Sam Kurtz’s timetable for building a Van’s Aircraft RV-7A was about the same as most people who are led to homebuilding. He figured it would take five years of work before he’d be flying his dream.

Nineteen years later, he’s still building. And the clock is ticking louder.

“I figure I’ve got five, six, seven years of flying left,” says Kurtz, now retired at 73.

He’s got at least another year of work ahead of him, he figures. The Van’s finishing kit—canopy, cowling, gear, engine mount, fiberglass—as well as a powerplant and avionics all are on the “to do” list. He’s still got plenty of building left to go and a seemingly inexhaustible amount of hope that he’ll finish and fly his dream before time runs out.

“I’m going to finish this sucker,” the Sarasota, Florida, man insists.

His introduction to Experimental aircraft building started at a good age—50—for being able to enjoy a long life of aviation pleasure.

A marriage of 32 years had ended three years earlier and he had all the time he needed.

“I had a friend of mine who said, ‘You know, you and I ought to be building an airplane.’ He started building a Mustang II. It’s still sitting in his garage.”

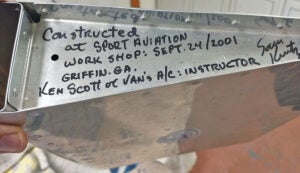

Just two weeks after 9/11, the two went to Griffin, Georgia, to take an RV building class from RV guru Ken Scott, building an airfoil he still displays proudly. He was hooked.

“I was good at it,” he says. “I enjoyed the process of figuring something out with my brain and applying it with my hands and getting good results. So right after I got home, I ordered the kit.”

