Suddenly it’s cool to talk about Deltahawks.

Suddenly it’s cool to talk about Deltahawks.

It wasn’t always that way. The Racine, Wisconsin based company has been promising their all-new engine for many years and faith that anything would come from all the press releases and thinly-staffed trade show booths had worn their story to the bone.

But things are different this year. Deltahawk has arrived at AirVenture with a nice new booth, display engines, engineers on hand, two aircraft with Deltahawk V-4’s installed and most importantly, FAA certification. That last part is so easy to say but so difficult to achieve, yet despite we naysayers Deltahawk has met that difficult goal. It’s a rare achievement and gives them instant entree to the important certified airplane world.

Deltahawk has given us plenty of technical and marketing information at the show, which we’ll cover in detail later in KITPLANES, but for now here are the highlights.

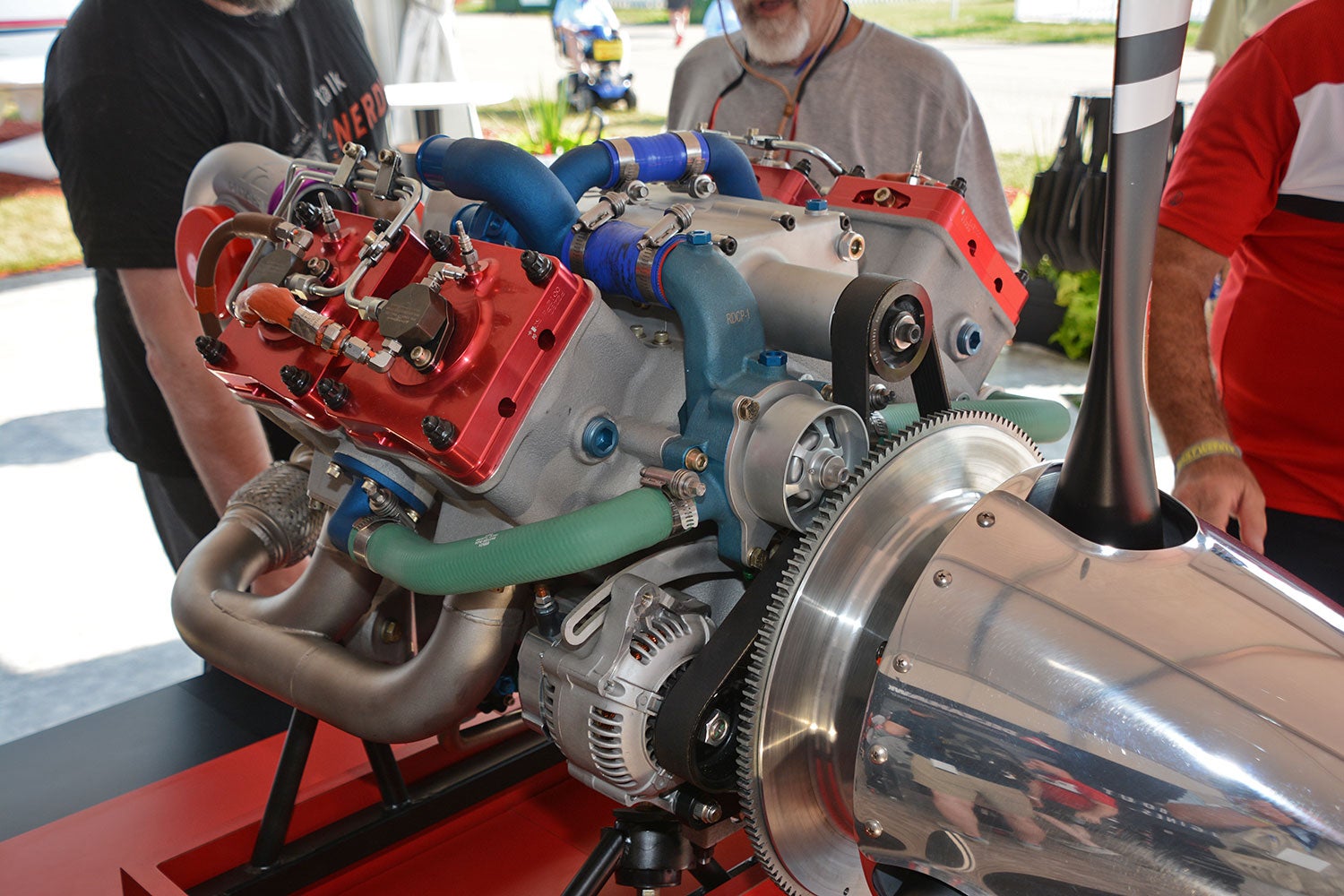

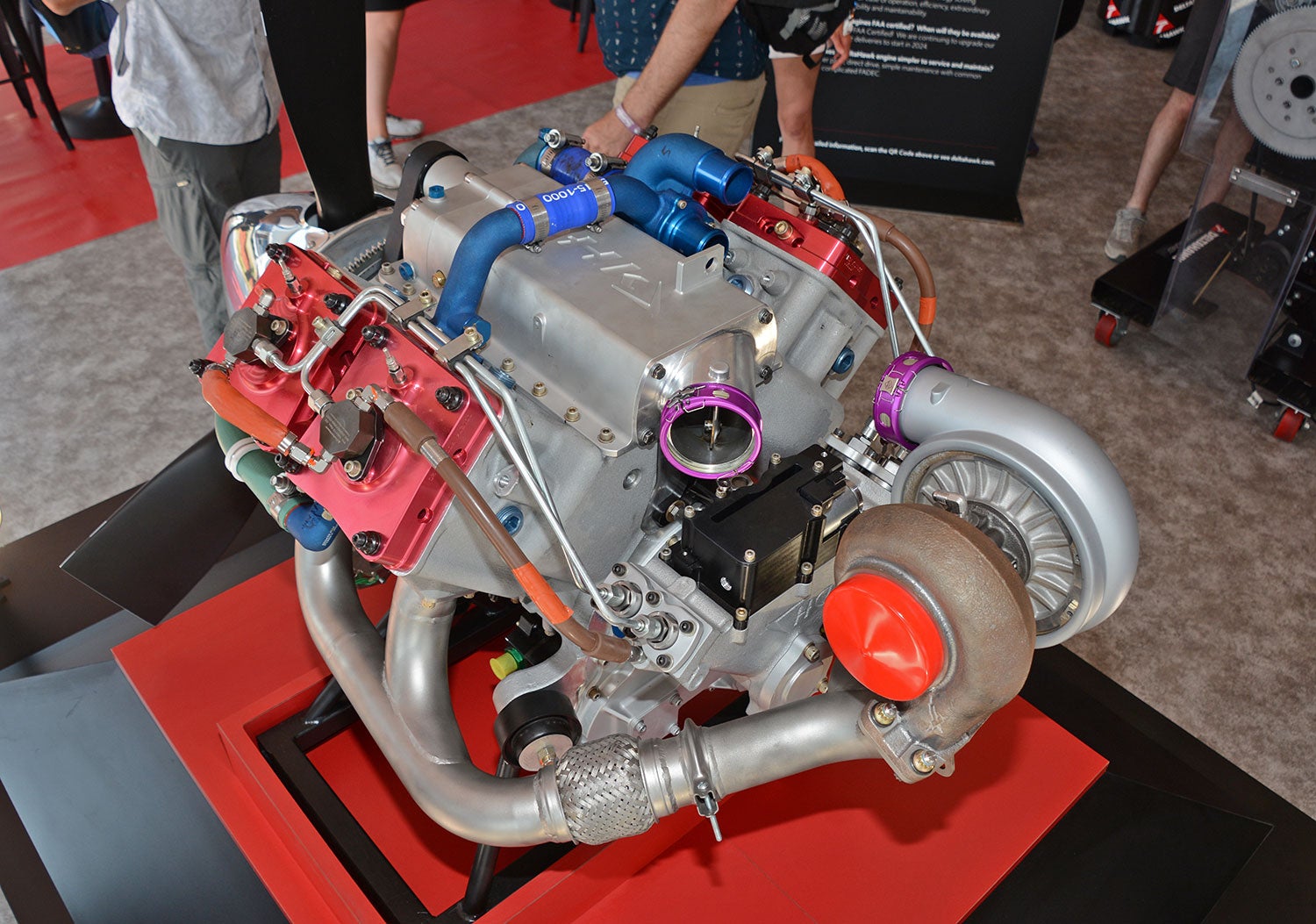

The engine is a two-stroke, Jet-A burning compression ignition, 90-degree V-4. A screw-type compressor (mechanical supercharger) and a turbocharger are fitted to provide intake boost at all engine speeds; an intercooler is mounted between the compressor and turbocharger.

