“Around 2006, I was on eBay quite a bit,” said Doug Eastman of Thornton, Colorado, looking for parts for the “first airplane I ever bought, a single-seat 1953 MiG-17 that flew for the Bulgarians.” The MiG never flew before it went to a museum, but Eastman continued his eBay explorations because “it is an interesting place to look.”

Open to his next airplane project, Eastman, an Airbus A320 captain for Frontier Airlines, saw “an eBay ad for a Sorrell Hiperbipe.” It recalled memories of family trips to Oshkosh in the 1970s and ’80s, where he first saw the unique, two-seat, reverse-stagger homebuilt biplane. “I thought it might be interesting, so I went and looked at it during a layover” in Oregon.

Designed and built in Rochester, Washington, by the Sorrells (Hobie and sons John, Mark, and Tim), the 180-hp SNS-6 Hiperbipe (HI PERformance BIPlanE) made its first flight in late 1971. SNS, or Sorrell Negative Stagger, reverses the traditional placement of a biplane’s wings. As it does on the Beech Staggerwing, this improves turning visibility and makes stalls more docile because one wing loses lift before the other.

Acclaimed as the Outstanding New Design at Oshkosh 1973, instead of producing plans and parts, the Sorrells refined the design and then created kits for the SNS-7, which was the only way to get plans. Different sources somewhat agree that Sorrell Aviation sold roughly 50 of them.

The Oregon SNS-7 was in rough shape, so Eastman made an appropriate offer. “I was going to finance part of the airplane, and part of that process involved comps, finding the prices of similar airplanes, and this airplane,” he said, pointing to the luscious red Hiperbipe that he’d just spent 10 years rebuilding, AirVenture Cup racer #701, “is one of the comps.”

system out of the wing panels.

When the eBay biplane deal didn’t happen, Eastman still wanted a Hiperbipe, so he started calling the owners of the comp airplanes. “This one was still for sale. The pictures I saw were maybe 10 years old, so I went to St. Louis and looked at it.”

Like the Oregon Hiperbipe, the St. Louis example was in rough shape, said Eastman. Just to make things interesting, the woman selling the airplane (for a deceased relative) couldn’t find the logbooks, and she searched for months. She accepted Eastman’s adjusted cash offer, and he took the airplane apart and hauled it to Denver on a flatbed trailer in 2008.

“Because there were no logbooks, I knew I’d have to go through and overhaul everything—prop, engine, airframe—to create a new set of records.” Based on some work orders he got with the airplane, “the best we can tell, it had been out of annual for a couple of years, so maybe it last flew in 2005 or 2006. It was built in 1982 and logged about 900 hours on its airframe and engine.”

Touching Every Nut and Bolt

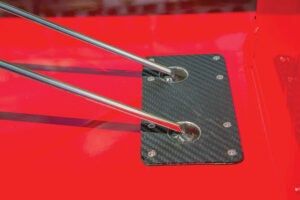

Stripping the airframe to its individual pieces, Eastman “touched every nut and bolt.” Framed with 3/4-inch square 4130 steel tubing, the constant-width fuselage has no compound curves. Essentially a center-section airfoil, the fuselage provides a 42-inch-wide cockpit for two and 80 pounds of baggage. The torque tubes that are the leading edges of the four full-span flaperons extend into the all-flying fuselage, keeping the control system out of the wing panels.

The fuselage was in great shape, said Eastman, with crack-free welds and no corrosion. And the logic of square tubing became clear. Instead of fishmouthing round tubes, band saw angles delivered a perfect fit.

The stressed plywood-skinned wings, on the other hand, were in no shape to fly. In the era of this Hiperbipe’s birth, resorcinol (aka resorcinol-formaldehyde) was the go-to adhesive. Introduced in 1943, it withstands prolonged exposure to water and ultraviolet light. But unlike the epoxy resins that superseded it, resorcinol does not eagerly fill gaps. To create strong and lasting bonds, builders must create close-fitting joints and clamp them under pressure.

In 2004, the Sorrells issued a bulletin for resorcinol-built wings, said Eastman. “Over time, there had been some issues where the I-struts connect the upper and lower wings. The twisting moments caused some cracks,” which required further inspection to determine the need for a wing rebuild.

