Carbon monoxide is tasteless, odorless, colorless and is present in the exhaust gas produced by any internal combustion engine. It’s also a byproduct of any form of combustion where the fuel isn’t completely consumed. Yeah, so: Big deal.

Carbon monoxide is tasteless, odorless, colorless and is present in the exhaust gas produced by any internal combustion engine. It’s also a byproduct of any form of combustion where the fuel isn’t completely consumed. Yeah, so: Big deal.

Well, it is. In fact, carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning is a contributing factor in aircraft accidents. Depending on whose numbers you use, CO is a factor in aviation crashes from two to roughly 10 times per year in the United States.

How Did It Get Here?

Usually CO enters the cabin of the typical light single-engine airplane through the heater, which depends on the heat of the exhaust system to warm air ducted into the cabin. Rather than completely decowl the engine to fully inspect the exhaust system for any defects during our preflight inspections, we typically slap one of those small, circular spot carbon monoxide detectors on the panel and crank up. Safe in the knowledge that the spot will darken or change color when exposed to CO, we fly off feeling somewhat smug that we’ll be able to detect any harmful amounts of CO while in flight. We’ll even have a few more bucks left for some avgas, because that little spot CO detector doesn’t cost much. While it’s true that any CO detector is better than none, is it enough to stay safe?

The Nature of the Unseen Beast

To fully answer that question requires a bit of understanding about how carbon monoxide impacts the human body. Typically measured in free air in parts per million (ppm), CO bonds to our bloods hemoglobin to create carboxyhemoglobin, which now can no longer perform its normal job of bonding with oxygen (O2) molecules and transporting them to our essential organs. In fact, hemoglobin just loves latching on to CO, and given a choice between CO and O2, it prefers the CO by a ratio of roughly 240:1.

Once carboxyhemoglobin has formed in the bloodstream, it takes a full 5 hours for half of it to dissipate after the source has been eliminated. The only way to flush the CO out of the body any faster is to place the victim on pure oxygen (which has its own share of hazards), typically in a tightly controlled hospital environment.

Worse still, it doesn’t take much CO to eventually begin dulling cognitive ability. Even seemingly small amounts, say 10 to 25 ppm, can build up in the bloodstream over several hours and affect us as if we had endured short-term exposure at much higher levels. Toss in other factors found in the cockpit, such as flying at high altitudes or adding the 5 ppm of CO typically found in cigarette smoke, and the total impact from small levels of CO becomes significant over time. In fact, CO is so good at replacing life-sustaining oxygen in the bloodstream that it takes only 5 to 15 seconds of breathing pure CO to render someone unconscious, quickly followed by death.

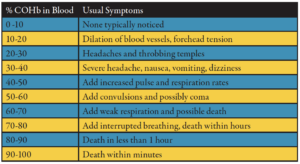

Symptoms of gradual CO poisoning aren’t always easy to detect. In many cases, the effects of sustained CO levels have been attributed to the occasional headache, nausea from motion sickness, a minor case of influenza or other vague flu-like symptoms. Of course, higher concentrations of CO will result in more severe symptoms, and Table 1 illustrates which symptoms are typically found at increasing concentrations of CO.

Even after someone has succumbed to CO poisoning, its not always simple to quickly determine that CO was the culprit. The skin of the body has a bright, rosy look to it, often misinterpreted as a healthy glow. And because CO is produced by virtually all forms of combustion, any aviation accident that includes fire while the victims are still alive makes it difficult for NTSB investigators and toxicologists to precisely determine if the concentrations of CO found in the remains are pre or post impact.

Given that our normal good decision-making capability is one of the first things to erode with increasing levels of CO, we cant depend on instantly recognizing the problem ourselves when it rears its ugly, invisible head. The good news is that CO poisoning isn’t a problem confined solely to aviation, and more and more solutions to early detection have come online in the last few years. Better still, as competition among manufacturers has increased, these units have become more affordable as well.

No Shortage of Fixes

Carbon monoxide isn’t the only gas thats hazardous to human health. Ammonia, chlorine, hydrogen cyanide, hydrogen sulfide, phosphine and sulfur dioxide could all cause harm in various concentrations. These compounds are somewhat common in industrial applications, so workplace safety dictates that methods exist for their detection. Industrial grade gas detection devices have become increasingly common as employers strive to provide the safest work environments possible.

Additionally, household CO detectors have become more available in the last few years, joining the time-tested smoke alarm as standard issue in most residences. However, a gas detector designed for industrial or household use may not be entirely appropriate for an aircraft cabin or cockpit.

When the first household CO detectors appeared on the market, they were snapped up and installed by safety-conscious homeowners. Many of them featured automatic phone line notification of the authorities should residents be overcome and unable to contact the local fire department. As good as this sounds, those first home units were easily triggered by low levels of CO, scrambling fire trucks and crews needlessly. At the time, these early CO detectors cried wolf roughly nine times out of 10.

The solution was a federally mandated desensitization of household CO detectors. No matter where the unit started measuring CO content, it was not allowed to alarm until 35 ppm, where continued exposure in the home could be harmful over time. A second, more urgent alarm would trigger at 100 ppm, where short-term exposures begin to have negative effects. This is where the triggers remain today in the U.S., except in California, where a lower 25-ppm threshold has been mandated. So before you depend on that bargain household CO detector to keep you safe from harm while airborne, understand that the default trigger levels may be too high to alert you to the gradual degradation of cognitive abilities, which can occur at much lower CO concentrations.

