Quite possibly, your eyes glazed over a bit when you saw the title of this article. Quite possibly, you’re poised to skim forward a few pages and give this article a pass.

I wouldn’t blame you.

Aircraft fires—both after an accident and, especially, in flight—have never been pilots’ favorite topics. It was especially feared in WW-I combat, when the lack of parachutes meant either burning to death in a long fall or a suicidal leap to avoid the flames.

Things haven’t really changed. Just 20 years ago, a flaming homebuilt fell to Earth. The pilot’s body was found several miles away. It is believed he jumped to escape the fire (NTSB Accident ID: SEA99FA113).

Our other fear, of course, is our homebuilt’s wreckage catching fire after a crash—especially if we’re trapped inside.

How often does it happen? What can we do to minimize the chance of it happening and maximize our chances of survival?

In Flight

If there’s a fire in a car, you escape by stopping the car, undoing your seat belt and diving out. Not necessarily in that order, either.

But—without a personal parachute—the situation is far different in an aircraft. You’re minutes from safety, and diving to the ground can fan the flames.

The main question you have: How often does it happen?

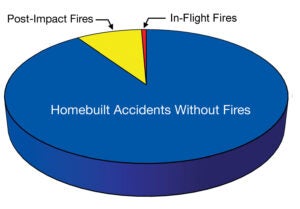

Figure 1 should provide some reassurance. In-flight fires are relatively rare. Over the 20 years covered by my homebuilt aircraft database (1998-2007) I found just 29 cases of in-flight fires. All but two were fixed-wing aircraft.

As one might expect, fuel leaks are the main source, with oil-fed fires coming in second. Electrical issues are in the third position. Sadly, we don’t know the source for over a quarter of the cases, usually because the systems were destroyed.

One curious aspect is that while about quarter of all homebuilt accidents involve composite airplanes, nearly half (13) of the in-flight fires affect composite aircraft.

Does this mean anything? Sure, composites are more flammable than aluminum, but wood airplanes will burn, too, as will fabric coverings (though modern covering materials are less flammable than WW-I-era dope and linen). There were only a few in-flight fires affecting fabric-covered or wood airplanes.

But the overall construction material doesn’t necessarily establish what’s wrapped around the engine. In-flight fires almost always start in the engine compartment, and fiberglass cowlings are very common regardless of what the main structure is made of. It doesn’t seem like a fiberglass wing and fuselage would add significantly to the risk of in-flight fire.

A bit of good news? The fatality rate for accidents involving in-flight fires is less than you’d expect: Only about a third of the in-flight fire cases resulted in death. In nearly half of the accidents, the occupants were able to land and egress the aircraft with no more than slight injuries.