The all-new engine is specifically designed for aircraft and can be mounted in any orientation as a tractor or pusher. Reverse rotation of the direct drive engine is easily possible for “handed” applications as a 2-stroke can rotate/breathe in either direction. Simplicity was the central hallmark of the design, and it is indeed elegantly spare engineering-wise.

Ease of maintenance was also a design goal, with every accessory mounted on the outside of the engine, all the way down to the dry sump oil pump. There are no electronics; fuel is supplied via old school Bosch-style fuel injection with plunger-type injection pumps and there is no ignition system, of course.

The initial offering is the DHK180, displacing 202 cubic inches (3.3 liters) and rated at 180 hp. Cylinders can be added to form a V-8 or even larger engines. But that’s getting well ahead of ourselves.

What’s going on right now is continued engine dyno and flight testing, both for detail development and durability. Deltahawk has a Cirrus and Twin Velocity with DHK180’s installed on display at AirVenture, both presumably test beds.

Deltahawk principals say production parts are being manufactured already and delivery of customer engines is slated for the first half of 2024. Deposits are being accepted and a 24 months or 2000 hours, whatever first, warranty established. That can be extended to 36 months with data download and oil analysis.

Recruiting for service providers around the world is ongoing, a training program is online and firewall forward packages are in development. Deltahawk says response from all major certified airframers has been rabid as the engine holds major promise wherever 100LL fuel is unavailable or extremely expensive, which is just about the entire world save North America or parts of Europe.

And there is the big advantage surrounding the Deltahawk: it burns widely available and affordable Jet-A. There are many other potential wins in the Deltahawk design. It is a simple, but not basic engine that promises good performance and what should be excellent fuel economy (Deltahawk says 35 percent better than comparable gas engines). The parts count is impressively low, weight should not be a major consideration, there is no valve train, so less manufacturing expense and no valves to stick or burn. Breathing should be excellent with no valves obstructing the path, just big, open ports to control the boosted air. Likewise we expect great torque from this layout and even with no propeller reduction unit it should provide superb thrust at low, quiet, propeller-friendly rpm. There’s much to like here.

There are, of course other considerations. The largest right now is the Deltahawk is not a proven entity. We should not have too much longer to wait as its mechanical and business viability will most likely be decided in the next year+ as the world gains real-world experience with the DHK180.

Our initial impression is the Deltahawk looks like it has the chops to succeed. Certainly there are going to be hiccups, but as long as the core power-producing section of the engine proves demon-free whatever development challenges arise with the peripherals should be easy to fix. There is no revolutionary technology here—in fact some of it is very time-tested—and with everything mounted to the outside of the engine changes should be rapidly and inexpensively accomplished.

Above all, the Ruud family is providing the vital capital underwriting Deltahawk and their loyalty to the program appears deep-seated.

For kit plane builders the Deltahawk holds long-term promise if not immediate viability. With big engineering bills to pay, small production runs needing ramping up, along with their 100-percent U.S. engineering, manufacturing and funding there is no way the Deltahawk can compete toe-to-toe on price with the big established engine makers. Guestimates of $100,000 retail for firewall forward packages seem plausible, which is quite a hurdle for the garage-building set even if it can be absorbed in stride by certified plane makers.

Other thoughts are the Deltahawk uses a bed-style engine mount, so engineering that into kits raised on Dynafocal ring mounts will take some adjustments. Cowling for radiators and intercoolers is also needed so we’ll keep in mind the Deltahawk is not going to be a drop-in replacement for horizontally-opposed engines.

So, once again we’re reminded the price of progress is trouble, but we like what the Deltahawk offers. The many operational and mechanical advantages from liquid-cooling, including the major gain in fuel economy, are alone worth the consideration.

May this engine company receive the support and growing business that they so greatly deserve.

I also hope this company does well, competition always improves the products of the competitors (or else they go out of business). However, I am not sure Deltahawk’s overall environmental claims will be met. The valve-less two-stroke diesel engine was first successfully produced by General Motors Detroit Diesel in the late 1930’s. Great engines at the time of introduction, but emission and efficiency issues made them non-competitive by the ’70”s. Today diesel engines rely on electronics to meet current standards.

The Junkers Jumo 205 was a two stroke diesel engine that was developed in the early thirties, before the Detroit two strokes were produced. Thousands were made, for aircraft no less.

A jimmy diesel remember them years ago. Run forever if you keep them cool and oil in them cheap to rebuild but loud as hell the 3 cylinder was bullet proof. Screaming Jimmy.