Way back in the previous century—closer to the middle of the century than the end—I learned that the secret to cross-country navigation was a carefully prepared and highly detailed waypoint log. You started by laying a paper chart out on the floor and drawing a line between your departure point and destination. You then looked for (hopefully) recognizable landmarks about every 10 or 15 miles and put a little tick mark abeam them on your line. You then built a navigation log that listed the landmarks and the distance along your line to each one. What followed was a series of calculations that gave you the time and fuel at each point. When you flew the trip, you checked off each waypoint as you recognized it and kept track of your times to see if you were making or losing time and fuel. It worked well in a J-3 Cub and gave you something to do besides watching the trucks pass you on the highway below.

Fast-forwarding nearly 50 years, I have to admit that I haven’t kept a paper navigation log for many decades nor have I drawn a pencil line on a paper chart. Truth is, I haven’t bought a paper chart in so many years, I no longer know how—or if they are even available! Navigation has changed a lot in the meantime, mostly due to technology that helps us to fly smarter, not harder.

And Today

So how do I fly cross-country today? I start by making sure that the navigation program on my iPad is up to date. I use ForeFlight, my wife uses Garmin Pilot…anything will do and there are free options if you don’t want to pay the $100 or so per year. (There is inflation even here, as the latest ForeFlight Basic is $120 a year and the Pro Plus is twice that. Garmin’s Pilot starts at $100 and goes to $180 for the upgrade package.) Still, when I consider that I used to spend $600–$700 a year for paper subscriptions to IFR and VFR charts, it’s all a bargain.

I’ll admit that with multiple airplanes in our hangar, I don’t keep all of the EFIS-embedded databases up to date—yes, some are free (while others cost), but it’s not the money—it’s the time it takes to keep five different brands of EFISes up to date that makes me decide on what I bring to the cockpit.