Post-Impact Fires

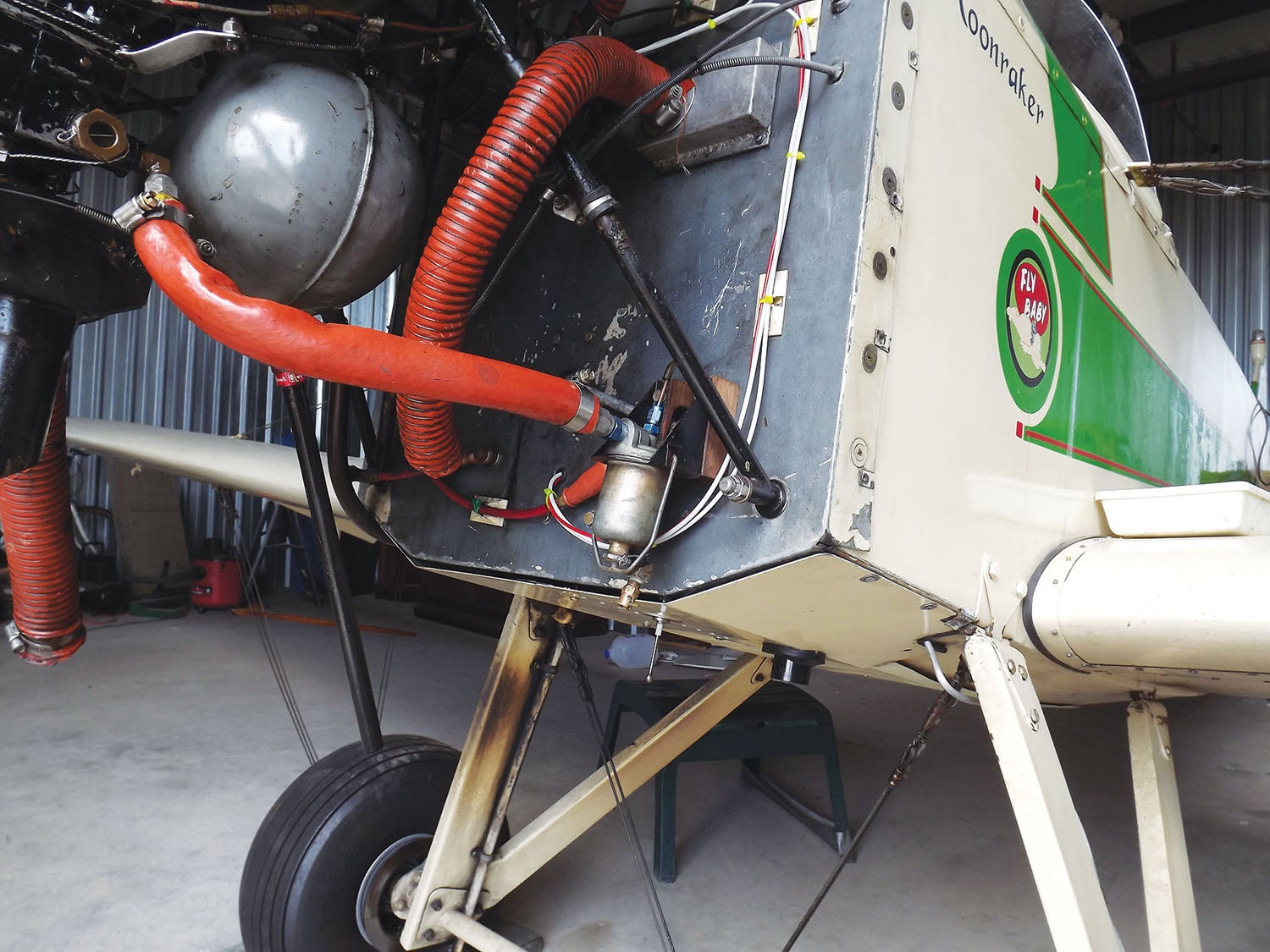

Back in 2002, a Fly Baby lost its engine on takeoff and cartwheeled. The pilot broke a leg in the crash, and was pinned in the wreckage. The fuel tank, located in the front of the fuselage over the pilot’s legs, ruptured. He was soaked with gasoline and unable to extricate himself from the aircraft.

No fire, fortunately. But this is a nightmare most pilots are only too conscious of.

So, what are the chances?

Let’s start with the probability of fire. From the NTSB records, about 10% of homebuilt accidents report a fire after impact. This is based both on an “aircraft fire” parameter in the NTSB database, as well as a manual examination of accident narratives to identify additional cases. As we saw in Figure 1, it’s a big slice of the pie, but still not all that common.

