This was going to get ugly.

Crossing southern Louisiana in the middle of the afternoon in late May is never pretty. Today was going to be no exception. Thunderstorms were popping up everywhere, and a long occluded front about 100 miles north of the coast stretching from Texas to Florida was holding the elements of convection right in the cooking pot, feeding the boiling cloud masses and generating some small but strong storm cells. They were everywhere, and there was no way around.

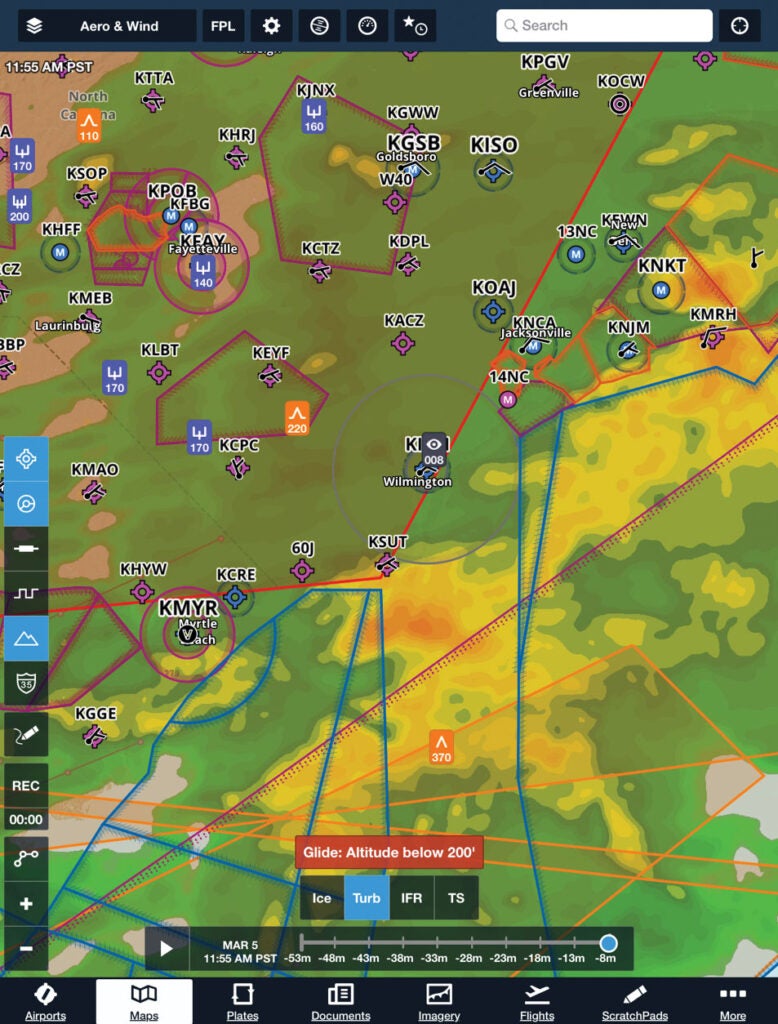

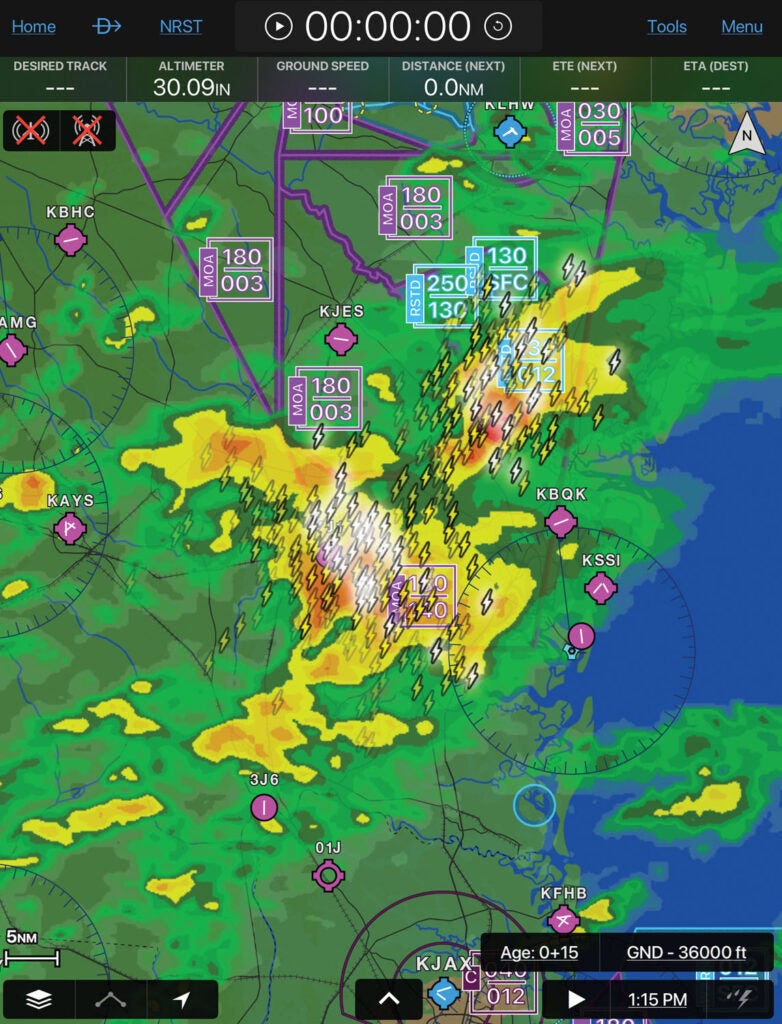

Headed west, as low as we dared to go, it was clear that we didn’t have much choice but to press on. The cells had us surrounded and the line ahead was narrow but strong. The NEXRAD radar was showing about 3 miles of red surrounding a mile of a darker shade I had never seen before, and the gradient from green to yellow and into the nasty colors was extremely tight.

I had Louise close in trail and we pressed on through. As we hit the line, the visibility dropped to near zero and the water was cascading so hard off the windshield that we might as well have been in a submarine.

Oh, wait a minute—you didn’t think I’d be stupid enough to be doing this in an airplane, did you? No, no, no…this was a surface job.

It was about 10 years ago and XM satellite weather had just become a thing. I was “commanding” a 26-foot diesel rental truck and Louise was chasing in her Toyota 4Runner with Karst the malamute as copilot. We were moving her household things from Washington to Houston, and I had never really played with the Garmin GPSMAP 396 and XM on a road trip before.

This was an interesting opportunity to use it to actually penetrate some weather—safely, with wheels on the ground and the ability to slowly coast down to whatever speed was necessary to stay safe—and see how the depictions on the screen correlate to the actual weather. If you are flying with NEXRAD (either XM or ADS-B) a lot, especially in the Thunder Belt, you might do the same thing—take it along on the road and see from the ground what you never want to see in the air! Today, you can take your favorite app along but be aware that some weather depictions are different when using an internet source than you will see from an in-flight ADS-B feed.

Learning the Limitations

Recently, the FAA has published notes on the limitations of using datalink weather in the cockpit, and it is worth reiterating that there are indeed real-world limitations. While I am convinced that having graphical weather information in the cockpit is the greatest single advancement in cross-country aviation safety since the invention of the wing, I go out of my way to also make sure that people know that, just like any tool, you have to use it with some smarts—and know when you can’t rely on it.

