It is said that one thing leads to another. That being so, I credit my career to the word drafting on my seventh-grade class schedule. I had no idea what drafting was but my schedule summoned me to appear. I embraced it. My teacher, Mr. Gerber, fed me ever more challenging assignments as I tore through the self-paced lessons. When the school year gave way to summer, I set about to draft everything I could find. While my friends rode their bikes, I plied my dad’s T-square and templates on velum.

It was a non-traditional summer for a 13-year-old, though I still made time to catch crayfish with sausage casings. In high school, my drafting prowess secured me a job with an industrial machine-tool manufacturer. My supervisor, in charge of the installation, operation and parts manuals, expanded my skills to include technical illustration and writing. Twenty-five years later, those skills filled a need at a fledgling aircraft company named Sonex Ltd. I had a Sonex going together in my garage so the jump from builder to employee made sense—and may have been instigated by me with a multi-year pressure campaign. Yes indeed, one thing can certainly lead to another. Yet, remarkably, nothing ever leads me to my vacuum.

Skills Are Skills

I was gathering airplane-building skills and knowledge before I knew I’d need them. In addition to drafting, Mr. Gerber introduced me to metalworking, pop riveting, woodworking and the properties of Plexiglas. Of course, they aren’t aircraft building skills. They are simply skills. I was 13 when I cut my first rabbet, for a bookshelf. Ten years later, I’d cut rabbets for the tail of a Pietenpol. A rabbet is a rabbet. There are no aircraft rabbets. Seventh-grade shop laid a solid foundation for my homebuilding adventures. These days, when Sonex canopies are being formed, the smell of hot Plexiglas takes me back to Mr.

Gerber’s classroom, his hoarse voice, his peculiar way of pronouncing glue (gah-lou) and his liberal use of cologne.

