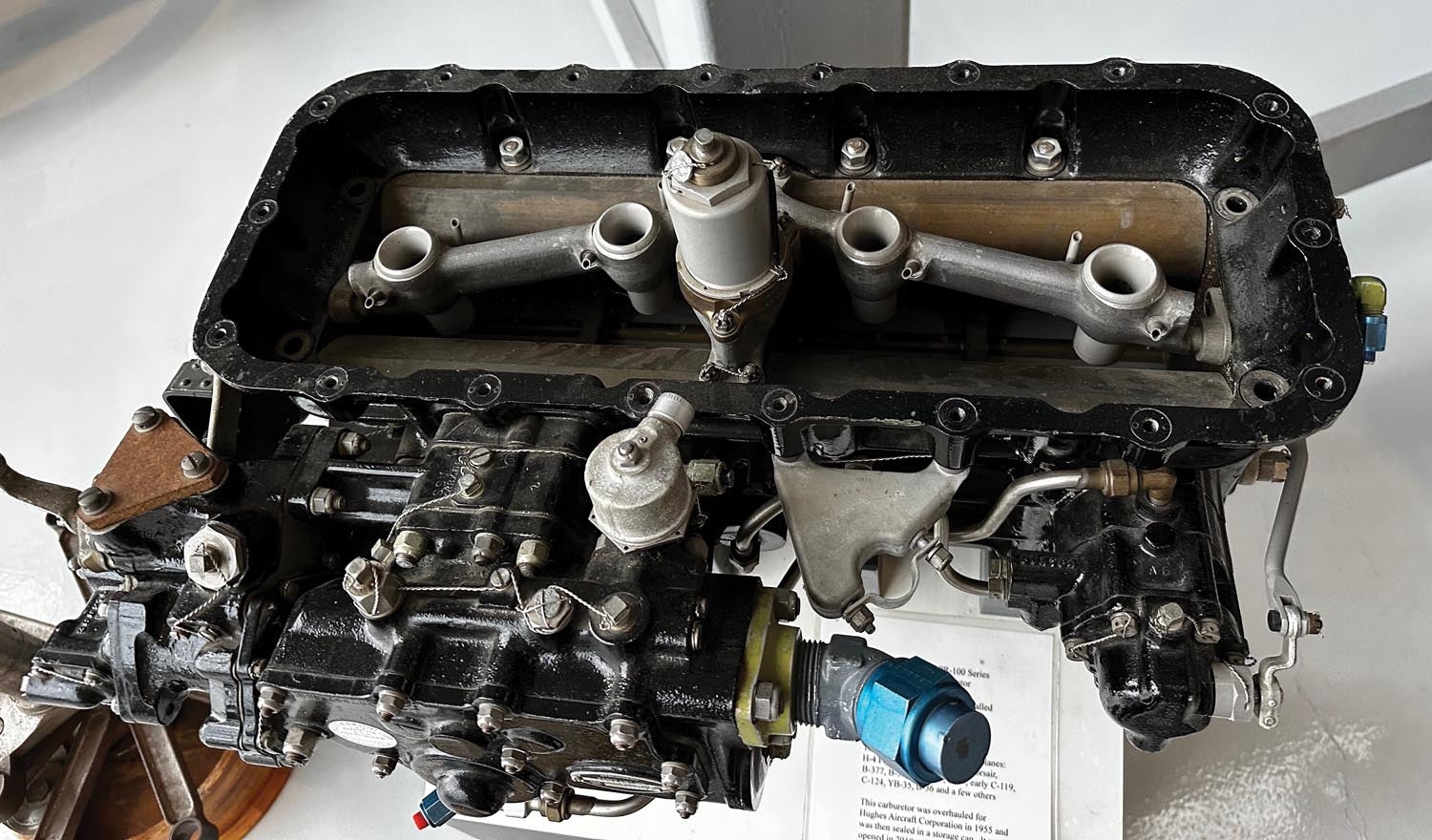

Thank you very much for your article which seemed like perfect timing as I’m considering taking A&P coursework. I’m interested in becoming a first-time kit builder, and I am wondering how useful the classes would be. I am curious, though, about one potential benefit of having a Powerplant rating that you did not mention. One of the biggest expenses of a kit plane, or any plane for that matter, is the engine. With your rating, would it be possible for you to overhaul a ‘cored’ engine to save money on that engine over buying an engine overhauled or remanufactured by someone else? This would seem to be a significant financial advantage now that you’ve already made the investment in your degree. Many thanks!

Hi Neal,

In A&P school we did tear apart and rebuild a piston engine. I feel fairly confident I could do it on my own, but I would personally still want someone experienced looking over my shoulder!