It could be you’ve heard the Brennand name associated with the idyllic floatplane base southeast of Oshkosh, on Lake Winnebago. Beginning in the 1970s, Bill donated the use of his waterfront land for floatplane operations and chaired the base for 20 years. Maybe you are acquainted with the Brennand

Airport, equally idyllic, a short hop north of Oshkosh. Both locales are linked to the Brennand name, though neither define the man. Nor does the fact he dated Betty Skeleton.

To my recollection, I first saw Bill Brennand in the 1990s, at a grassroots aviation gathering that happened spontaneously every Saturday morning, west of Oshkosh, on the farm of Munsil and Shirley Williams. The weekly gathering attracted all manner of aviators and aviation enthusiasts, their spouses and their children. It was everything aviation should be: accessible, friendly, diverse and fueled by coffee and donuts and, occasionally, accordion music. Stories were told. Lies repeated. Air medals re-earned. Munsil’s, as it was known, went on with or without its namesake. It was at Munsil’s that I first approached Bill Brennand. The conversation was likely brief. I didn’t know what to say to him and he was a quiet man. The ice, however, was broken by coffee. Over time our conversations expanded to include the donuts and the weather. On a lucky day, Bill would accidentally share one of his flying stories.

A Pivotal Pairing

In 1943, with a service deferment to work the family farm, 19-year-old Brennand began taking flying lessons at Wittman Flying Services. Steve Wittman—you’ve certainly heard his name—was, at that time, training pilots for the military. Prior to the war, Wittman had established a successful air racing career with two aircraft that sprang from his own mind and hands (Wittman was homebuilding in Oshkosh before EAA founder Paul Poberezny was 3 years old). His first racer, Chief Oshkosh, was raced from 1931 until 1938, when it was heavily damaged near Oakland, California. It was trailered home to Oshkosh and placed in the rafters of Wittman’s hangar while he concentrated on campaigning his other racer, Bonzo, a Thompson Trophy contender that was faster than the military aircraft of the day. Wittman had also designed a two-place aircraft, Buttercup, the predecessor to his Tailwind, which he licensed to Fairchild Aircraft. The onset of WW-II, however, brought both civilian aircraft production and air racing to a full ground stop.

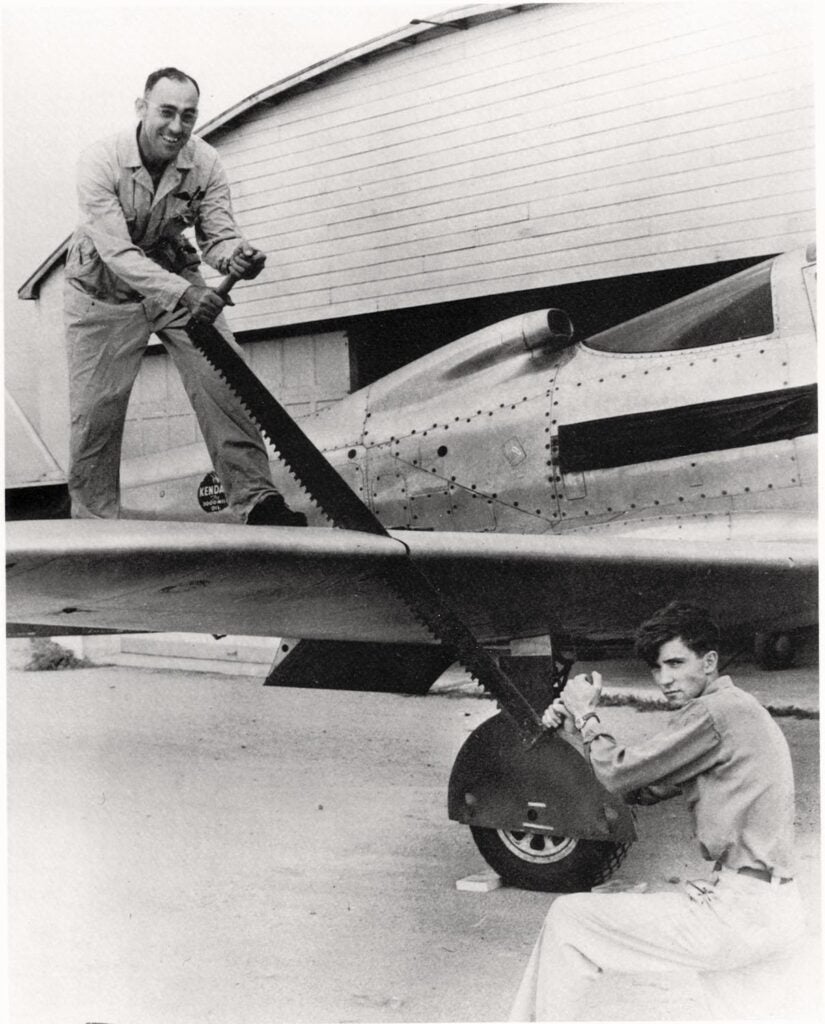

By April 1944, Brennand had earned his pilot certificate and was working part time for Wittman. Brennand said the first thing he worked on with Wittman was a four-place airplane Wittman designed and designated Big-X. Fairchild, like every other aircraft manufacturer pivoting to a post-war economy, envisioned returning military pilots wanting their own aircraft. But, as with Buttercup, Fairchild never put Big-X in production. For Bill, however, building an airplane with Wittman was “amazing in every way.”

