In my earlier article, “Chasing a Better Backcountry Experience” in the April 2023 issue, I promised a follow-up on the importance of matching a tailwheel to the terrain. Today, pilots have more options other than what used to be limited to a Pietenpol-type steel harrow skid or a J-3 Cub-type leaf spring assembly. The skids could not be used on pavement and the leaf springs provided a rather stiff ride. There was little to tinker with other than the number of leaves and the vertical orientation of the tailwheel shaft. Most advances were in the wheel assembly itself, with Scott tailwheels becoming one of the better-known examples.

Fast forward to today’s backcountry experience, with many pilots seeking the thrill of landing on short, unimproved strips in the beautiful and scenic canyons and mesas of Utah, Nevada and others.

On my trips to Utah I’ve witnessed deep ruts, prairie dog holes, soft sand, small boulders, dirt-encrusted clumps of grass and short scrubs with thick stems. So far, I’ve been fortunate and have learned to be somewhat choosy about where I’m willing to land my Murphy Super Rebel. To stay out of trouble, I prefer a minimum of 1500 feet of usable hardpack gravel or dirt-type strips, such as Cedar Mountain, Wee Hope, Mexican Mountain, Mineral Canyon and Hidden Splendor. But even then, you can often find ruts, especially on slopes.

My airplane has a long, hardened-steel stinger with a tailwheel bolted to the end. Consequently, if I encounter a rough surface on rollout, distance permitting I’ve learned to lift the tail until the groundspeed dissipates. This provides for a smoother ride and less stress on the airplane’s tail. Historically, that’s what backcountry pilots had to learn, and I learned the technique from my friend Mike Marker. It’s what he perfected in his Murphy Rebel and Carbon Cub EX before experimenting with a new tail suspension system.

For a moment, remember the PA-18 Super Cub, the Citabria and Husky were all built on six-inch axles with up to 8.50 tires. Over the last decade, as the main landing gear tires grew up to balloon size, the little tire in the back also had to change. Larger tires allowed pilots to land on rocky riverbeds and numerous other rough surfaces—obstructions that could rip a tailwheel off the aircraft. As the little wheel grew larger, there was still increased stress on the tail structure and the ride didn’t improve much. As a result, several Experimental aircraft companies realized the bolt-on leaf spring found on most steel-tube-and-fabric aircraft provided an opportunity to simply attach a new tail suspension system.

Mike installed the first generation of the Airframes Alaska T3 suspension on his Cub in 2016. The suspension was a simple bolt-on replacing the Cub’s leaf spring. The weight of the T3 suspension was less than 0.3 pounds more than the leaf spring and was very effective at reducing the stress on the aircraft and occupants during their frequent trips to the backcountry. In fact, Mike’s wife, Jan—who has battled chronic back pain for years—experienced a notable improvement in comfort with the new suspension.

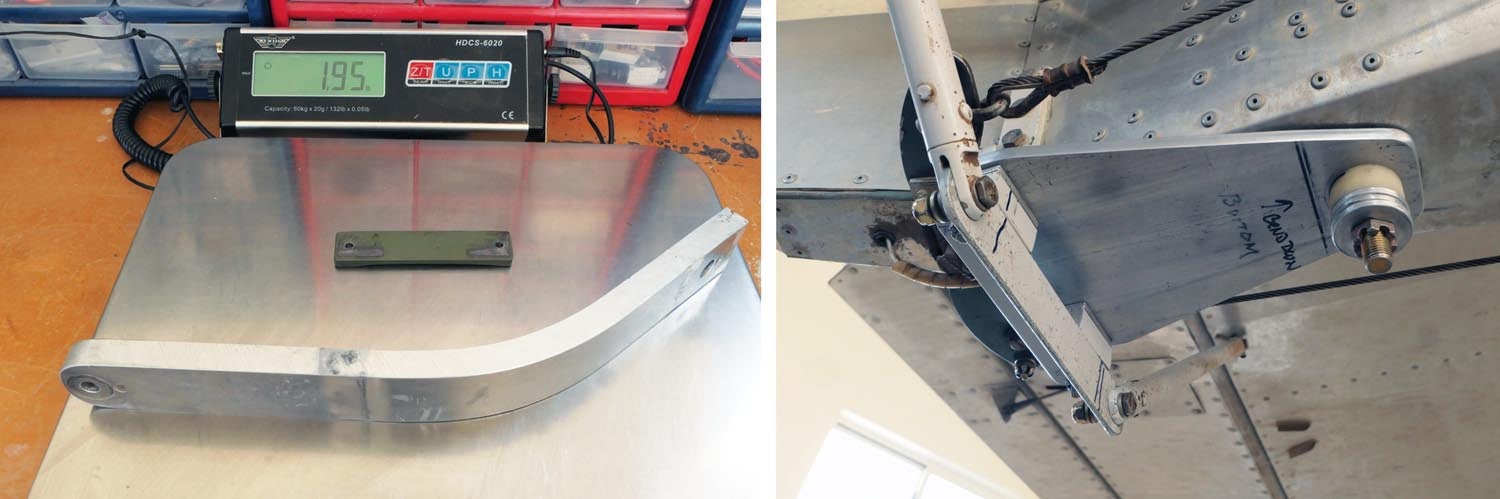

After the aluminum tailwheel spring on his Rebel broke in half, Mike also installed the latest improved version of the T3 tailwheel suspension on his Rebel in July 2021. This installation was not a simple bolt-on because the T3’s bolt pattern didn’t match the Rebel’s mounting brackets. Instead, Mike fabricated a 1/4-inch-thick aluminum adaptor plate, which transferred the suspension load to the airframe. The T3 suspension plus the adaptor plate was 3 pounds heavier than the Rebel’s aluminum spring. Mike and Jan have made over 270 landings on the new tailwheel suspension without any problems.

The wonderful aspect of Experimental aviation is that companies can provide rapid improvements based on field experience. Mike experienced two failures of the early version of the T3 suspension on his Carbon Cub EX. The first failure was the shock spring shaft. Airframes Alaska immediately sent him a stronger spring assembly. The second failure occurred in July 2019 at the swing-arm strap. Again, Airframes Alaska forwarded him an upgrade kit with a one-piece swing arm. It has now performed wonderfully on more than 1000 landings in the backcountry.

My friend Ted Waltman, who flies out of Western Colorado into the Utah backcountry, built a Backcountry Super Cubs SQ-2 (STOL Quest, a Wayne Mackey design). He installed the Acme main landing gear and tailwheel suspension system on his aircraft and now has hundreds of landings with no problems. Both the T3 and the Acme tail suspension system take similar approaches, although the T3 incorporates a compression spring around a shock absorber and the Acme system incorporates a nitrogen-filled cylinder. Both have multiple adjustments and various features unique to each system, all highlighted on their respective websites.

As you can see from the photos, Mike and Ted frequent shorter and rougher landing strips than I’m willing to attempt with my Murphy Super Rebel. To date, there are no simple ways to improve the tailwheel suspension on my airplane (although I’m told Murphy Aircraft is in talks with one of the major landing gear suspension companies to solve this problem). Again, one of the wonders of Experimental aircraft.

Photos: Mike Marker, Ted Waltman and Jerry Folkerts.

Hi Jer,

See what you will be missing…

Excellent write-up as expexted