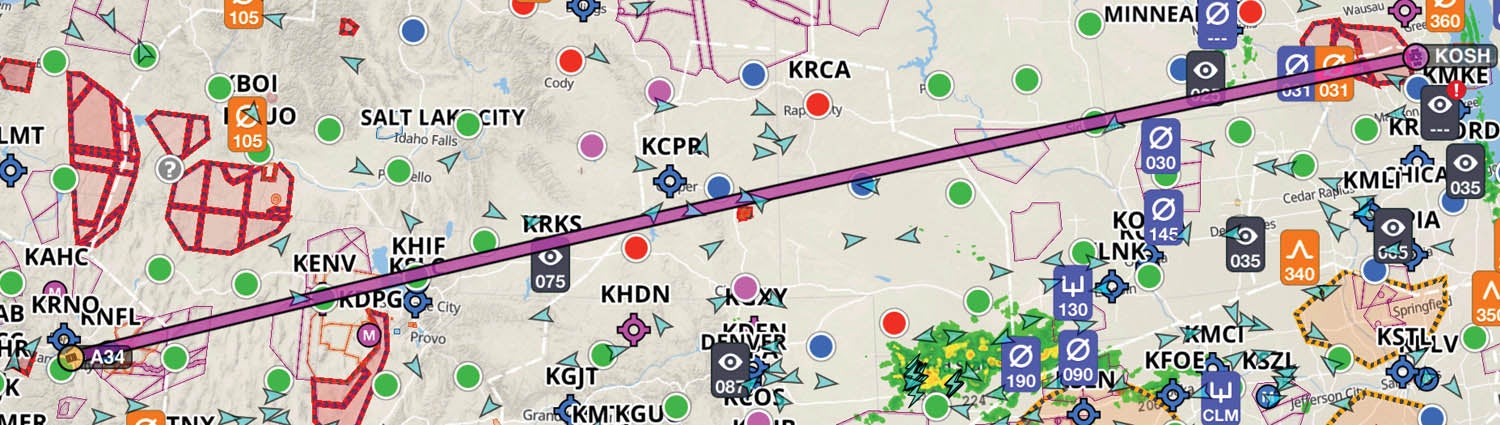

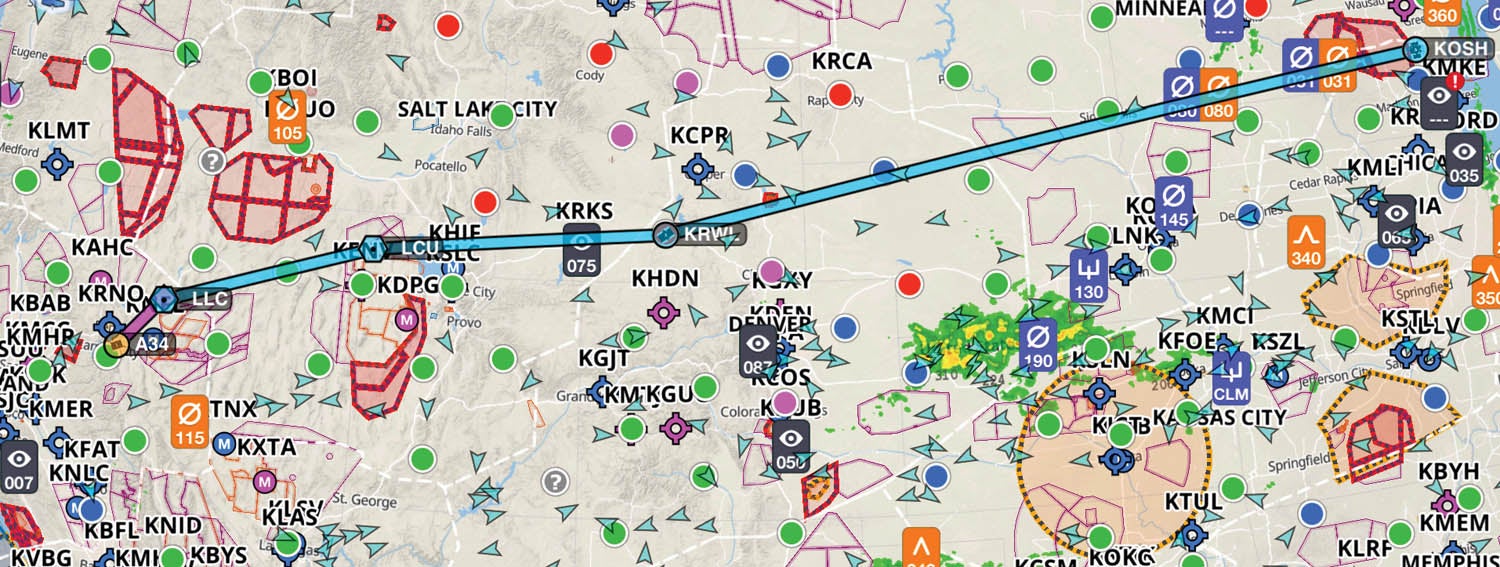

So let’s take a typical cross-country trip—my home near Lake Tahoe to Oshkosh, for example. Yeah—it’s a long trip, with multiple legs. We’ll need some fuel stops, and who knows what will happen with the weather? But rather than a complete, buttoned-down plan (that will be wrong as soon as the heat of the day starts shaping the atmosphere across the Great Plains), we’ll make a general outline, one that can be molded and reshaped as the day goes on. But I start in a similar fashion to that old line on the map—I pick the departure (A34) and destination (KOSH), and let ForeFlight draw a great-circle route.