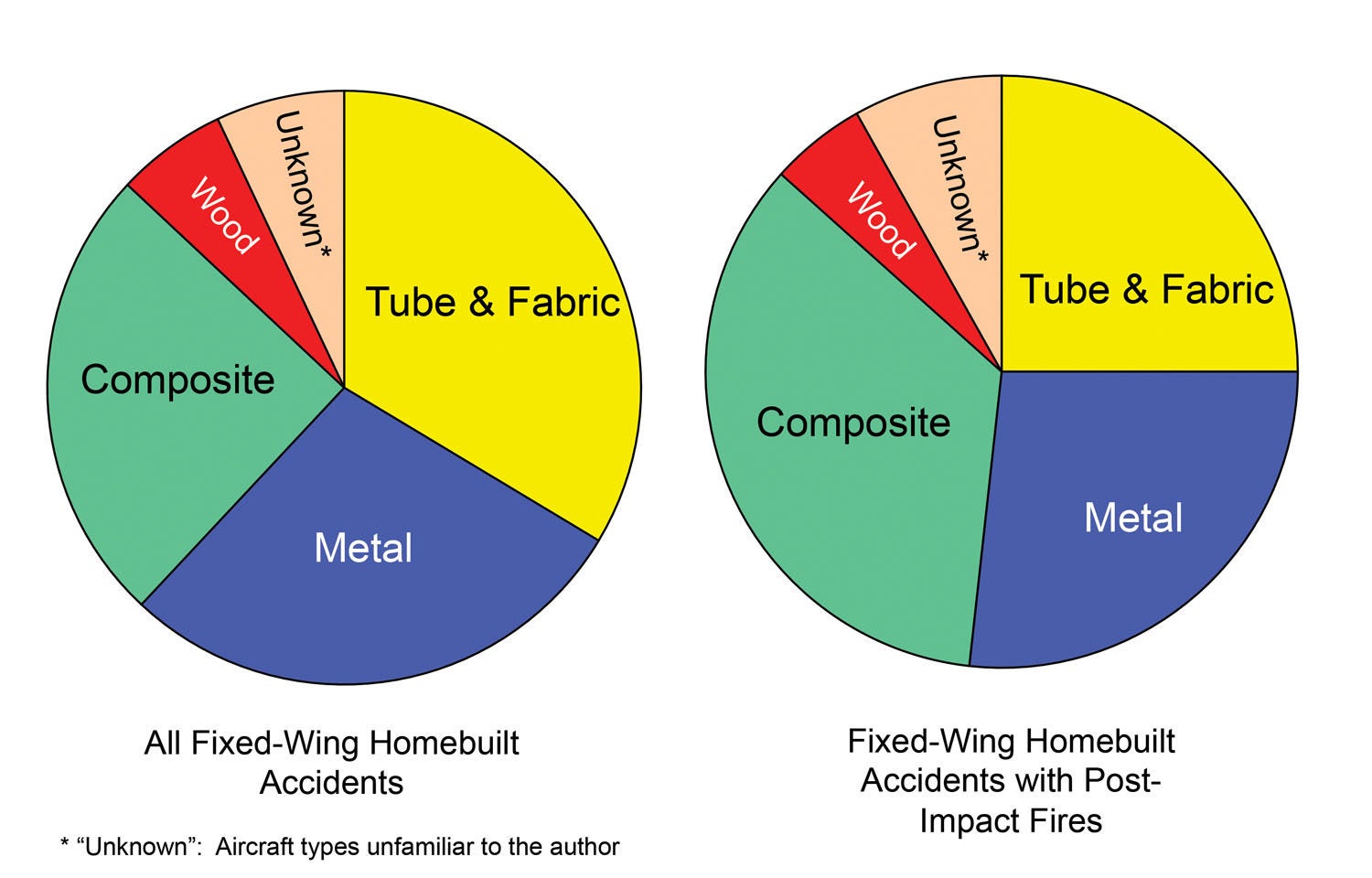

I took a stab at identifying the primary construction method used for 3428 fixed-wing homebuilt accidents from 1998 through 2017. Figure 2 shows the percentage of post-impact fires versus the construction method. (Note: “Unknown” in the figure refers to my unfamiliarity with the aircraft type, not that the NTSB was unable to determine the mode of construction.)

Again, composite construction stands out. Where the effect of the construction material may not be a great driver in in-flight fires (since the fire is usually primarily concerned with the engine compartment), composite materials do seem more likely to support fires after the airplane crashes.