Eastman’s airplane had cracks. “After stripping the fabric from the sheeted wings, I worked a putty knife under one corner of the plywood, pried it up, and with minimal effort, the whole sheet came off, which I was kind of expecting. Then I took a rubber mallet to all of the ribs, and with just a few taps—boop—the ribs just fell out.”

Clearly, “it was time to rebuild the wings.” Thankfully, the wood was in good shape. Eastman kept the spars (three per wing panel) and all of the ribs. “I removed the resorcinol residue and put them back together with T-88 epoxy resin.” Each wing panel consumed a month of part-time work.

From start to finish, Eastman said the Hiperbipe was a part-time project, his third, if one counts a Citabria he recovered and the repair and recover of a friend’s ground-looped Skybolt. Being a self-described “lazy airline pilot, I worked with an A&P who inspected and signed-off my work” as necessary. For questions focused on wood and fabric, he turns to “a gentleman at the airport who rebuilds Beech Staggerwings.”

Gas and Go

“If memory serves, the motor in this airplane, an IO-360-B1E, came out of a Piper Arrow, which has an aft-facing induction system,” said Eastman. A friend had a Skybolt with an O-360 that became an IO-360 with an Airflow Performance fuel injection system, port polishing, and 10:1 pistons.

“The engine was just too good to pass up, even though it has a forward-facing sump on it,” said Eastman, who bought the airplane when the octogenarian retired. “He still had magnetos on it, so I called Klaus Savier, who is part of our AirVenture Cup racing group, and bought a dual Light Speed electronic ignition system from him and put it on.”

After selling the Hiperbipe’s original engine to another homebuilder, “all told, the motor ended up costing me about $6000, about a third of what it costs to overhaul an engine, so it worked out really well,” said Eastman. “Like every good homebuilder, you’re always trying to find and figure out ways to save money. It’s all about efficiency and economy.”

During its overhaul, the Hartzell counterweighted prop got a new hub, said Eastman. The shop “called [the original] ancient. I don’t know if that was an insult or not, but it had been on the airplane since 1982.”

Originally, the Hiperbipe carried 39 gallons of fuel in the space between the firewall and instrument panel, 13 gallons in a tank with an aerobatic flop tube. Eastman replaced them with two 16-gallon tanks.

“I’ve always like smoke systems, a fun thing to have in an airplane, but I really didn’t want to put [the smoke oil tank] in the battery/baggage compartment because of the airplane’s CG,” Eastman said. With his new system, “the left tank can run smoke oil, and I have it plumbed through pump injectors in each exhaust pipe.” The plumbing also allows it to carry fuel. “When I go to an airshow, they often give you gas and smoke oil for participating. Smoke oil is about $10 a gallon and avgas is half that, so I always top off on oil.”

Eager Avionics

Like many pilots, Eastman enjoys new technology. Early in the project, he replaced the Hiperbipe’s steam gauges, mounted on a wood panel with metal side mounts, with Dynon’s EFIS-D100 and EMS-D120. Little more than a year later, and several years before the Hiperbipe flew, Dynon introduced its SkyView system, he said. “Note to self, always put technology purchases toward the end of your project…and/or don’t wait 10 years to finish the project.”

Nimble aerobatic airplanes require more hands-on work to maintain straight-and-level flight to distant destinations, so Dynon’s two-axis autopilot reduces the workload of flying the Hiperbipe cross-country, said Eastman. Accompanied by his partner and nonflying copilot and navigator, Lisa Gallegos, “our trip to Oshkosh with the AirVenture Cup race was about 6 hours, and the autopilot made for a pretty comfortable cruise,” said Eastman.

It’s not an IFR airplane, he said, but the Garmin SL30 nav/com feeds “nice to have” glideslopes to the Dynon. A Garmin GMA 240 audio panel, Garmin GTX 327 transponder, XM radio, and SkyGuard’s in-and-out TWX ADS-B system that displays traffic and weather to his iPad completes the panel.

“Wiring is not as difficult as you think. It’s a new skill set, and anyone can buy crimping and pin tools. The Dynon system is essentially a two-wire Ethernet conversation among all of the boxes, including the autopilot. Dynon’s manuals are excellent, and so is their technical support. I didn’t have to call them a lot, but when I did, they were very helpful,” said Eastman.

“Pinning things is really not as hard as it sounds. If you take your time, label, and double-check your pin-outs, everything lights up when you turn on the power, and it is a happy day. Still, as much as you stare at and triple-check everything, it’s scary the first time you power it up.”