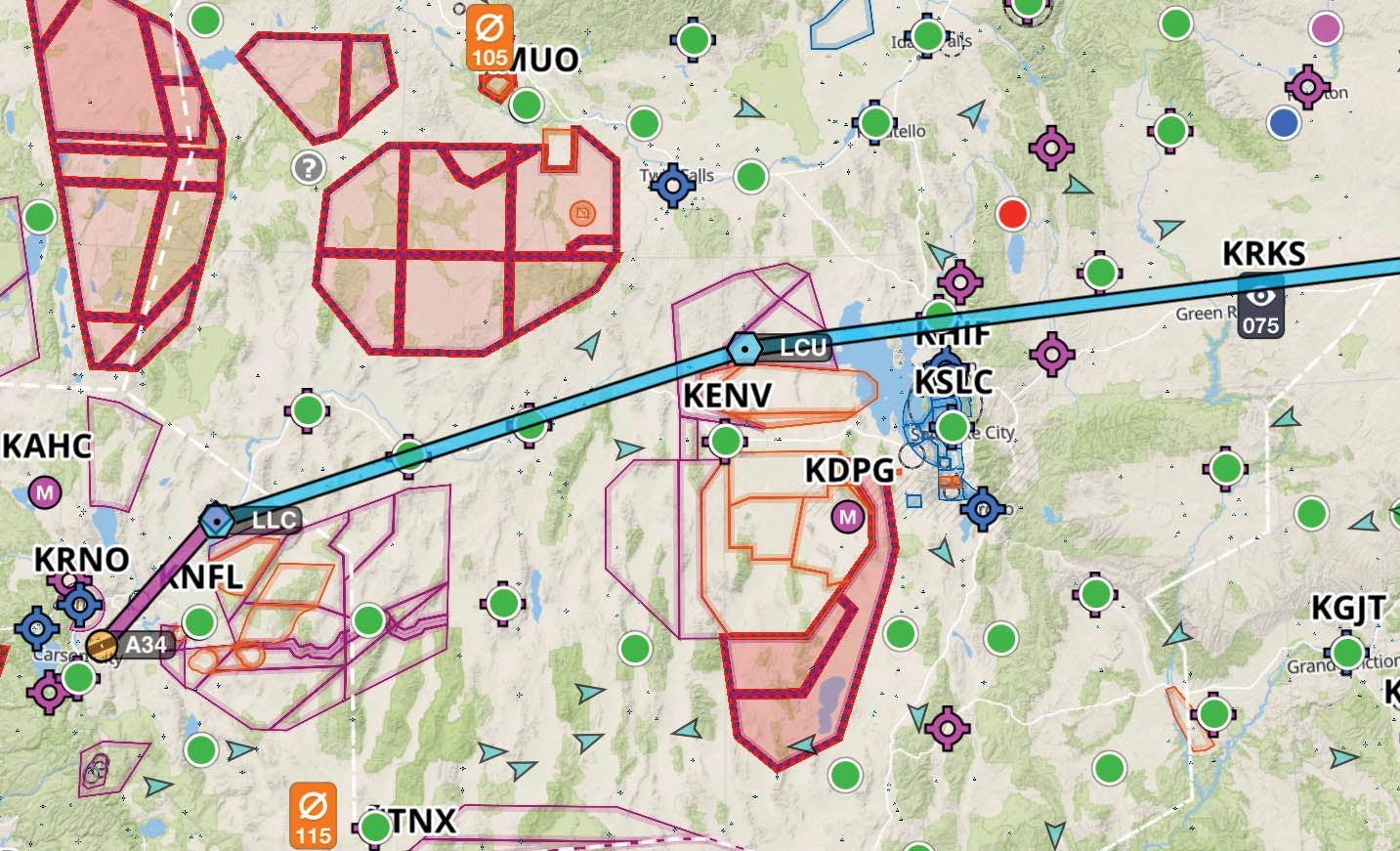

Now I know I’m not going to fly that line—partly because there is restricted airspace in the way. So I start with “fixing” the route. I grab the line and drag it to various navigation points that will avoid the problem areas. That means deviating north around the Top Gun airspace east of Fallon, Nevada, which will also keep me clear of the big restricted airspaces of the Wendover region. I drag the line to the Lovelock (LLC) and Lucin (LCU) VORs, then from Lucin, I can pretty much go direct to OSH if I want. So much for route finding.

Gas Pains

Now let’s talk about fuel stops. Yeah, I know—most folks need to stop for a potty break before they run out of fuel, but I personally hate losing all that cruise altitude, dropping down into the heat and bumps, then clawing my way back up. So I carry piddle packs and use them as needed. From a fuel standpoint, it depends on the aircraft. My long cross-country choices are usually the RV-3, RV-6 or RV-8. Flying them to dry tanks in calm air, the -3 will go 600 nautical miles, the -6 will go 700 and the -8 will make it 800. So let’s be reasonable and allow for reserves and wind. That makes the ranges 400, 500 and 600 nautical miles, respectively, for planning purposes.

Picking the RV-8 (since this is Oshkosh, and I need to carry a week’s worth of gear), I start by finding potential fuel stops between 500 and 650 miles. I don’t write them down, I just think about what is available and what the fuel prices look like. Eastbound, for this trip, that generally puts me about Rawlins, Wyoming, for the first stop—but I can easily stop at Rock Springs if the winds get grumpy or extend out to Casper or Douglas if I have great tailwinds and the weather pushes me north. Interestingly enough, the weather rarely pushes you south—and if it does, you’re going to end up in Missouri for the night instead of Wisconsin. Weather moves northwest to southeast (generally speaking), so it is better to aim behind it rather than get bulldozed out in front. And I am also aware of some really short options, such as Wells, Nevada (very cheap fuel) or Brigham City, Utah, if I find that I want to have full fuel before setting off across Wyoming for some reason, such as picking my way through weather.

Once I have picked up fuel at around the 600-mile point, I’ll do similar planning for the next stop, and the next (if needed). For this example trip, that is going to somewhere in eastern South Dakota or western Iowa/Minnesota. I look at fuel prices and NOTAMs for a variety of spots before I set out—but I am not married to any particular airport. And I’ll choose a final spot somewhere before Oshkosh if this is AirVenture time—I like to arrive with enough fuel that I don’t have to buy any at the show, so that I have more than enough to get to a good stop on my way out.