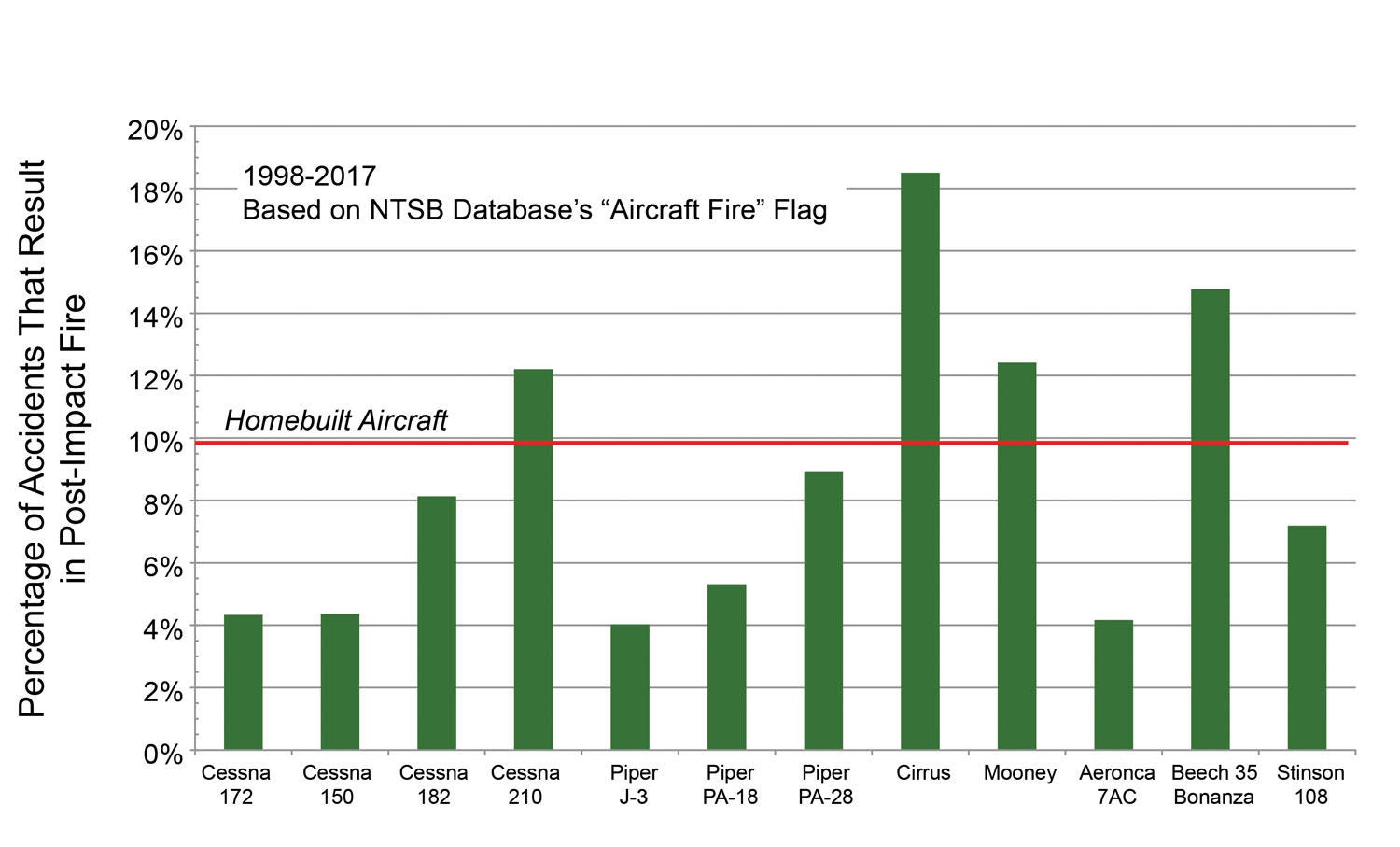

This is borne out when examining production-aircraft crashes. The all-composite Cirrus has the highest percentage of post-crash fires among a dozen small GA aircraft examined (Figure 3).

