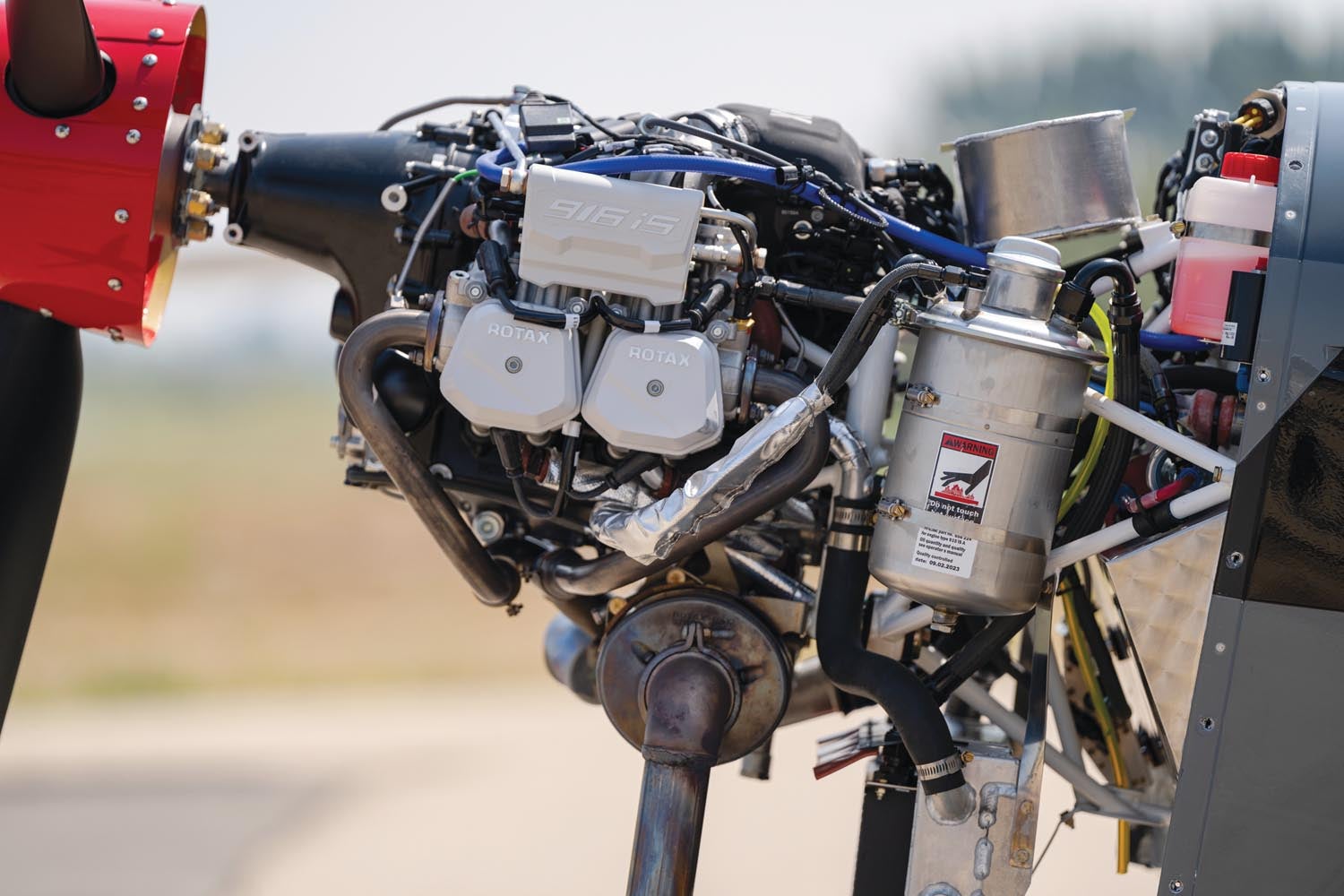

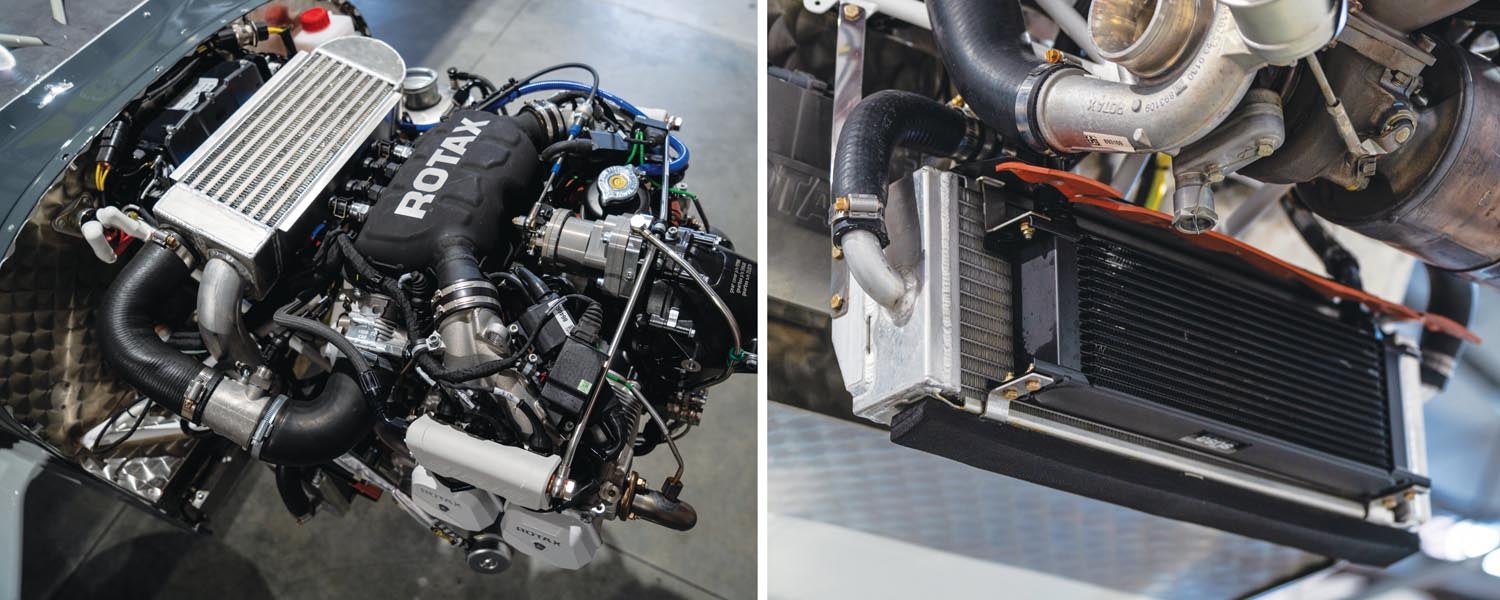

“Gee, I wish this airplane had a little less power,” said no bush pilot ever. With that in mind, 2023 is going to go down in Experimental aviation history as the year of the Rotax 916 iS, the successor to the 915 iS. The two engines are obviously family—they fit in the same mount, take the same cowlings and share a huge number of components. But the 916 is definitely stronger. While the maximum-continuous ratings are similar—135 hp for the 915 and 137 hp for the 916—the peak power ratings are far enough apart to make a difference. Where the 915 can do 141 hp for 5 minutes, the 916 punches out 160 hp for that amount of time. And that has repercussions for a large number of Rotax-powered kit airframes currently on the market.