Whether your in-cockpit weather is delivered via satellite or through an ADS-B connection, the data you receive is going to be delayed from real time. I like to point out that while NEXRAD weather radar is great, the rest of the data available is just as valuable—but you have to understand its limitations.

For example, I like to use the downlinked METAR data when flying first thing in the morning. Airport observations frequently show low ceilings and poor visibilities between sunrise and mid-morning because of narrow temperature/dewpoint spreads—this is just the “nature of nature.” So watching the weather improve as the morning goes along is reassuring when I am covering long distances. But you have to remember that METARs are generally issued once an hour and much can change in 60 minutes. Dialing in nearby AWOS stations is a better way to get a handle on fast-changing trends—at least those within radio range. The METAR data, therefore, needs to be looked at along with the clock—and the best time to check it is just after the top of the hour when all the latest reports have just come in and have made it to your device.

Winds aloft data is another good example of “make sure you know what you are looking at.” The info that we get through the data links is forecast wind data, not what is actually going on. Winds aloft forecasts are probably some of the greatest works of fiction in the entire weather universe, no matter how you get them (preflight or in flight), and while they will give you a reasonable idea what might be happening if you were to change altitudes, it is rare that you get the whole story without actually going up and snooping around. The advent of real-time wind data in the cockpit (available on most modern EFISes) can help much more than the forecasts that we all grew up with—and what we read off the screen tells us how reliable the forecasts really are.

But let’s get back to NEXRAD and that trip along Interstate 10. Thunderstorms are the very definition of dynamic weather events. They grow and change rapidly—and the faster they change, the more violent they tend to be. When faced with a wide area of precipitation or building precipitation in our path, it is important to look first to the age of the data on our receiver (usually indicated in minutes since the last image was received), and second to have a look out the window to see if what the screen tells us makes sense with what is actually out there. The minutes shown on the display indicate the time since the data was received—not from when it was generated, and numerous technical issues can cause delays of several minutes. My rule is that if I don’t see a significant change in the picture with each update, then perhaps the weather is outpacing the delivery of the data—a big red warning flag that tells me that it might be time to choose another plan.