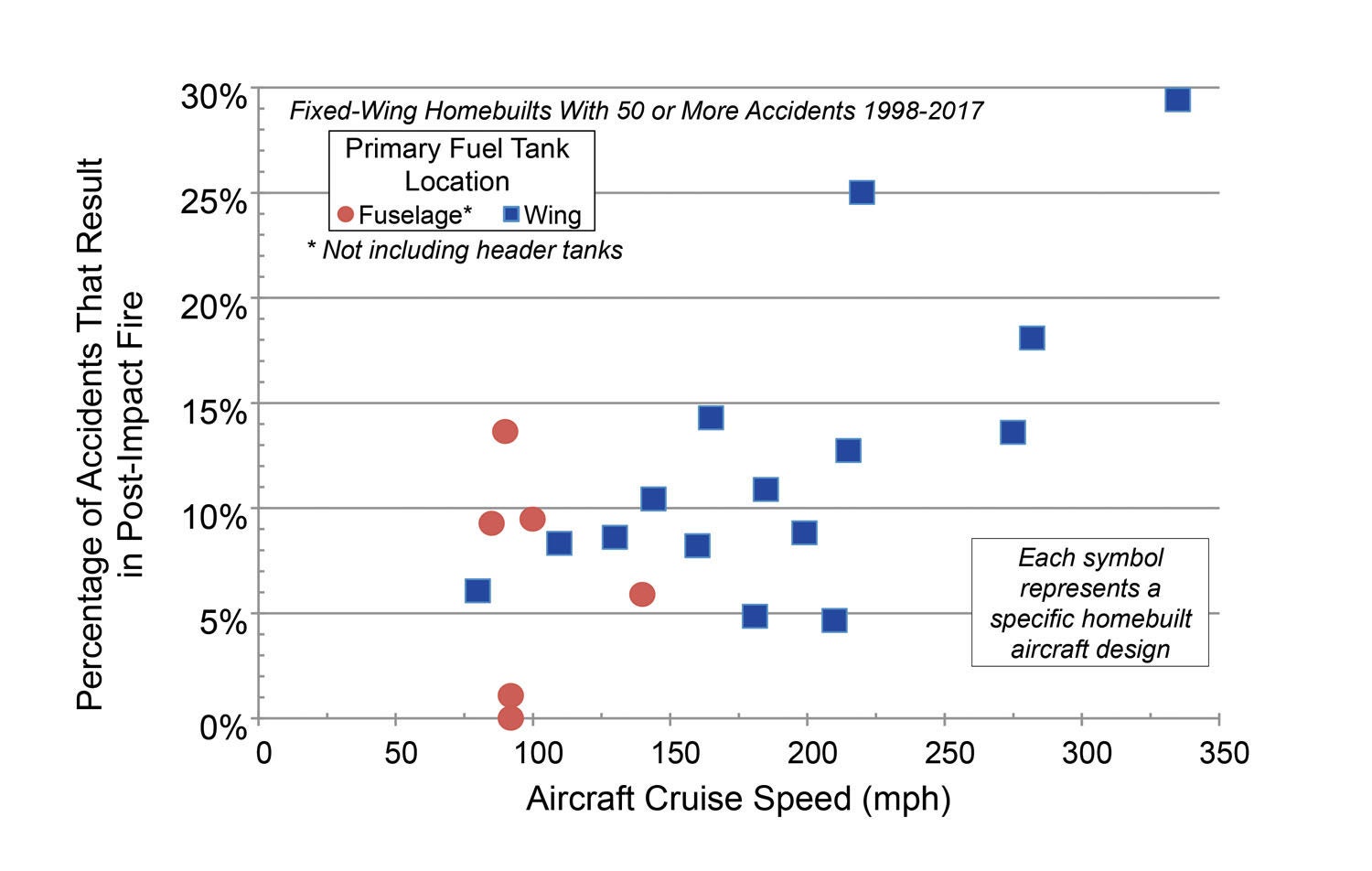

But it is important to compare aircraft of similar performance ranges. Burning fuel is usually a primary component of post-impact aircraft fires, and the harder the plane hits, the more likely the tanks will rupture. Hence, the faster the plane is going at impact, the greater chance of a post-impact fire.