To finish the cockpit, Eastman bought custom-made leather seats, “with seat heat, so my copilot Lisa will always be comfortable in winter,” said Eastman. “It only cost $100 more to add [heat] to leather seats, so why not?”

The black and red seats, with yellow trim, match the Hiperbipe’s paint scheme. “The airplane was originally white with a seafoam green stripe. Anything red just looks good, like it is going a hundred miles an hour.”

Eastman developed the scheme by asking friends to evaluate his different designs. He covered the airplane with Superflite. “There’s a lot of red on it,” he said. Not only is red the most expensive color, it’s heavy. Empty, the red airplane weighs 30 pounds more than the original.

Eastman really likes the look of carbon fiber, and he found an easy way to employ it on his main gear legs and instrument panel. “I’ve never really worked with it, and I don’t have the equipment for vacuum bagging it,” but 3M makes a look-alike vinyl that wrapped nicely around the cut-down Harmon Rocket fairings that streamline the spring-steel gear legs.

Calling the finished airplane “old school, new school, I retained as much of the original as I could,” said Eastman. Besides the avionics, other new-school replacements include Grove wheels and brakes, wheel pants from Van’s Aircraft, and an Odyssey battery on the firewall.

First-Flight Paperwork

Eastman didn’t closely count his 10 years of work, “but I’d guess there’s a good 4000 or 5000 hours in it,” much of it sitting in his hangar at Broomfield, Colorado’s Rocky Mountain Metropolitan Airport (BJC), contemplating “should I do this, should I do this over?”

The Hiperbipe flew in December 2017. “Lisa’s parents were in town for Christmas, so I snuck away to the airport when they went out shopping. Things can go wrong, so you don’t want a lot of distractions or lookie-lous. I’d done a number of ground runs, so I pushed the airplane out of the hangar and went flying for a half-hour. I sent them a text when I landed.”

To earn the FAA paperwork that made that flight possible, Eastman approached the project as a repair to reestablish the lost logbooks. This included inspections after stripping the airframe bare and before recovering it. Along the way, he changed the N-number to reflect the Hiperbipe’s serial number, 278, and its defining initials.

Reviewing the airplane’s operating limitations with an FSDO inspector was another step toward an airworthiness certificate. A Nebraska builder named Carlson created the Hiperbipe in 1982, Eastman said. “He flew the airplane but did not do any aerobatics, so the limitations did not include acro.”

When noted aerobatic and airshow performer “Wayne Handley bought it, he put the airplane back in Phase I and got it approved for all aerobatics in 1988. When we sat down with the FAA, the inspector asked if we should do anything with the limitations, and I said no, let’s not, so we retain the aerobatic limitations.”

Never intended for unlimited aerobatic competition, the SNS-7 is capable. “When the Sorrells say their airplane is aerobatic, they don’t mean they simply beefed it up to qualify for the legal plus 6 minus 4 Gs,” wrote Ralph Seeley in the March 1977 Sport Aviation. “They mean that airplane is designed to do aerobatics easily and well.”

An airshow acrobat in a 180-hp Pitts, Mark Sorrell demonstrated the Hiperbipe’s capabilities with outside loops, eight-point rolls, vertical four-point rolls, and tail slides. “It is a unique, fun homebuilt. I’ve had several good aerobatic flights in it, but I haven’t yet expanded my acro horizons in the airplane,” said Eastman.

The 2018 AirVenture Cup race was the airplane’s first big trip. Eastman said it was “a good way to start the airplane’s career.” He saw the race advertised just before its first flight and thought it would be fun. He wasn’t wrong.

The Hiperbipe was the sole entrant in the Unlimited Biplane category, Eastman said, “First race, first trophy.” Race #701 covered the 429.18-mile cross-country course in 2:59:26 at an average speed of 143.51 mph. “There was a fair amount of headwind, and everyone was 20 to 30 mph slower,” Eastman said.

“As the airplane sits today, it is only about 95-percent done,” he said, looking at the bright red biplane tied down in a corner of the homebuilt parking reserved for AirVenture Cup racers. “There are still things I want to change, a fancy round-inlet speed cowl and matching plenum, but I had to get it to OSH this year.”

Photos: Scott M. Spangler