“Gee, I wish this airplane had a little less power,” said no bush pilot ever. With that in mind, 2023 is going to go down in Experimental aviation history as the year of the Rotax 916 iS, the successor to the 915 iS. The two engines are obviously family—they fit in the same mount, take the same cowlings and share a huge number of components. But the 916 is definitely stronger. While the maximum-continuous ratings are similar—135 hp for the 915 and 137 hp for the 916—the peak power ratings are far enough apart to make a difference. Where the 915 can do 141 hp for 5 minutes, the 916 punches out 160 hp for that amount of time. And that has repercussions for a large number of Rotax-powered kit airframes currently on the market.

Let’s get a couple of aerodynamic realities out of the way. Additional horsepower (unless it is ludicrously additional) rarely gives an airplane very much more speed. Drag is what stops airplanes from going faster, and drag goes up so rapidly with speed that adding 20 hp to a 140-hp engine doesn’t add much more than 4–5 knots at the top end. Adding speed by adding horsepower gets very expensive, especially with fuel!

But horsepower buys climb and, to some extent, acceleration. Airplanes climb when they have more horsepower than they need for level flight. Let’s say your flivver needs 100 hp to stay in the air. A 140-horse motor has 40 “excess” horsepower and all of that goes into climb. The formula is rate of climb (in fpm) = excess hp x 33,000/weight (in pounds). So a 1320-pound airplane with 40 excess horsepower will climb at 1000 fpm. Going to a 160 gives you 20 more, for a total of 60 excess horsepower, so you’ll climb at 1500 fpm. That’s a huge increase in climb performance for a small increase in power.

This is why additional horsepower is important for airplanes looking for good climb performance, like those flying at altitude or trying to get in and out of tiny strips with tall trees around. Of course, the other nice thing about a turbocharged engine is that it maintains horsepower much higher, where the air is thinner. Because drag decreases with altitude, you can get a significant speed increase up high with more power. The bottom line is that a clever engineer (and we know quite a few of them) can do a lot of things with the 916 iS when it comes to climb rate or speed up high. We’re looking forward to seeing the engine applied to lots of airframes.

The Kitfox Version

This Kitfox Super Sport, built by Brandon Petersen, master fabricator for Kitfox in Homedale, Idaho, is only the second this magazine has flown but the first I have. Brandon’s beautiful aircraft, sporting the first 916 iS on a Kitfox, debuted at AirVenture and caused no small amount of buzz—so we wasted no time visiting Idaho to fly it. Logistics being what they are, we made it to Homedale about a month after seeing this airplane live in Wisconsin. Spending more time around it reveals a few things, including that it is exquisitely built. Flying it proves the new Rotax shines in providing performance for anyone headed for the mountains or simply interested in cruising high and comfortably in the smooth air.

I settled into the right seat of Brandon’s machine and immediately noticed the fit and finish—this airplane was built by a man with an eye for detail. From exceptional paint to nicely detailed upholstery and a panel fitted with a dual-screen Garmin G3X Touch EFIS coupled to a three-axis autopilot, the airplane didn’t disappoint. I hadn’t flown a Kitfox in a couple of years but was quickly reminded of the elbow room provided by the bubble doors—something that makes the cockpit roomy even for large people. The adjustable rudder pedals easily stretched out of reach for a normal-sized person like myself but just as easily adjusted back to a perfect fit with lots of travel left for the height-challenged.

Everything about the Kitfox cockpit is well thought out, with storage pockets behind the seats for headsets and small items on either side of the ample baggage area itself. The seats are comfortable, and the bar across the top-hinged door provides a comfortable spot for your outside elbow. The Kitfox is a mature design that incorporates ideas gathered from many decades of production and construction—it shows.

But let’s rewind just a moment. I have more than a few hours in the Kitfox Super Sport with the Rotax 915 iS, having taken the factory airplane into the Idaho backcountry a couple of times. But that was several years ago, so before I hopped into the 916-powered ship, Kitfox owner John McBean and I clambered into the old reliable STi with the 915 iS as a refresher on performance. The STi is a bit different aerodynamically, incorporating a STOL wing and larger tires than the Super Sport built by Brandon. But we weren’t there to sample the overall machine—I wanted to be reminded of the performance, acceleration and climb provided by the 915 engine.