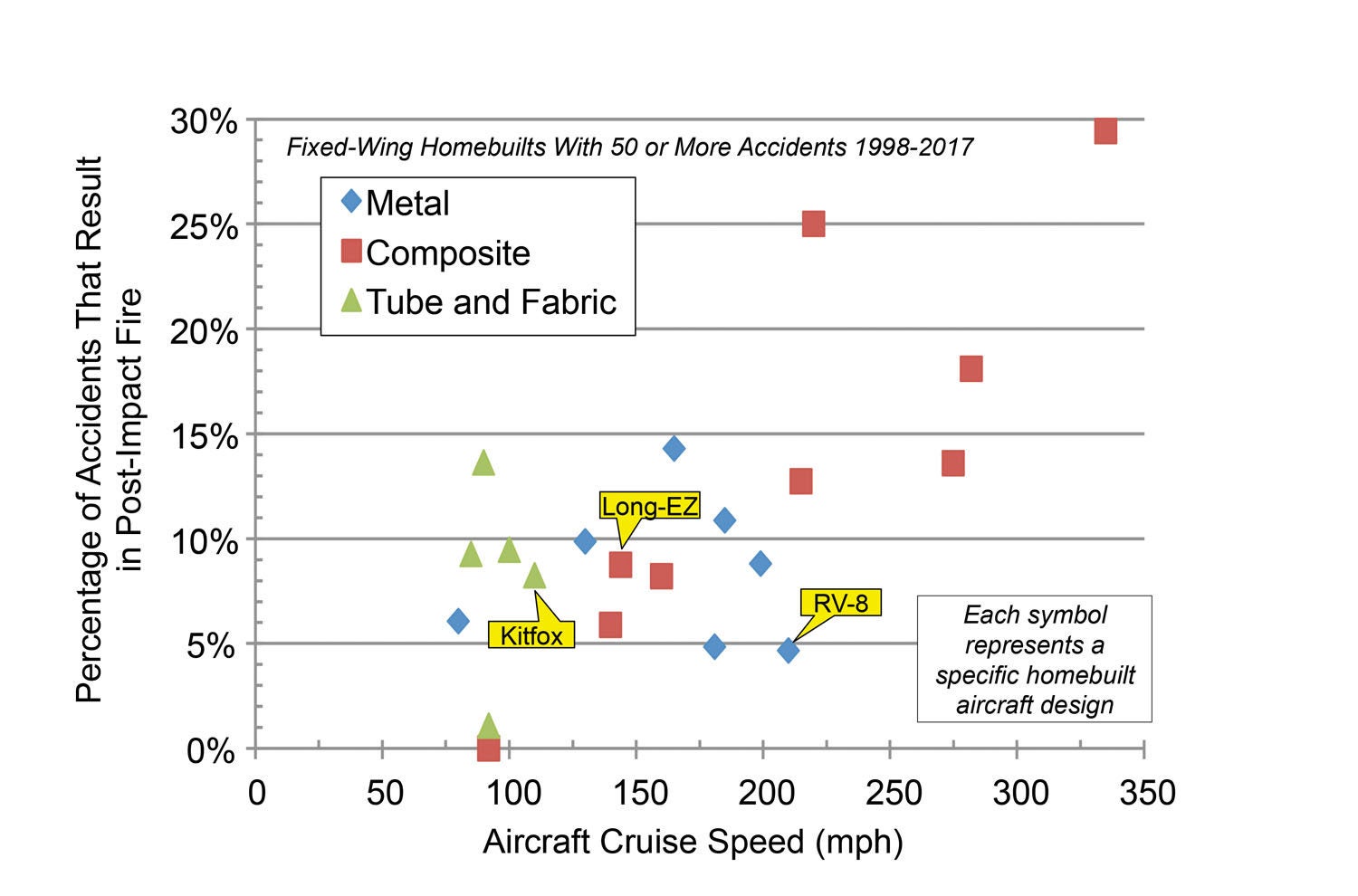

Figure 4 shows the percentage of post-crash fires for homebuilt aircraft versus the Wikipedia-listed cruise speed for the aircraft. While few airplanes actually crash at their cruise speed, it is useful as a metric for comparing the relative performance of the aircraft; most Pietenpol accidents occur at slower speeds than Glasair ones.

The figure also shows the type of construction. Again, composite aircraft suffer post-impact fires more often, but higher impact speeds probably have more effect.

(Which composite aircraft has no post-impact fires? The Searey. Seventy percent of its accidents were on water.)

Wrap-Up

We hate the thought of in-flight fires, but they’re rare—one or two a year, at most, across a 27,000-airplane fleet of homebuilts. That’s not bad odds.

What’s more, the survival rate for in-flight fires was surprisingly high. Reading the accident reports, the common factor in survival appears to be decisiveness—noticing smoke or flame, then immediately killing the engine, shutting off the master switch and heading for the ground.

Not to mention keeping one’s wits; landing successfully to permit rapid egress from the airplane.

The fatality rate in crashes that produce post-impact fires is grimmer. When a fire is reported in the NTSB summary, the majority of the cases involve deaths. However, the occupants usually expire due to the impact, not the fire.

The overall viewpoint looks better. From 2005 through 2017, thermal injuries or other fire-related causes were mentioned in the autopsy portion of NTSB reports in less than 5% of all fatal homebuilt accidents. And most included physical trauma as well, so the deaths were not necessarily due to the fires alone.

The first lesson: Survive the accident in good enough shape to egress the aircraft. This means a good seat belt and shoulder harness; it also includes ensuring they attach to structure that is sturdy enough to take the load. Secure any baggage so it can’t come forward to hit you.

The second lesson is to inhibit flames as much as possible. Use firesleeve on fuel and oil lines. If time permits during a forced landing, shut off the fuel to the engine and kill the master switch.

Remember, the “firewall” is supposed to be your protection against fires in the engine compartment, not just as a convenient wall to attach components. Part 23 requires that certified airplanes have a firewall that will withstand a 2000! F fire for 15 minutes. This includes any penetrations through the firewall—the throttle, mixture, carb heat, fuel lines, electrics, etc. must include protections to delay the flames from penetrating into the cabin. Good goal for homebuilts, too. Do it right. Don’t just plug holes with RTV.

The final lesson? In addition to delaying the flames, ensure you have the tools available to help you escape before the plane is fully engulfed. A “canopy breaker” (something heavy with a sharp point) for Plexiglas. A sharp knife to cut jammed seat belts. A fire extinguisher as well, to give you more time to egress. All accessible from the pilot’s seat. Keep in mind that injuries may restrict you to a single arm, so make sure you’ll still be able to reach what you need.

Fire in the aircraft is every pilot’s nightmare. But you can combat it through good construction practices, the right equipment and proper airmanship.

Photos and illustrations: Ron Wanttaja