This month’s column is not about unmotivated or overaged adolescents living in Mom’s basement, nor honeymoon disasters. This is much more serious than those trivialities. This is about heading out to the local airport, dusting off the ship for a joyride and finding that the mission must be scrubbed due to a mechanical irregularity. In the airline world, “failure to launch” is factored into dispatch reliability, and nothing irks data crunchers more than scrubbed flights. Especially the first flights of the day, known as originators, because the delays can compound through the day and even roll into the next.

After approximately 800 hours over seven years, I have been pleased and even a bit surprised at the dispatch reliability of my Van’s RV-10. I have had two mid-trip, in-flight interruptions. One was an alternator failure on the way to OSH that earned us an unplanned visit to Hays, Kansas, to wait for Plane-Power and FedEx to get us back in the air—and catalyzed the decision to add a B&C backup alternator. The other was the sudden, catastrophic failure of an MT prop governor that turned out to be part of an isolated bad batch of units. The latter incident catalyzed my nascent media career. Nevertheless, up until a couple of weeks ago, I had escaped a failure to launch from my home airport, or any other airport for that matter.

The Present Challenge

Now to the incident in question. I went out to the city airport planning to fly up to the country airpark. I had some tasks in mind for when I got there, but the mission was simply to fly because I could make it a quintessential pleasure flight.

The airplane needed fuel, so I decided to save a few bucks taxiing over to the fuel farm instead of using truck service. The airplane fired up fine for the short taxi to the pumps. After fueling, the airplane would not start. Repeat: Would. Not. Start. There hadn’t been enough engine runtime to cause heat-soak-related issues, but I still tried every hot-start trick in the book to see if they helped. They didn’t.

Every Boy Scout knows that a campfire needs three things—fuel, air and spark. Every internal-combustion engine needs the same three things. But try as I might, nothing worked. Finally, I threw in the towel and suffered the utter indignity of begging for a tow back to the hangar. Oh the disgrace. But I guess it beats repositioning in pieces by flatbed truck as I’ve seen others experience.

Now We Troubleshoot

By the time I got the engine undressed, I was 99% sure that the problem was “spark” and not fuel or air. I had just completed the condition inspection right before a rather long trip and hadn’t had a lick of trouble since. On the plus side, I knew that the plugs were freshly cleaned and gapped. However, a nagging concern was that I also had both Bendix 1200-series mags off for 500-hour inspections. Further buzzing around in my brain was that the mag with the impulse coupler had failed the inspection because the coupler’s lash exceeded tolerances. So it was replaced even though it had never presented an operational issue. The other mag was inspected and refreshed.

One of the first rules of maintenance is to do no harm. But sometimes maintenance work causes problems that didn’t exist before. I wanted to consider that possibility, but I had roughly 10 trouble-free hours and starts, even hot starts, since the magneto work, which suggested that I probably did not have a maintenance issue related to the mag inspections and overhauls. I enjoy puzzles—but only after they’re solved.

A query of my bigger-brained buddies turned the focus away from the mags and toward the ignition switch. One suggested removing the P-lead from the coupled mag (employing all requisite “hot mag” safety precautions and procedures) and attempting a start. Voilà, the hearty 540 fired up lustily and idled like a Bernina after no more than a couple of blades. I couldn’t help but wonder if the pulled P-lead trick has ever been emergency employed in the bush over the last century or so. Merely a thought, and certainly not a recommendation.