No Commitments

Now I have not committed to landing at any of those places I mentioned. Generally speaking, while I have my planned fuel stops in mind, what happens next is that I launch and once I am at cruise, I look at winds, weather and estimated fuel at all the waypoints en route to decide where I am really going to stop. All modern EFISes will show you estimated fuel at each waypoint in the flight plan based on real-time usage and current groundspeeds. The trick is simply to put in enough waypoints so that you can scroll down the list and find where you’ll be when you hit an hour’s fuel (or whatever number you’re comfortable with) and make that your destination.

If weather gets in the way, deviate left or right—based on how you can get behind the weather—then add appropriate waypoints to the flight plan so that you can track where the next stop should be. This real-time, in-flight planning is made possible by modern electronics, good software and in-flight weather.

A couple of safety tips when flying this way. First, determine in advance what your minimum fuel state is going to be—how little you will land with—and don’t change those rules in flight. Second, don’t forget to check NOTAMs for a planned fuel stop far enough in advance that you don’t paint yourself into a corner if you get there and the runway is closed due to resurfacing. Third, ask yourself what you’re going to do if your weather information stops updating. While I advocate keeping your options open on a long cross-country, I also advocate making sure that those options are real!

I call this method of flying real-time progressive planning—you have an overall plan and make up the details as you go along. It makes it harder to tell someone where you’re going to be stopping in advance (because you don’t know yourself), but it is a flexible and efficient way of crossing the country. You still have a plan—it’s just not the way we did it in the old days of paper logs and charts. And that’s OK.

Images: Foreflight screengrabs.

I appreciate the article, well written and useful.

Well written article, but going to VOR’s is so 20th century. I have a similar method for planning VFR cross country journies but I go from airport to airport. And more and more VOR’s are decommissioned or schedule for shut down. Thanks.

I agree wu=it’s youWeston – we don’t use VOR-to-VOR navigation either….it just turns out that in this specific case, the Airways (which go VOR-to-VOR) are plotted to specifically avoid the restricted areas, so they are convenient waypoints. What is nice is to pick waypoints (VOR’s or Intersections) that you can quickly type in to your navigator, so you don’t have to worry about Lat/Lon user-defined waypoints.

Very interesting, Thanks.

Do you file a flight plan with this method? And update it over the radio as you go?

Regards,

Sven

Honestly – no. I’d have no idea how you’d do that, since you don’t know where you’re going to land, or how long you’ll be. But in today’s AD-B world, and with someone else knowing I am in the air, and my basic plan, rescue isn’t that far away. Of course, you can’t really fly IFR with this method, so an IFR flight plan isn’t applicable.

I hold 14 FAA certificates, and I only filled out a paper navlog for 3 of them (PVT airplane, PVT Helicopter, Instrument Helicopter), and mind you I trained almost entirely in steam gauges and no tablets. Navlogs, as taught, with overly detailed information are nearly worthless and I can prove it (not here in this particular comment though). After my first instrument rating (3rd rating at the time), I vowed to never fill one out again and have kept true to that. That checkride proved definitively the wasted effort and pointlessness that is a paper navlog. Nothing wrong with writing down waypoints, distances, and a rough expected time, and heading and such, but nothing more is really required. I was easily able to hit 40+NM legs within 1mile accuracy using nothing but dead reckoning (no VOR or GPS) before getting my very first PVT pilot license. I was taught “old school” navigation techniques by my CFI that were extremely accurate even on long legs and required almost no planning. And the tricks I use for VFR cross country planning work 100% the same for IFR flights too.

I love Paul Dye’s well written, plain speaking, to-the-point articles! Always great stuff, and I always appreciate his perspective.

I’d taken a long hiatus from flying- there were no GA EFIS airplanes when I earned my tickets last century. There were no GPS devices for us either. So it was steam gauges and paper charts. I flew (from San Jose, CA) all over the country in my Debonair, often IFR, and often at night, using that method. Oh, and no autopilot. So, I knew nothing else, and was comfortable. (Well, IFR at night over the Sierras in a single doesn’t exactly give one the warm fuzzies…) Then the long hiatus…

Fast forward to a few years ago, I bought an experimental (Thorp T18,) installed modern EFIS panel, A/P, IFR Navigator, and flew it from Sacramento to OSH this past summer- using the same method as Paul. I’m STILL trying to wrap my head around the idea of no paper charts, and “what happens if the electrons quit flowing.” But boy, it was sure easy and convenient.

I can’t quite say I’m more comfortable with this new stuff- but that will change as I gain trust in the reliability of all the electronic technology. It’s clearly far, far superior to the “old days!”

Thanks Paul, for sharing your thoughts and stories.