Early in my flying career, I had the good fortune of securing a part-time corporate gig in a new-to-the-boss Cessna 340A. My first trip involved flying the boss from Salt Lake City to Scottsdale, Arizona (KSDL). After an overnight there, the plan was to fly early the next morning to Tucson (KTUS), where he would work a full day, then we would fly back to Scottsdale for the night. On the third day, the boss would work a full day in Scottsdale and then we’d return that evening to SLC. Easy peasy.

The first leg was uneventful and the boss was quite happy with his new ride. I checked into the Scottsdale hotel and had a light brunch. An hour or so later, I was struggling with some early symptoms of gastrointestinal distress. Another hour and the dump valves were open and active fore and aft. A pinch test on the back of my hand confirmed that I was dehydrated. I procured some Gatorade from the gift shop but couldn’t hold it down.

In between trips to the porcelain altar, I kept running scenarios in my head for what to do for the flying schedule early the next day. Tucson was only about 45 minutes each way but that was still beyond my range at the moment. I didn’t want my boss to have to drive on the first trip with his new airplane.

I pulled out a phone book and started calling local charter companies to see if I could find a qualified replacement pilot. I had several offers to fly the trip but only in their own aircraft. Finally, one operator gave me the name of someone he knew would be ideal. I was able to reach the individual and not only was he eminently qualified but available and willing to take the trip. When I informed the boss of the situation, he took it about as well as could be expected. He was apprehensive but appreciated my initiative to address the situation.

I had a bad night physically. But having the flight taken care of brought a lot of stress relief. As much as I wanted to feel better, I worried that being totally fine the next morning would prove that I had overreacted. Such was not the case. In the end, I recovered in time for the last flight back home, only to be regaled ad nauseam about what a great guy the other pilot was. In a way, I was lucky to be as sick as I was because it forced me to decline the flight. I’ve often wondered what I would have done had I been “less sick.”

Software, Hardware

In this magazine we talk a lot about hardware, which is appropriate. However, since every flight has an operator, on occasion it is important to also refresh the human factors in aviation. Like our machines, our bodies and minds suffer aging issues, wear and tear and even breakdowns. We require constant and diligent care and maintenance.

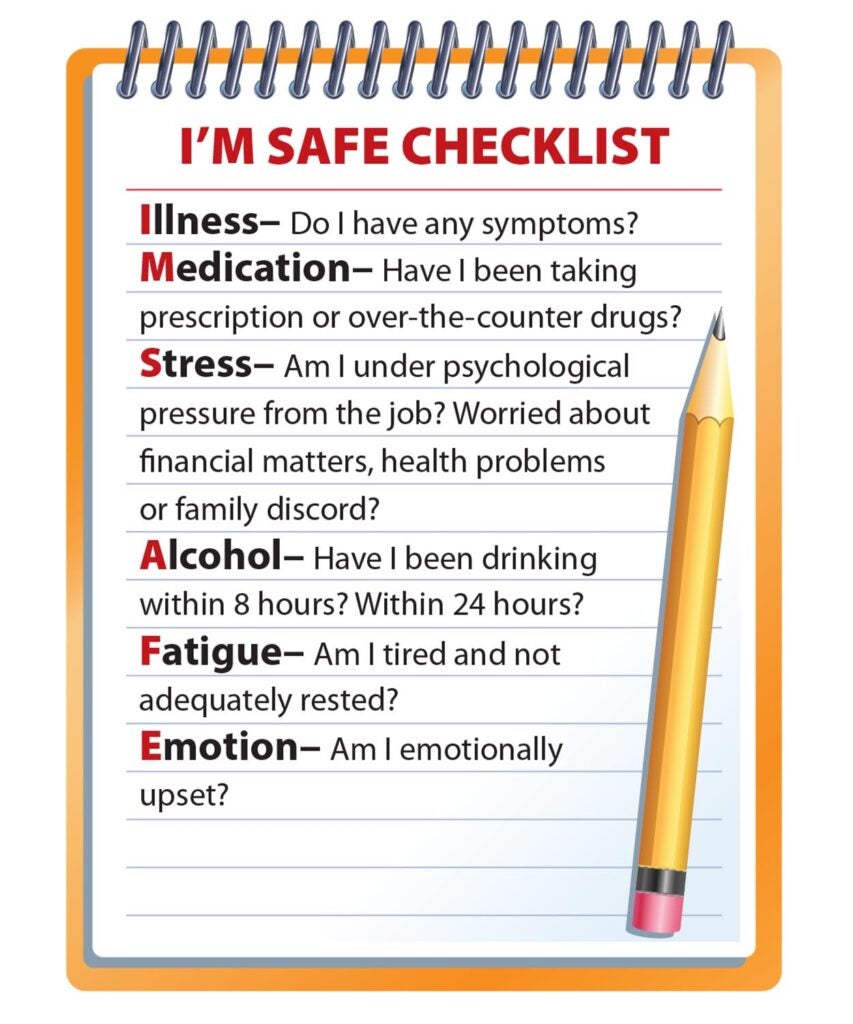

To provide pilots with a checklist to help determine fitness for flight, a coalition of advocacy groups, unions, operators and federal administrators created and promoted a mnemonic checklist commonly referred to as IMSAFE, which is regularly reviewed in commercial recurrent training. The tool is referenced in various training publications as well as the Aeronautical Information Manual in the first section in chapter eight. Let’s take a quick review of each item in the acronym.