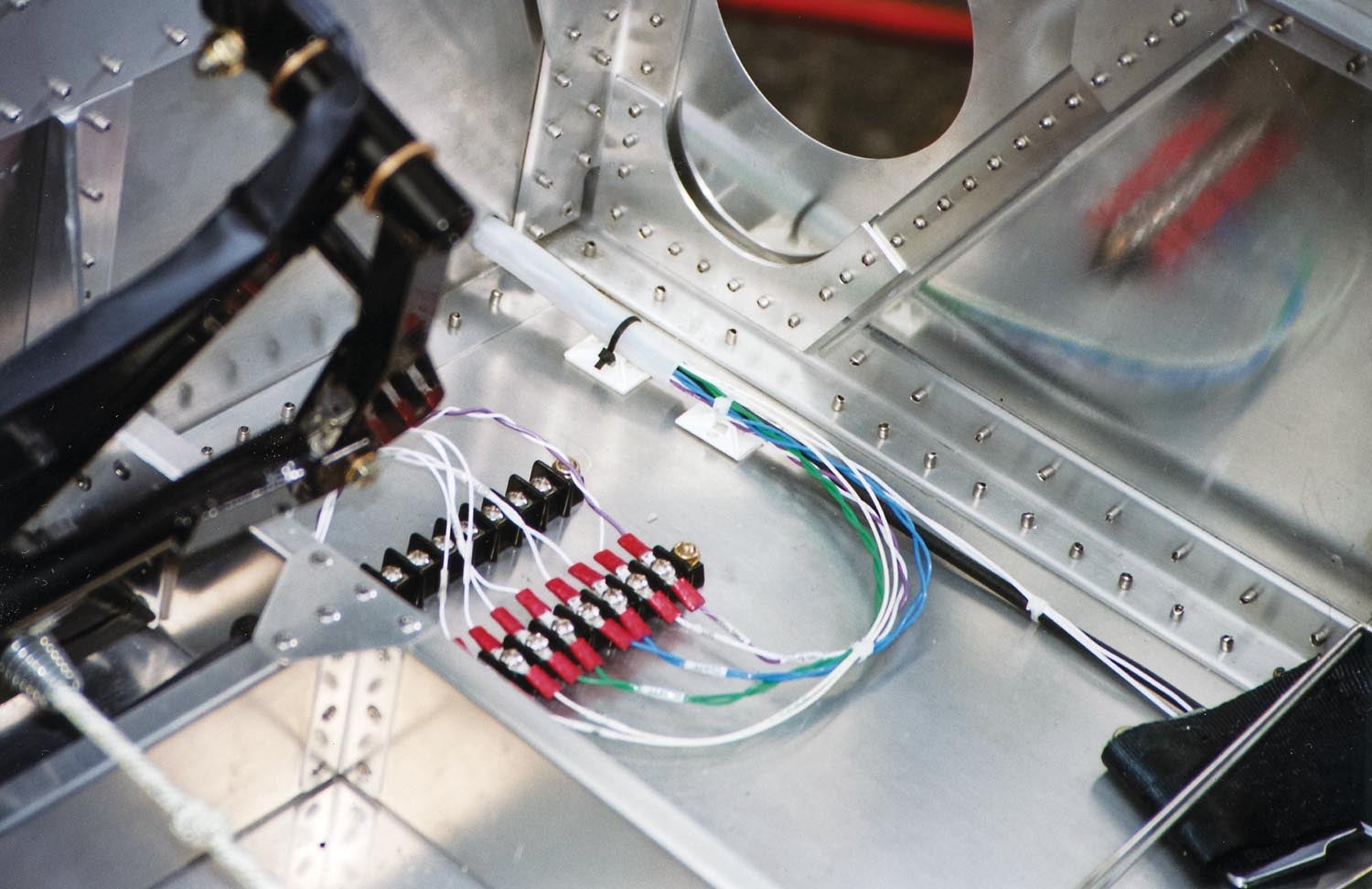

If you are new to homebuilding, rest assured you are not starting from zero. (Well, one person may have, but we’ll get to that.) Long before you picked up your first issue of KITPLANES®—lured, perhaps, by the possibility of owning a P-51 (if only in shape)—you were gathering knowledge and skills necessary to carry a project forward. Aircraft building knowledge isn’t sequestered in an aviation tome any more than Malco snips and microballoons are exclusive to aviation supply companies. There is no such thing as an aircraft riveter; there are only riveters. There is no aviation-grade aluminum; there is only a variety of aluminum alloys, each suited to a certain task. There is no such thing as aircraft wiring; there is only wiring.

Before engineers jump in with lengthy rebuttals, let me add that there are best practices in aircraft building. For example, while you can wire an Experimental with automotive wire, best practices dictate the use of Tefzel wire. The principles of a circuit remain unchanged, however, whether that circuit exists in a homebuilt, a Harrier or a hot rod. It also holds true that bleeding the brakes of a Kitfox is no different from bleeding the brakes of a Zenith, which is no different from bleeding the brakes of a motorcycle or car. This becomes obvious when you focus on the goal—removing air from the system—instead of the vehicle in which the system is installed.

For many years Sonex held builder workshops. An important part of the workshops had each participant building a wing leading edge project. The project introduced nearly every skill needed to build an aluminum airframe. As years went by, a growing number of attendees didn’t participate in the hands-on portion, citing their intent to purchase a quickbuild airframe or a used, flying aircraft as their reason. “I don’t need to form a rib because I’m buying a kit.” They missed the point, which wasn’t to make a rib, it was to learn a skill that could be applied throughout their project.

I found the lack of interest in acquiring skills curious and disappointing. I knew their homebuilt aircraft ownership experience was going to be a negative experience. They were fooling themselves to think they’d never need the skills or could always find a qualified and willing mechanic to make necessary repairs. I wondered, then and now, why someone would become involved in a hands-on hobby without wanting to be hands-on. Which brings me to this…

My sent-email folder suggests builders have asked me questions related to the construction, operation or maintenance of a Sonex product more than 70,000 times. That number easily exceeds 100,000 with phone calls. Those questions include how to crimp wire ends, adjust valves, bend aluminum, bleed brakes, torque bolts, drill holes, press steel bushings into rod-end bearings, set pulled and solid rivets, cut inspection holes, cut Plexiglas, cut Lexan, cut lead, cut fiberglass, read blueprints, read micrometers, read angle finders—I could go on. If you review that list you’Il see most of the topics are not design-specific and few are aircraft-building-specific. My all-time favorite/least-favorite question was a person who asked how to tighten a nut, explaining they had never tightened a nut in their life.

