The theme of this month’s column was conceived on March 26, 2021, which was the 40th anniversary for my wife Evelyn and me. As “Evie” and I traveled to Sedona for a getaway to celebrate our anniversary, I couldn’t help but reflect on how my vocation in aviation and avocation in Experimental aviation would not have been possible without her willing sacrifice and loving support. For as long as I can remember, I have been blessed with the curse of passion for all things aeronautical—I just didn’t always believe that realizing this dream would be possible.

We had just been married for a short while with a toddler future pilot and a new baby on the way when I, as a private pilot with barely 100 hours, approached Evie delicately about finishing my ratings and pursuing an aeronautical career. Without hesitation, she told me to do it while our family was young and we wouldn’t feel the poverty that she knew would accompany the first few rungs of that sometimes brutal career ladder.

In June of 1985, I set for myself the seemingly impossible goal of upgrading to captain at a major airline in 10 years, much to the laughter and skepticism of many. Semi-miraculously, the goal was attained with five months to spare and, yes, I fully appreciate how lucky (and blessed) I was. It takes hard work and dedication, but it also takes plenty of luck and fortunate timing.

During the painful transition from cash outflow for ratings and time building to the meager income as a flight instructor, it was Evie who not only brought home the bacon but fried it up in the pan. Every job I took in aviation was a significant cut in pay from the previous, but seen worthwhile as an investment for the future. Several peers whose advancement stalled along the way could be traced back to the fact they wouldn’t or couldn’t make the short-term sacrifices required for a brighter future. Others just had damnable bad luck. It is often said that the way to make a million dollars in aviation is to work a million hours, and it can often seem that way. Still, it was with great personal satisfaction when I reached the point that I could take over the financial responsibilities and let Evie retire to care full time for our growing family.

Enter the Experimental

Decades later, when I first breached the idea with Evie of building an airplane from a kit, I wasn’t quite sure how she would react. I was pleased that the first words out of her mouth were, “Fine, but it has to have heated seats for winter and air conditioning for summer.” I may have furrowed my brow a bit to feign tough negotiating, but in reality, it took me a nanosecond to agree to those terms.

Regardless of relationship status, a career in aviation and a project as complex, expensive and time-consuming as building an airplane both necessitate a strong and stable relationship—or the utter independence of no committed relationship at all either by design or by decree.

Please don’t interpret this as pontificating that our particular old-fashioned or traditional marriage is the only relationship that can succeed in these endeavors. It certainly isn’t. All that I am saying is that after living one for myself, and witnessing hundreds of other success stories (with a few train wrecks mixed in), that embarking on an aeronautical career or a project of the magnitude of building an aircraft can put a significant strain on an unstable relationship, especially if further strained by precarious financial security. Unfortunately, we all know that there is a lot of AIDS (aviation induced divorce syndrome) in our community. Obviously there are exceptions, but generally, good will get better and bad will get worse—caveat emptor.

Moving On

In the last issue I talked about designing and facilitating the painting of an aircraft project. One of the things that wasn’t mentioned but is a prerequisite to painting the aircraft is selecting and reserving a registration number.

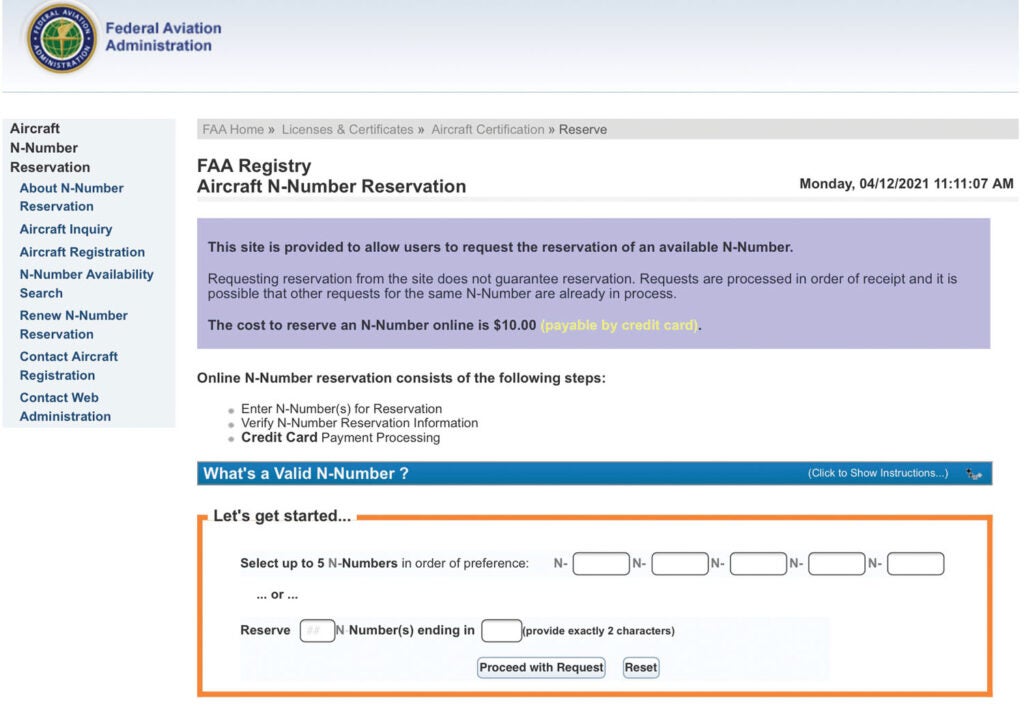

The procedure in the U.S. is to go to the FAA website’s N-number reservation portal first. There, one can search available numbers by key characters, make a reservation by selecting up to five choices in order of preference or let Uncle Sugar randomly select one for you. Previously registered aircraft, both certified and Experimental, can also change to a new number if available. Reserving a number is only guaranteed by calendar year (renewable yearly if accomplished before expiration), and securing the reservation is highly recommended the moment you decide to build. However, one thing to be aware of is that there are entities that reserve large blocks of numbers, especially those with clever character play, and then charge blue-sky commissions to release the number to individual seekers. Legal but cynically opportunistic.

Early in my build project, I found the absolute perfect number for me. I wanted the airplane number to be a small token of my appreciation to Evie for her support. (More on that later.) I dutifully renewed the saved number for the first couple of years. However, in the third year, I let the reservation expire by a few weeks. Fortunately, when I finally remembered, the number was still available, and I reserved it once again. My good fortune ran out, however, a couple of years later when I missed the deadline by only a few days and, to my dismay, my first choice was no longer available. I quickly reserved an acceptable but less desirable choice.

As I got closer to paint time, I had the idea of seeking out who might have innocently purloined my original choice to see if they might be interested in a swap of similar numbers. An internet search turned up a phone number, which turned out to be a broker who had already assigned the number. He also said, rather cryptically, that the aircraft would be in “unusual” service and the new owner, unreachable. In a last-ditch effort, I told him my sob story of the personal meaning of the number and similar number to trade. After a pause, he gave me a number to call, with the caveat that I did not mention him by name.

I called the new number, and it was even more mysterious—the individual who answered never identified himself or his company. While sympathetic to my plight and offer to swap, he said it was too late—the aircraft was already painted and already relocated to “special missions in foreign countries.” Also, kindly never call the number again. Hmmm.

Fortunately, I acquired a registration number that accomplished the primary goal of honoring my wife. Not necessarily in the sense of actual ownership, as while she enjoys traveling in the aircraft, she has no interest in flying it. The tribute is in the sense of sincere appreciation of her decades of encouragement and realization that neither my career nor the airplane build would have been possible without her unwavering support.