The STi accelerated smartly and climbed at about 1500 fpm from Homedale, which is at 2200 feet msl. Headed south, we quickly ended up in the scab-lands of western Idaho, easily climbing over the hills and into some wonderful canyons. We surveyed a dirt strip that had been badly washed out due to recent storms and when we aborted the approach—neither McBean nor I liked what we saw, regardless of the big tires—the subsequent climb was more than enough to match the rapidly rising terrain. The STi was just what I remembered—fun, powerful and capable.

Super Sporting It

Back to the 916! When it comes to operations, the average pilot used to flying behind a 915 would have a hard time figuring that there was anything different under the cowl. Turn on Lane A, Lane B, two fuel pumps and hit the starter. The 916 iS rumbles to life with a throaty, hefty feel—a little more throaty than a 915, but not significantly. Like any of the Rotaxes, warming the engine is important, and it can take more or less time to get the oil to 120° F depending on OAT. Flying this one in August, we were ready to go by the time we’d briefed and taxied to the end of the runway. I let Brandon fly the takeoff so that I could concentrate on the acceleration—and I wasn’t disappointed!

The 916 with the MT constant-speed prop pushed us back into our seats and the airplane levitated almost before Brandon could get the throttle all the way in. Initial climb was spectacular, with Vx at about 60 mph (52 KIAS)and Vy only 5 mph faster (65 mph/56 KIAS). (Kitfox is testing to see if the 916 might do better with a Vy of 70 mph/61 KIAS.) With the two of us aboard, we were climbing out at 1800 fpm or more. Climb gradient was noticeably steeper than in the 915-powered aircraft, and that is what you need in the mountains.

Brandon related that during their initial flight testing, they found that takeoff (roll) distance wasn’t really any shorter with the 916 than with the 915. But consider that we’re talking about two different engines in different airframes, and that the STi has taller landing gear that puts the airplane at a greater AoA just sitting on the ground. Logic dictates that the 916, with more static thrust, will accelerate quicker. But there isn’t currently good apples-to-apples data to say that it would get out using less runway. Even so, the 916 airplane will climb more aggressively, making it ideal for shorter backcountry strips in the mountains.

To test cruise performance, we sampled the airplane at a few power settings at 9500 feet density altitude. Burning 7 gph (35 inches of manifold pressure and 5500 rpm), the 916 Kitfox hits 127 mph true (110 KTAS). Pull back to 30 inches/5300 rpm for 5.4 gph and 122 mph true (106 KTAS). An example of economy cruise: 24 inches/5300 rpm on 4 gph, resulting in 110 mph true (96 KTAS). Consider that the turbo Rotax would allow the Super Sport to keep gaining speed—mindful of a 140-mph Vne—with altitude and still have the climb performance to make getting to those higher altitudes worth the effort.

Other than the extra horsepower available for takeoff and climb, the “new” Kitfox exhibited the same fun flying qualities of the other available versions. It is as nimble as any light airplane, and the controls are harmonious. It will definitely teach you to fly the rudder—keeping the ball centered will wake up your feet if you’re used to airplanes that take care of that for you. It handles well on the ground (during takeoff and landing), with the typical “squishy” handling of the big-tire crowd. But it’s completely controllable. The soft tires tend to cause just a few microseconds of lag when you put in a steering effort on pavement—wait for it, don’t add too much, then the airplane will respond. Get anxious because the response is slightly delayed and put in too much and the ride will be just a little more exciting. As usual, these tires shine on grass or gravel.

The Kitfox is excellent at flying slowly—one of the reasons it is a preferred choice for backcountry STOL flying. The Super Sport wing is less of a STOL platform and more optimized for cruise—but don’t let that fool you. It will easily get in and out of any reasonable place that you want to camp. If you simply have to go somewhere shorter than, say, 600 feet, then you might want the other wing. But be honest: How often will you do that? Most backcountry strips are 1000 feet or more. The nice thing with the 916 is that if the strip is down in a hole or canyon, the big engine will get you up and out with ease. Climb is life in the mountains.