I Illness: Obviously, being ill can have a debilitating effect on a pilot’s ability to safely operate an aircraft. An illness can be chronic or acute; the latter can afflict before a flight, during a flight or “on the road” during a flying trip. Each pilot, commercial or private, has the responsibility to self-assess their fitness prior to every flight.

M Medication: As every pilot knows, there is a very short list of medications approved for use during flight and a long list of those that are prohibited. You can find more information in an FAA brochure titled “Medications and Flying.” A good source for further information is your Aviation Medical Examiner (AME). The short version is that sedating antihistamines, muscle relaxants, some dietary supplements, pain medications, “pre-procedure” drugs and certain sleep aids are verboten. Wait times, the period after consumption of various sleep aids before the pilot is deemed safe to fly, range from 24 to 72 hours.

S Stress: Stress is a biggie. Everybody encounters stressors and we all can react differently at different times. Stress distracts. Stress debilitates. Stress kills.

I will never forget one night on an arrival into San Diego where we flew over a wooded canyon in the foothills to the east and my first officer watched in horror as a recently erupted fire overtook his own home along with several of his neighbors’. Being in the area was actually a blessing as he was pulled from the trip upon landing to focus on what was most important in his life at the moment.

Pilots are trained to focus and prioritize flying tasks with a stiff upper lip and stoic resolve but we’re all human and some of the most dangerous stressors are those that are repressed. Stress is much more than emotion and can have actual physical effects. The cockpit is no place for a significantly stressed pilot.

A Alcohol: From the very beginning of aviation, there has been a long association in pilot culture and tradition of vigorous consumption of adult beverages after flying. It is what it is and can be seen in festive abundance at aviation events including AirVenture, where, to borrow from Lloyd Christmas, “The beer flows like wine.” The overwhelming majority of imbibers act responsibly. However, we all have witnessed the destruction that can result from the actions of the irresponsible minority and we all eventually pay for it directly or indirectly. Containment of the problem starts with policing ourselves and includes watching out for each other.

F Fatigue: Fatigue is also a killer. Simulator studies have shown that sleep deprivation has practically the same effect on flying skills as alcohol and both advance in gravity on a similar linear scale. During the latter part of my airline career, we actually had the contractual provision to call in fatigued and be released from duty with full pay, which was something that would have been unimaginable earlier in my career.

It has been said that if caffeine were outlawed commercial aviation would collapse, but even caffeine can only help so much and too much too late in the day can affect subsequent sleep and fuel a vicious cycle of cause and effect.

Ensuring proper rest and limiting flying exposure in the face of fatigue, even if the destination has yet to be reached, is an inherent part of assessing and maintaining fitness for flight.

E Emotion, Eating, Environment: The last letter of the IMSAFE mnemonic is a curious one. A search reveals that the official FAA list shows “emotion” but other lists by training and/or advocacy groups use “eating.” Rather than choose between the two, I have decided to add a third, “environment,” and will briefly address all three.

Emotion is closely related to stress but deserves its own attention. I will never forget the last time I spoke by phone to my mother. She was hospitalized while recovering from surgery but she was feeling much better and was set to be released later that day. My chief pilot had already pulled me from a couple of trips to attend to her situation but now that she was on the mend, I was set to return to work. I told her that I would stop by to see her on my way to the airport and my wife would then take her home.

A couple of hours later, I arrived at the hospital just as her attending physician ran up asking me, as her medical power of attorney, to waive her signed DNR so that they could intubate; without it, she would die within minutes. I signed the form, in full uniform, about an hour before I was scheduled to report at the airport 20 minutes away. Obviously, I didn’t report for work and the company was understanding once I explained the situation. I spent the night at the hospital and she passed the next morning without ever awakening.

Over the course of my career, I have flown with a pilot who came to work carrying freshly served divorce papers, one who had a teenage son commit suicide days before, one who had spent the morning moving out of his repossessed house and several others facing similarly horrible situations. In more than one case, the individual justified coming to work as actually being preferable to staying home. Call me skeptical. They say to never make important decisions while under the effects of grief and I would include taking the controls of an aircraft under that recommendation. The same holds for anger—avoid flying while “pissed off.”

Eating. Obviously being properly nourished and hydrated is also part and parcel to maintaining proper fitness for flight. I always carry drinking water in my airplane regardless of the length of the trip. Skipping meals or trying to sustain yourself from the vending machine at the FBO while trying to make a schedule may seem the right decision but you’re leaving yourself vulnerable to fatigue and other factors that make this choice a poor one.

Environment. Two human physiological issues related to the cockpit environment are hypoxia and carbon monoxide poisoning. I know people who have perished from both. The two insidious killers are both related to oxygen, with hypoxia being a lack of oxygen and CO interfering with the body’s ability to absorb oxygen. Both provide an early false sense of security. Both situations are preventable with proper preflight planning along with in-flight monitoring, awareness and immediate recovery if necessary.

The items of the IMSAFE list are both individual and in many cases interrelated. A realization dawned on me while constructing this treatise that some poor sot somewhere probably managed to check every box during the same flight.

Healthy “liveware” is as important to flight safety as healthy hardware. The FAA offers some basic educational tools but administratively puts the onus directly on the shoulders of the operator to ensure fitness for flight. Use IMSAFE to BeSAFE.