Most industrial CO detectors are better suited for aviation use than the household variety, but they still may have not all of the desired features that would make them good additions to your flight bag. For example, some may be susceptible to detection and alarm errors when in proximity to radio frequency interference (RFI), like whenever you key the mic. Some may require frequent, periodic recalibration to maintain accuracy. Some may be a single-use type unit, destined to be tossed when the batteries are dead or upon reaching a specified life limit.

However, some may be pretty close to ideal. Among the more desirable

features are easy calibration, user-settable alarm trigger levels, user-replaceable sensors and batteries, RFI shielding, rugged construction, easy-to-read displays and hard-to-miss audio alarms. Let’s compare suitable models.

The Price is Right?

Some of the industrial CO detectors have successfully crossed over into the aviation marketplace, as well as into single-household units that are designed as a low-level device, displaying CO levels well under 25 ppm. If you go online or peruse a catalog from Aeromedix, Aircraft Spruce, Sportys or the other aviation product suppliers, you’ll find an interesting mix of CO detectors.

However, I found a much wider product selection, and, in some cases, competitive pricing by browsing the online catalogs from firms that distribute industrial safety equipment. For example, R.J. Safety Supply Company (www.rjsafety.com), in San Diego, offers the deluxe Honeywell Minimax detector for less than the Sportys list price for the basic model. However, Sportys sells the rugged Quest SafeTest 90 for more than $100 less than the MSRP.

Find the CO detector that most suits your individual needs, and then research the catalogs of both aviation and industrial suppliers to find the best combination of price and availability. Some resellers contacted for this article had excellent pricing, but they were backlogged up to four weeks before the desired unit could be shipped. Prices varied significantly from reseller to reseller, and the savings realized might even be enough for a few gallons of 100LL.

Dedication to Aviation

Why hasn’t someone developed CO detectors specifically for the aviation market? Well, someone has: Ash Vij, president and founder of CO Guardian (www.coguardian.com) in Tucson, Arizona. If you’ve meandered through the product hangars at either Oshkosh or Lakeland in the last few years, you’ve probably seen Vij at his booth with a wide variety of his CO detectors on display.

From portable units intended to simply plug in to an aircrafts cigarette lighter, to certified, panel-mounted units designed to replace the 2.25-inch hole formally occupied by an aircraft clock, the CO Guardian units range in price from $150 to $700. And unlike the gas detectors designed for industrial or residential use, the offerings from CO Guardian feature some niceties that just aren’t available elsewhere.

For example, you can choose between a standalone, panel-mounted unit with a built-in sensor and alarm, or a remotely mounted unit with a RS-232 serial data output that will trigger a visual CO warning on many of the latest flat-screen multi-function displays. Or an aural warning can be summoned from the more sophisticated audio panels that come with canned warning messages. Or both, if desired, and your aircraft is so equipped.

If you don’t have one of those spendy MFDs gracing your instrument panel, you can order a simple, panel-mounted annunciator light that will shine nice and bright should CO levels become a factor and need your attention. Another added feature is the calculation of cabin altitude along with CO content, so you can factor in the effects of hypoxia to your decision-making.

One thing thats obvious is that Vij and company have thought long and hard about providing the features that are tailor-made for those of us looking for airborne CO detection solutions. Several certified aircraft manufacturers think so too, and have included some of the CO Guardian products as standard equipment in their new airframes.

Location Is Everything

I happen to fly an airplane that under the right circumstances, during climbout at a high angle of attack, will allow about 12 ppm of CO into the cockpit at the left panel vent. The source of this CO is the joint between the header pipes and the rest of the muffler assembly, which is designed to slip a bit under operation. Upon leveling off, however, the NACA vent inlet is no longer directly downstream of the cowl latches, and no CO comes in. However, a sensitive, set-and-forget-style CO detector mounted in the center of the cockpit shows no CO at all under any flight attitudes.

This is one of the advantages of having a portable detector that can be moved around the airframe. Another, of course, is being able to take it from airplane to airplane, especially when using it as a diagnostic tool during those first homebuilt taxi tests and initial flights. The source of CO contamination in some certified airframes has actually been traced back to the tailcone, where the backdraft allows CO to enter the cabin from behind. Its worth a bit of thought, and some trial and error, when measuring for CO with a portable unit or mounting that remote CO sensor in a permanent installation.

Summation

Is it worth the time, money and effort to add some form of precise CO detection to your aircraft? Given the somewhat sparse statistics on the matter, some would argue no, the risk is remote. I would disagree.

Given the insidious nature of CO and its ability to negatively impact everyone aboard before the source of the problem can be identified, accurately detecting potentially harmful CO levels is well worth the few hundred dollars. Heck, the increased peace of mind alone is probably worth that.

As some wise aviator once pointed out, “Takeoffs are optional, but landings are mandatory.” Too many flights have started off just fine, only to have the crew succumb to in-flight incapacitation after a few hours, often with fatal results. We owe it to ourselves, and our passengers, to arrive at our destination with our faculties as sharp as they can possibly be.