Aside from the excellent slow-speed handling (the airplane goes wherever you like with the AoA beeping quickly in your ear, signaling that you are close to the stall), the Kitfox is quite fun in steep turns. I had forgotten just how good the visibility is in the turn with a bank angle of 45°—the skylight and rear greenhouse combine with the windshield to almost emulate a bubble canopy when you lay it over on its side. With a Kitfox, you feel like you can just throw it around the sky with abandon. And with a good, calibrated AoA system that will beep in your ear, it’s almost impossible to screw up.

Waiting for afternoon light to capture air-to-air photos, we launched as a two-ship formation at about 6:30 p.m., late enough to catch the golden light that was tinted by wildland fire smoke from Canada but early enough that it was still bumpy from the summer afternoon heating. That can make good formation flying a challenge, but the Kitfox’s excellent control throughout its speed range gave me confidence even when it was hard to stay in position on the camera ship.

What I noticed most with the 916 was the instant power response. We set the prop rpm and forgot about it, letting the turbocharged Rotax do its thing and respond with lots of power when I needed it. The big MT prop provided drag when required. We chose a formation speed of about 100 mph, which gave us plenty of headroom at both ends of the spectrum for maneuvering with the camera ship.

Flying off a GlaStar camera ship, we had no trouble keeping up or rejoining when turbulence caused us to widen out or back from our desired position. The skylight provided excellent visibility when stepped down—the only consequence being a sore neck from looking almost straight up after a few minutes of holding position. The nimble Kitfox responded well in all axes, inspiring confidence that carries over into all parts of its operational envelope. This is an easy airplane to put exactly where you want it, be that in formation or on a tight runway in the mountains. Safety comes in part from pilot confidence.

Mr. Manners

The other thing to note was engine management in formation. It basically took care of itself. While the 916 iS is limited to 5 minutes at full power, that never really became an issue. With Brandon watching temperatures and pressures, I never had to compensate for the powerplant. He noted that everything was stable, and we never approached any thermal or pressure limits. The prop is manually adjusted for rpm but we basically left it alone.

We ended the formation flight by splitting off to return to the airport, and this is where the maturity of the overall package that Brandon has assembled becomes clear. His mission definition for the airplane included not only getting into the backcountry but flying cross-county to get there. To do that comfortably, you need to get up high out of the bumps. This engine gives you that capability.

So does the three-axis autopilot from Garmin. Most people install pitch and roll servos, but Brandon went the extra step to add a yaw damper, which really tightens up the airplane when engaged. Used to a little tail-wagging in most light Experimentals, I was impressed at how noticeable the yaw damper was, making the flight home smooth despite low-altitude bumps. Coupled with the capabilities of the G3X Touch, this is a cross-country machine that can fly comfortably in the smooth, cool air up high.

More power is (almost) always better, and the Rotax 916 iS adds power where you need it most for STOL-capable airplanes: takeoff and climb. It is an effective addition to the Kitfox lineup, providing plenty of horsepower when you need and want it and sipping gas efficiently when you don’t. Even at higher power, the 916 iS is efficient, but the economy cruise numbers are impressive—at typical cruise speeds, it’s consuming between 4 and 7 gph of autogas.

I look forward to flying more airplanes with this evolutionary motor, but wouldn’t mind a return engagement with the Kitfox when the smoke clears in the Idaho backcountry. All because, like other backcountry-inclined pilots, I almost never say no to more horsepower.

Photos: Jon Bliss.

Nice article on the Kitfox in “EXCESS HORSEPOWER!”.

It might have been interesting to address propeller efficiency, typically about 0.75 at 100 knots with an optimized prop.

That would make the difference in total power only 15 hp between the 140 and the 160 hp engines.

Ian Hollingsworth