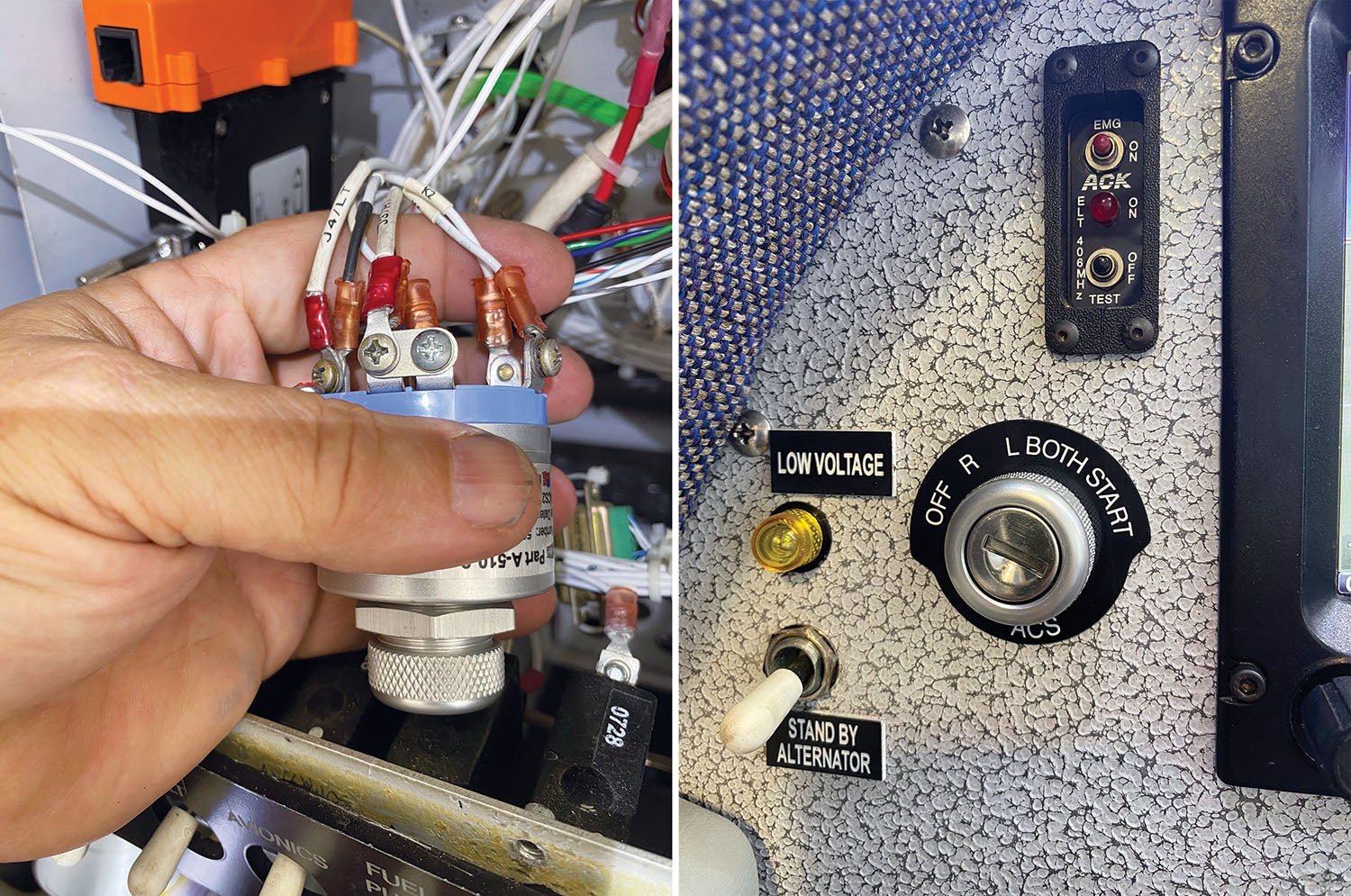

So it was off to Aircraft Spruce’s site to pursue a new ignition switch. The basic A-510-2 ignition switch has been around for decades in one form or another. It’s been subject to a service bulletin (ACS SB92-01) since 1992 for inspection, lubrication of contacts and adding a diode for the starter relay. Refurbishment/replacement options consist of an ignition switch service kit (A-3650-2), which provides replacement internal switch contacts, lubricant, diode assembly and a terminal board sufficient to comply with the service bulletin. Or replacement of the entire switch to the current spec. Since I had already significantly consumed part of my original unit’s recommended service life, I chose replacement. The cost was less than $200, which seems reasonable. Add a zero, and I would have been reaching for the rebuild kit instead. Those of us in the greater Arizona area are fortunate to have a newish Spruce warehouse in our area, and the package arrived quickly, even with the cheapest shipping option.

Making the Switch

For those of us who aren’t professionally trained mechanics, sometimes the whole electro-relationship between the magnetos and the ignition switches can be difficult to understand. Our experience generally grooms us to assume that electrical switches activate a gizmo by sending said gizmo electrical power to operate. In the case of the starter, that’s true, but it’s really kind of the opposite in the case of old school magnetos. The mags, by design, make their own power, so they are always “hot,” just needing rotation to be “actively hot.” What ignition switches accomplish with mags is they deactivate them by grounding the primary windings through the P-lead.

Replacing the switch unit isn’t difficult as long as you have easy instrument panel access and sufficient service loop in the original wiring. When building, I made an effort to employ service loops where applicable, but next time, they’ll still be a tad longer.

You should also understand when to use the supplied jumper. For the ACS switch, you need a jumper across Terminal 1 if your left mag is the “starting” mag, meaning that it has either a retard-breaker or an impulse coupling. (The terminal grounds the right mag during start so that the left mag, with the timing-retard function, is the only one firing during the start sequence.)

In an effort to pre-quell questions: Yes, at the first notification that one of my mags had failed the 500-hour service, I did consider installing electronic ignition, at least on that side. If SureFly had had a cap and harness interface for Bendix mags like they do for Slicks, I likely would have made the change then and there. Unfortunately, they don’t, and while there are additional options available to make it all happen and other attractive EI systems in the marketplace, I had a big trip coming. I didn’t want to be making major system changes just beforehand. There always needs to be a proper balance between the advantages of modern tech and the comfort of what has been field-proven for several decades.

It has been said, perhaps in a fortune cookie, that luck can be both good and bad in the same event. It depends upon perspective. This whole failure to launch thing brought that home to me. Having a component like an ignition switch die randomly at a home base fuel pump can be considered horrible luck on the one hand. However, on the other hand, the fact that the switch’s last heartbeat happened on my home field before a simple pleasure trip and not during the previous week when I was leading a large group around isolated backcountry areas was, in hindsight, fortunate. Build on. Fly on. (Fingers crossed.)

BUY A BENDIX IGN. SWITCH RV10 NEEDS THE BEST. MIKE

Had a similar situation occur at my home airport. The ACS switch failed in such a way that it sent a kill signal to both E-Mags. Instead of selecting left or right for a mag check it was sending a kill signal when you tried to start the engine. I removed that switch and replaced it with a push button start and two completely independent switches to do my mag checks. Now there is no single point of failure that can take out both my E-Mags.

My RV-10 has a Slick mag with Slickstart module on the left side, and a Surefly electronic unit on the right. One of the nice things about this arrangement is that it allows one to discard the jumper on the ACS switch that grounds one of the mags during starting. Both sides fire beginning at top dead center during cranking. Result: an IO540 that starts like a Toyota every time, hot or cold. Took ten years of flying and improving to finally shake off the hot start difficulties of the big fuel injected Lycoming.