This leaves me wondering, where is the line that separates a Sonex from a skill? By that I mean, is it an aircraft company’s responsibility to teach the skills needed to build their product? Is an aircraft company that sells a tube-and-fabric kit responsible for teaching their builders how to weld? I’d say no. Ford doesn’t teach you when to use a turn signal (casual observation would indicate no one teaches that anymore). However, their manuals describe where the switch is located and how it works in their vehicles. Canon instructions explain how to download photos from their cameras but not how to organize the photos on your computer. A paintbrush manufacturer doesn’t tell you how to prepare water-damaged wood for staining. My point? Anyone who chooses to build an airplane should be prepared to acquire the needed skills and knowledge from a multitude of sources. But there’s good news…

Think, but Don’t Overthink

The skills needed to build an airplane are not unique to aviation, nor are they uncommon. Builders stumble, though, when they contemplate applying a common skill to building an airplane. The skill takes on mythical proportions. That stumble can prevent a project from starting or stall its progress. (In the category of “can’t make this stuff up,” as I wrote that last paragraph, I spoke to a builder who told me his project was delayed a month while he fretted over cutting an inspection hole in a wing skin.) I’ve heard it said by an EAA Homebuilders Hall of Fame inductee, “It’s not like you’re building an airplane.” The gist of that statement—only slightly tongue in cheek—is don’t overthink the task at hand.

I’ve assured worried builders that the pieces and tools have no idea they are part of an airplane project. My oldest grandson was 6 when he gazed upon an AeroVee engine and a photo of its individual parts and said it looked more complex assembled. (Yes, he said “complex.”) He saw parts to be assembled, one at a time, like a Lego kit, where others saw an intimidating airplane engine. We’d all do well to approach our projects with the unfettered mind of a 6-year-old and the skills once passed to unwitting seventh-graders.

Great article!! I also have fond memories of shop classes during high school! My dad was more than willing to work on a variety of projects when I was a kid, but he passed away when I was 14. Luckily, the welding, automotive and shop classes helped build upon those skills. My twin brother and I also had plenty of projects to work on at home.

More recently, I’ve “finished” build my shop/garage and have started on a tail kit of a well known airplane.

While the sample kits from EAA and the other airplane kit manufacturers are great for adults, I can see the need for a kit more specifically geared for Tweens or Teens. Something reasonably small that is quick and easy to assemble during a fly-in event. Just enough to give them a taste for building skills.

While it would have been nice to have those great EAA videos when I was fabricating the infamous Legacy Sonex “tuning fork” back in 2003, I wouldn’t have met all the cool people who patiently pointed me in the right direction, though. That, along with a keenly-developed love for researching new building skills or techniques, has been the essence of homebuilding to me.

As a Mechanical Engineer and aircraft builder (Sonex in fact), I whole heartedly agree! I keep trying to stress this fact all the time. But the FAA treats everything aviation as magically different and keeps it all behind massive regulation and unnecessary cost. This falsely leads people to believe that aviation is different somehow, that the skills are different. The skills I’ve learned throughout my life (and as an engineer who started out as a drafter), have made building easy. I’m still learning new things constantly, of course, but it’s all do able and accessible. There is nothing magical about aviation aside from the FAA regulations and its uniqueness due to only a small portion of society partaking in it. There are best practices, but nothing you can’t find in a number of sources from books to the internet (just be careful which sources you’re using).

There TOTALLY IS aircraft wire, aircraft aluminum, aircraft rivets and aircraft engines…Just take any old regular product, multiply the price by 10 or 50 times, and voila, aircraft ‘fill in the blank’

My first drawings passed with flying colors (since I taught myself)(when I was 12 in 1972)(to design a hang glider) and now I is a Dasign Enginmaneer, and a SolidWorks esspert.

My claim to fame is I have all four of the Tony Bingelis books at the end of the article in my aviation library.

A well thought and well written article. Thanks.