Auto or manual? That has always been the question when discussing who should be flying the airplane. Man or machine—which is better adapted to fly a chosen course, follow a radio beam down to the ground, or make a good touchdown?

Pilots have either been accepting or decrying automation since someone hooked a bungee cord to a stick in order to reach down and find the map that had blown out of their lap and was hiding down in the floorboards of their wooden crate—and the debate continues to this day as advanced cockpits abound. Automation is seen as a benefit or a curse, and sometimes both at the same time.

The truth is that trying to draw a line between what is truly manual and what is automated is a futile exercise. If we broadly define automation as using machines to do something instead of using purely human intervention, then the airplane itself is an automation, for it allows a human being to fly through the air without having to madly flap their arms to get off the ground. That’s an extreme interpretation, of course—but where exactly do we draw the line?

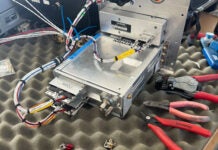

There’s no question that automation reduces workload for aircrews. Compare the engineer’s panel from the famous B-29 bomber, Enola Gay, with the full FADEC engine controls of this Cessna Citation CJ3+.

I remember enjoying going to a local park when I was a young lad because they had an old fire truck that kids could climb all over. You could sit in the driver’s seat and play with all the many and varied controls—levers, large and small, that did mysterious things. Like all good mechanically inclined boys over the age of 8 (I was probably 9), I was sure I already had a handle on how my father’s car worked. But gee—this fire truck had all sorts of stalks and things that were unidentifiable. Fortunately, my father was of an age that he knew about manual spark advance, chokes, PTO levers, and compression releases. I learned that the driver of one of those machines really had to know the intimate details of how an internal combustion engine worked in order to make it go!

Today, of course, I don’t even need to turn a key to start my car. So long as I have the fob in my pocket, I touch a button, and the computer(s) gladly feed fuel, air, spark, and other magic to the engine in the proper proportions and timing to make it instantly purr like a kitten. And it does that all without my knowing what the engine even looks like under the hood because it is covered with a big piece of plastic with not much more than a protruding dipstick to give the curious something to look at. Yes, cars have become so automated that it is hard to know what they are doing for you—and, amazingly, they pretty much keep on working…almost all of the time.

Sophisticated automation, in the guise of fly-by-wire, has been around in aerospace and large aircraft applications now for quite a few decades, but it is late in coming to the light aircraft arena. The surprising thing, however, is just how fast it is taking hold in the experimental world. No, I am not talking about fly-by-wire—although there are people working on that for some applications as I write this—but the level of automation to be found in our aircraft right now is astounding. It was not that long ago that an airplane flying a coupled approach to minimums was turbine powered and carrying passengers for hire. Now I can do that in most any of the EFIS-equipped IFR experimentals out there today. The creation of digital autopilots, coupled to GPS and equipped with navigational databases, allow aircraft to fly themselves from fix to fix and right down to the runway.

A typical cross-country for me these days requires a tug on the stick to get airborne, a few tweaks on the power levers, then a push of a few buttons to engage the autopilot to take me to my destination at an altitude I have dialed in before departure. This is followed by a descent and approach similarly programmed along the way. Deviations are handled without pulling out paper charts, just pushing more buttons. It is an efficient way to fly—far more efficient, in fact, than I can fly it by hand. The truth is, no matter how good I can do at straight-and-level flight, my mind and hands get bored. Computers don’t do that.

There are, of course, many pilots who decry all this automation. Where is the romance of flight? Where is the challenge? How can we prove that we are superior beings, capable of fine control of our machines if all we do is push buttons? Well, sure—I like to go up and challenge myself to fly a perfect loop or nail that steep turn down to a deviation of plus or minus ten feet. I love the fact that I can plant a bush plane down on a gravel bar or primitive runway and make it stop exactly where I want. Those skills are necessary if we are going to play on the edges of the flight envelope. But if we are trying to get from A to B safely and efficiently, automation is a friendly force that can help us to be better pilots.

The pilot as “systems monitor” may horrify many, and if that were all I was allowed to do in a cockpit, it would horrify me as well. But having the automation there when I want to use it is a nice option to have. It doesn’t make me less of a pilot to let the airplane fly itself while I check weather, troubleshoot a niggling problem, or get my lunch out of the bag. Keeping my head up on the big picture and letting the machinery do what machinery does is similar to me touching that start button in the car and letting the engine systems play games with mixture and timing to make things run smoothly. Yeah, there are times when it is fun to jump on an old tractor and play with all the levers to see if I can coax it to life. But that’s just to prove that I can still do it. A modern farmer is happy to let automation do the drudge work while they keep their eye on the rows. And the fireman is just as happy to let the truck take care of things, so they can manage getting water on a fire.

In the end, the important part of automation is not to reduce workload just so that we don’t have to do a menial task—it is to reduce the workload so that we can do something more important with the time it gives us. Humans are great at thinking and analyzing the unusual, the unexpected, and the unforeseen. We do an adequate job of following a guidance needle—but since the computer is generating that needle, it doesn’t take much technical effort to close the loop and let the machine fly the needle for us.

But if you really feel the need to demonstrate your ability to follow that needle, you still have the option—and I will defend your right to have that option as long as we have human seats in the aircraft. Just don’t be surprised if you see me hitting that autopilot button after takeoff, so I can start evaluating the weather up ahead without the distraction of having to stay upright.

![]()

Paul Dye, Kitplanes Editor in Chief, retired as a Lead Flight Director for NASA’s Human Space Flight program, with 40 years of aerospace experience on everything from Cubs to the space shuttle. An avid homebuilder, he began flying and working on airplanes as a teen, and has experience with a wide range of construction techniques and materials. He flies an RV-8 that he built, an RV-3 that he built with his pilot wife, as well as a Dream Tundra they completed. Currently, they are building a Xenos motorglider. A commercially licensed pilot, he has logged over 5000 hours in many different types of aircraft and is an A&P, EAA Tech Counselor, and Flight Advisor, as well as a member of the Homebuilder’s Council. He consults and collaborates in aerospace operations and flight-testing projects across the country.