I may be guilty of sitting on this story too long. In 2003, on the eve of my employment in the kit-aircraft industry, an industry insider came to me with his story, a warning of sorts. This person—I’ll call him “Bud”—asked me to meet him in the parking lot of an abandoned Oshkosh restaurant. He told me he’d be waiting in the shadow of the eaves, briefcase at his feet, smoking an unfiltered cigarette and wearing an old EAA windbreaker. The seriousness in his voice compelled me to see if the bag of goods he was selling was fresh fruit or yesterday’s bagels.

If the meeting had turned out as I expected, you would not be reading this, but this man held information only someone deep inside the industry could know. When I asked why he reached out to me, he threw his cigarette to the damp asphalt, ground it flat with two twists of his foot and began to walk away. I grabbed his arm but he shrugged me off. In doing so, he paused long enough to reconsider. Without speaking, we had come to an agreement. He would talk. I would listen. When quoted in this article, his voice has been altered to protect his identity.

Deception and Propaganda

Bud’s soliloquy covered the gamut of the kit industry, but on one point he was clear; his comments were about the successful kit manufacturers, not the ones with non-flying mock-ups, mahogany models of what could be and an unbeatable introductory price. This was about the designers who have kept the deception going so long that hundreds or thousands of their aircraft are flying.

Bud said the deception starts with the print ads, sales literature and

internet propaganda. That was his word, propaganda. He showed me photos of kit parts neatly spread across a hangar floor or bathed in the light of a setting sun. “Look closely, kid.” He called me kid, though I was 42. “This photo is filled with lies.” He shook the image so hard I couldn’t focus on it. I think his days were fueled by caffeine and nicotine, his nights calmed with Cabernet. He reached into his briefcase and pulled out another photo. “Look, Champ,” he said, pointing to an inkjet image he printed from a website, “This shows four large bags of rivets, and I know for a fact there are three large bags and two small ones.” His excited finger danced across the image, “And here! This part isn’t black anymore, it’s red. It confuses the builders.” A chill chased down my spine. I had underdressed for the damp night.

Pulling out a price sheet, Bud continued, “Look here, Chief.” (Having forgotten my name, Bud began calling me names of Aeronca aircraft.) “Says it includes complete hardware kit. It ain’t no more complete than a steak and egg breakfast without Tabasco and a toothpick.” Before continuing, he put his briefcase aside to light another cigarette. It was obvious he was about to speak from his heart. For this he needed no web printouts, no glossy brochures. He took a long drag from his cigarette and, exhaling, mixed the word hardware with carcinogenic smoke. Falling silent, he took another drag from the cigarette, its end pulsing like an anti-collision light. Then, oddly, he said no more. His eyes drifted off with his thoughts. I also remained silent, as I had agreed.

Redefining “Complete”

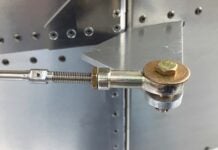

In my conversations with builders, I often recall my meeting with Bud. I understand his long pause before uttering that single word—hardware—and his silence afterward. I’ve audited plans for the hardware needs of four different airframes. It sounds simple, but it goes off the rails when options come into play. Center stick or dual stick? Tailwheel or tricycle gear? Hydraulic or mechanical brakes? Different propellers and engine options need different hardware. Drawing revisions can alter the hardware needs of an airframe. It’s difficult to update the contents of a hardware kit in step with a drawing revision. Plan changes may impact builders who already have hardware kits. Let’s not discount the human element in compiling a list. I know if 100 people were given the same plans, 100 different lists would be created. If all of that weren’t enough, a hardware kit can’t account for builder modifications or a bolt that skittles, unnoticed, under a workbench.

In a perfect world the word complete would be stricken from any description of an airplane kit. As that will never happen, let me reframe what complete should be taken to mean, particularly as it applies to hardware. A hardware kit is complete if you received everything you paid for and what you paid for is itemized on an invoice or packing list. If an item is listed that you didn’t receive, there was a packing error and you are owed that item. If you need hardware you weren’t supplied and didn’t pay for—and you will—source it from anywhere you wish, whether that be the kit manufacture (if they sell it), a hardware vendor, a hangar buddy, a hardware store or a nearby A&P or FBO. Helpfully, some homebuilder suppliers sell generic hardware kits that contain a wide variety of AN hardware. These kits supplement a manufacturer-provided hardware kit, fly top cover for hardware that is lost or gets damaged and accommodate modifications. Purchasing a generic kit at the beginning of a project will pay dividends in reduced delays, shipping costs and frustration. Still, anticipate having to order hardware on occasion.

Bud’s frustration was compounded by being an old-timer whose career began when homebuilts were built from plans, not kits, and homebuilders understood they’d need to source the materials and hardware themselves. Today, kit manufacturers work hard to provide as much as they can, but it’s a challenge without end, and the more complex an airframe is, the more likely absences will exist.

I realize the above article is written somewhat “tongue in cheek.” However, there are vast differences in kits from different companies. The kit I bought did nothing about firewall forward except providing five engine mount drawings for five alternative engines. The drawings were of such a quality that the engine mounts could not be manufactured without having the specific engine and firewall on hand. There was no electrical drawing or electrical equipment at all. The canopy design was such that it had a propensity to come open in flight. The aircraft was designed to maximize the Light Sport Rule, but had no aileron balance. Eventually there was a massive rebuild of the wing spars, fuselage spar carry through, aileron balance added, and many other parts added or altered, which took about 600 hours to accomplish. Maybe you know the aircraft being described.

Hi Stuart,

Thank you for commenting. it sounds like you had a bad experience.

While the meeting with “Bud” was certainly tongue-in-cheek, the takeaway of the column is not. There is no accepted definition of “complete” in the kit plane industry. It can range from the now-legendary Christen Eagle kit that purported to truly include everything, to a Pietenpol tail kit that is nothing more than strips of Sitka Spruce cut into raw lengths. It is common for kit manufacturers to leave out avionics, wiring, plumbing, etc., as these items–particularly avionics– can be very personal choices and can hinge on what engine is installed, another very personal decison.

A builder who is not interested in such decisions can still enjoy building by choosing something like an E-LSA Van’s RV-12, which MUST be built exactly as the factory model. That takes decisions out of a builder’s hands, but it also limits personalization.

Everyone who considers a kit must determine for themselves if a kit designer’s definition of “complete” conforms with their own and should be prepared to source additional materials to complete their project.