Because I tend to rely on out-the-window cues to help confirm what I am seeing on datalink weather, I am not inclined to be in the clouds with dynamic weather (such as thunderstorms) shown on the radar. Once you find yourself in the clouds, the ability to judge the validity of what comes over the link is diminished considerably. Most light airplanes—no, all light airplanes—are going to come out on the short end of an encounter with any thunderstorm worth the name, and that’s a risk not worth taking. Therefore, I stay out of the clouds when convective activity is present, except for unique circumstances, such as with widely spaced cells with little dynamic activity or change observed over a long period of time.

This is why a trip with a portable NEXRAD on the ground can be so valuable—you get to look at the weather on the screen, then actually penetrate it and see what it’s like. And then ask yourself if you’d like to be inside that same weather up in the air! This is probably the best lesson you can get on how well the system actually works.

Weather Strategery

So you’ve “penetrated” the weather safely on the ground and learned that you probably don’t want to find yourself in anything more than a yellow return. How do you apply this to your everyday flying? Well, obviously, make sure that you stay out of the orange and red, right? It might seem obvious, but several pilots every year still manage to come out of the bottom of thunderstorms without wings.

So let’s talk strategy. The biggest thing that XM gives you over actual airborne weather radar is “the big picture.” With airborne radar, you get to see what is directly ahead of you—and only as far as the power of the radar set can penetrate. With NEXRAD data, you can see not only what is ahead, to the sides and behind you—you can also see what is beyond what is ahead of you. Being able to see to the sides and behind is a great way to make sure that you are never cut off from a safe line of retreat. Seeing beyond what is directly ahead is a good way to tell if going on is even worth it. If you are facing a small area of cells and/or precipitation ahead of you, but have clear spaces between and nothing beyond, then you are probably going to be able to get through and continue on your way. If, however, you are looking at a wide area of weather ahead, something that extends for 50–100 miles, you are probably going to get yourself in trouble if you press on. Large area masses of convection generally get worse before they get better and, once inside, you are unlikely to find a safe way out.

When faced with weather ahead, I operate with a “safe retreat” rule. I always want a straight course to an airport that is clear of anything more serious than green returns. I don’t mind snooping up ahead a bit as long as I can turn around or deviate to the side, where I can get on the ground to sit things out. While this might seem a little limiting, the fact is that if I can’t find a precipitation-free route around or through an area of convection, then I probably don’t want to be in there with a light airplane—it can just get too bad too quickly. One useful tool in the NEXRAD data is when you start seeing actual “cells” being depicted. Red radar returns are bad enough, but the little cell depictions are the weather service’s way of saying, “Hey dummy, you really don’t want to go here!” Likewise, lightning data is another “keep out” sign that I always try to observe, especially because I am depending on the electrical equipment in the airplane to keep operating and feed me the information I need to stay out of trouble.

Gulf Lessons

So what did we learn on that day on the gulf coast? Well, by direct observation we learned that when the rain gets into the red zone, it is the kind of stuff where the road is flooded! The kind of rain where it is so heavy that wipers are useless at 30 mph. I am guessing that at 160 knots, it might put so much water into the intake of a “snout cowl” RV that the engine just can’t get enough air…

We learned that tight gradients are really bad! Green is the kind of rain that rinses the airplane but doesn’t get it clean. Yellow is something you want to stay away from, but the occasional foray probably won’t scare you too badly—so long as there isn’t any red next to it. If there is red in the cell, I am not even going to get into the green—there is too much electrical charge in the convection. I have seen lightning bolts in the clear blue sky surrounding a tight storm—no thanks! The narrower the bands leading into the red, the faster the storm is developing, the more severe it will be. Finally, once you start seeing the XM identifying actual “cells” rather than areas of rain, it is time to go for an alternate plan, stay well away in the clear air and watch from afar.

I have always enjoyed watching thunderstorms, but I like doing it from a fairly safe place. It’s a pain to drive in that weather (in this case, we were motoring on the Atchafalaya Bridge, 18 miles with no way off, or we probably would have pulled over), but completely unsafe to fly in. It is unfathomable to me what goes on in the minds of pilots who think they can fly through red radar returns—storms don’t last that long, they will go away, and you can get through later. If you don’t believe me, take your XM or internet-fed app like Garmin’s Pilot or ForeFlight on a road trip and go “penetrate” some storms. You’ll be a believer and, more importantly, a survivor.

“If you are flying with NEXRAD (either XM or ADS-B) a lot, especially in the Thunder Belt, you might do the same thing—take it along on the road and see from the ground what you never want to see in the air!”

Can you get ADS-B weather on the ground?