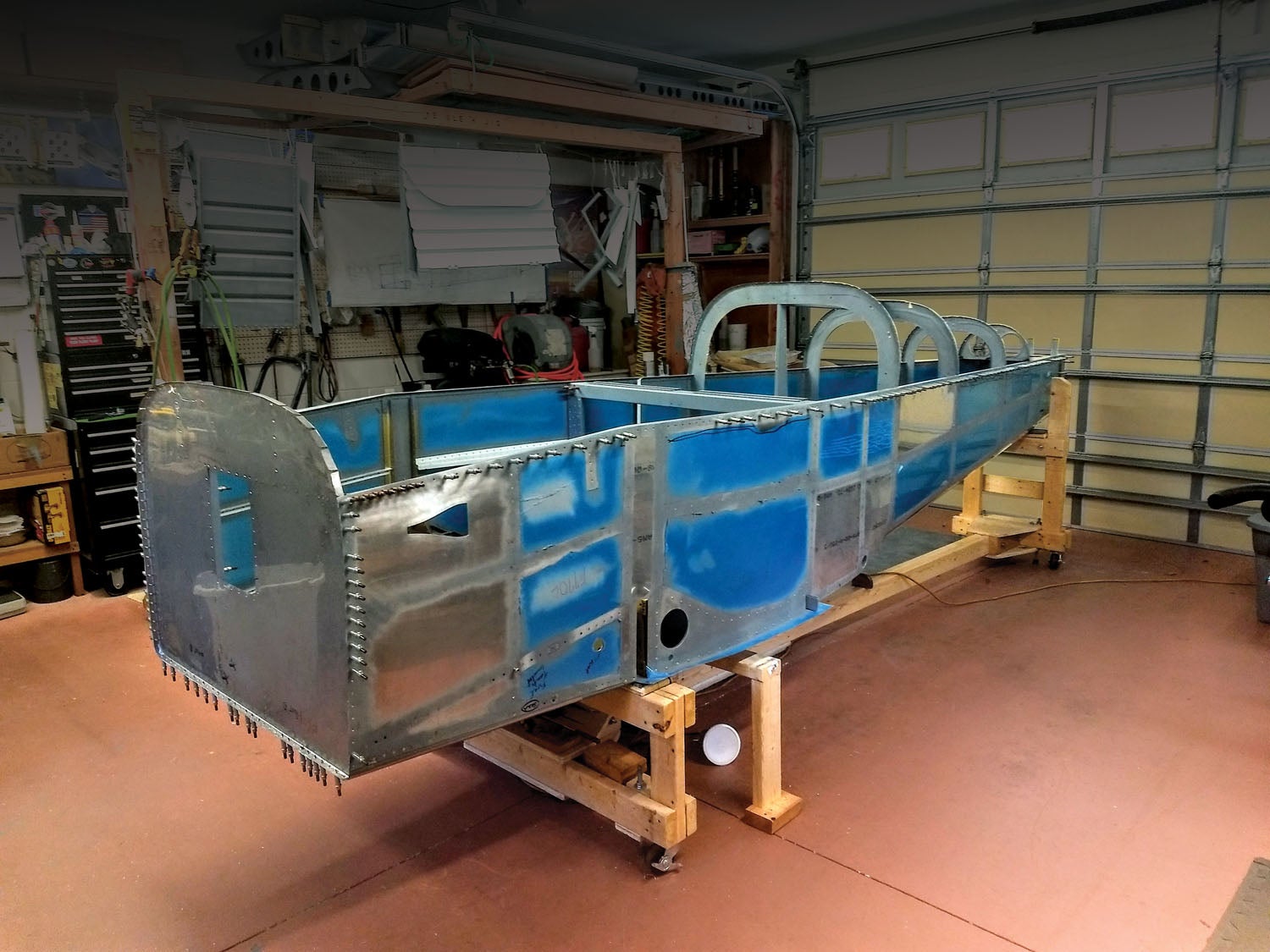

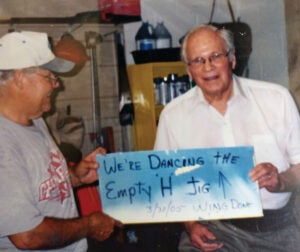

It was also great therapy to help him get over the divorce. Every day for five years, he worked on his plane. “Come home. Work. Build,” he recalls. He finished the empennage, the wings, and enough of the fuselage to reach the “overturned canoe” stage.

It was all still sitting in his workshop when he fell in love and married again. To Treva Rose, the same woman he divorced.

“We missed so much by being separated,” Kurtz laments. “When we got back together, we were totally different people.”

It was good news for the couple, of course; maybe not so much for the airplane project.

“You’re busy doing life, raising a family, making a living,” he says. “Flying isn’t the cheapest thing in the world. Cash isn’t overflowing, but it’s always been adequate. I just needed to prioritize so I forgot flying for a while.”

An electrical contractor for many years, he spent 20 years as the HVAC specialist at a local retirement center. But the upside-down fuselage in his workshop kept bugging him until he retired three years ago.

“I kept saying, ‘I’m going to finish it.’ But time kept moving on,” Kurtz recalls.

Now, it’s worth pointing out the obvious here: The best way not to restart an airplane building project is the same as the best way to keep an airplane in the sky—don’t let it stall in the first place.

For Kurtz, restarting was a matter of saying, “I’m going to finish it” every time he looked at it.

He wonders now if his project would have been better off if he’d stopped flying after initially abandoning it.

“I joined a flying club,” he says. “That took care of my flying needs but it curbed my building urge.”

He thought about joining the parade of builders selling half-finished projects, but acknowledges he’s too stubborn to give up. So he’s back to building from 10 a.m. to 5 or 6 p.m. every day except Sunday now, and he’s got more motivation when he runs low. He’s got Treva Rose reminding him he needs to go to the workshop.

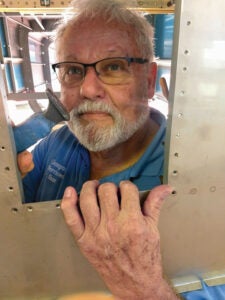

But a lot of things can change over 19 years. For Kurtz, it was the onset of arthritis.

He’s not able to hold the rivet gun and bucking bar as well anymore, so he has to be careful with the little riveting he’s got left to do. “It used to be a breeze, but not anymore,” he says.

“There are days, especially when arthritis comes around, I walk to the shop and it takes me an hour just to figure out where I want to go. But I’ve found that if I set my brain to it, I put my hands on it, and I start. Even if it’s slow, I’m moving.”

The mental part is much harder now. When he was first building, he had memorized all the RV-building nomenclature—drill and rivet sizes, for example—but all of that is gone now. He has had to relearn and reread.

“That’s a big shortcoming with a lot of people; they want to jump right in. But you have to read first. I just started at Page 1 of the big plans and started reading and figuring it out. I’m pretty patient,” he says.

Eight years and the Florida atmosphere haven’t been entirely kind to the upside-down fuselage. He spotted and had to remove corrosion on skins, even though he primed (NAPA 7220) and Alodined 1-inch-wide stretches of rivet lines where he’d removed the protective plastic coating. But aluminum pieces that were laid flat were fine, he says.

He’s noticed the culture of homebuilding has changed over the life of his project, too, even as avionics and the kits themselves have evolved in recent years. All present a challenge to the big picture.

When he started building, steam gauges were the norm. Now, many homebuilts are showstoppers, something that can make a guy feel inadequate with a basic “I just want to fly” project.

Kurtz doesn’t begrudge those builders—“I marvel at those guys creating masterpieces,” he says—he just tries to focus on what he’s learned and what he wants.

“I keep hearing Ken Scott and Van saying, ‘Keep it light and keep it simple.’ That’s my approach to building,” says Kurtz.

He thinks the younger people he’s mentoring are helping his motivation and can lend a hand with getting his project done. “My thing has been to try to find the mechanically inclined,” he says.

He’s sold his interest in the flying club, which gives him more resources for the project and stoked the urge to turn his project into an airplane.

The dream is back on. His daughter has moved to Middlebury, Vermont. The RV-7A will be the perfect machine to use to visit her regularly, he figures. He’s planned the route already, including fuel stops, and is pretty sure he can beat an airline flight there with his dream machine as soon as it’s done.

Next year.

Good article!

San we’re are you located it

Great job Sam. I have known you for a long time. It is good to the progress on your project. I want to be at the airport for the first flight.