All the while the injured Chief perched in the rafters. Wittman reminisced about it. Brennand dreamed about it. They both talked about fixing and flying it. In the summer of 1945, with Wittman uttering, “Yeah, I suppose that’s something for me to get killed in,” Chief Oshkosh was lowered from the rafters. Brennand knew that statement—a statement he never forgot—was meant for him. By the summer of 1946, Chief Oshkosh was reborn as Buster.

In September 1947 Bill Brennand, age 23, lowered his 100-pound frame into Buster’s cramped cockpit to compete in the Goodyear-sponsored Midget class race at the National Air Races in Cleveland. Lockheed test pilot Tony LeVier idled nearby. LeVier was experienced at both racing and winning. His airplane, Cosmic Wind, had the full, though unofficial, backing of Lockheed Aircraft and its vast resources. Brennand, a farm-boy-turned-flight instructor, had never raced. Ever. Brennand’s steed was a homebuilt aircraft built during the Depression (when it is said Wittman lived on $1 per day, including what he spent on building his airplanes). It was raced, wrecked and raftered before being resurrected in its new configuration. Bill had only flown Buster 10 hours for recreation before being sent to compete in Cleveland.

September Surprises

A rescue crew arrived as Brennand swung Buster’s canopy open. Buster’s propeller broke during Bill’s final qualifying flight, forcing him to pull up and glide over the grandstand for an emergency landing. “What happened?” the rescue crew asked. “I don’t know,” Bill replied, “I just got here myself.” The next day, with a borrowed propeller, Brennand won the inaugural closed-course Goodyear Trophy race with an average speed of 165.8 mph. Tony LeVier finished fourth, at 159.1 mph.

Some 60 years later, in September 2007, Bill Brennand, age 83, his storied air racing, barnstorming and aviation career behind him, lowered himself into the right seat of Metal Illness. I swung the canopy shut.

When offered control of an airplane many passengers, even pilots, demur. Those who accept often hold the controls neutral, altering neither altitude nor heading and certainly not piloting. Bill was an exception. He flew with skill and confidence. He didn’t move the controls tentatively. He wholly and instinctively piloted the aircraft without overcontrolling it. If Bill was happy to be piloting again, I didn’t see it. His eyes were outside the cockpit, where all good pilots’ eyes should be. Where an air racer’s eyes must be. My eyes were on Bill. Not out of concern, but out of awe. If Bill had performed an aileron roll or pulled up into a stall before spinning earthward I was all in. If I had any concerns they were in my ability to get Bill back on the ground with both him and my pride intact.

“I was not one to ride around the patch very much; the flight had to have a purpose. I guess 65 years of flying was enough.” Those words are recorded on the final page of Brennand’s biography. (Bill Brennand: Air Racing and Other Aerial Adventures by Bill Brennand and Jim Cunningham, ISBN: 0971163766, published by Airship International Press.) He may have spoken those words often, after health issues grounded him. While I helped Bill off my wing he said, quietly, as was his way, “I really don’t miss it. I did it for so many years.”

I was at once taken aback and relieved. I had often thought about what it would be like to have my wings clipped, to age out of ability if not desire. A few weeks later, Bill’s girlfriend gripped my forearm, held my eyes hostage with hers and delivered unexpected news. “Bill has not stopped talking about the airplane ride you gave him!” Turns out, Bill Brennand lied to me—and likely himself.

Is anyone ever going to write a biography of Steve Wittman? I have Cunningham’s biography of Bill Brennand, and enjoyed it greatly. It’s a keeper with my aviation book collection. But I understand that another writer was planning to write a biography of Wittman, but it never happened for some reason. I’ll buy it whenever it’s written!

PS: My wife and I lived in OSH from 1978 to 1988. We bought our homebuilt, a Pazmany PL-2, II 1979. It had brakes only on the left side. I bought a set of Cessna 150 rudder pedals, complete with brake master cylinders, from Bill Brennand back in the day, in the early 80s, and installed them in the Paz so I could fly from the right seat and my wife could fly from the left. We still have the airplane, complete with its C-150 rudder and brake pedal assembly.

Hi Jack,

There was a book about Wittman in the works and Jim Cunningham was trying to get the existing research from the person who was writing it, so it could be finished, but my understanding is that proved…..complicated. I know Jim would love to write that book.

Was your Pazmany parked on the Basler ramp on 20th street? I recall one sitting there about the time I was in high school and haunting the airport.

Thanks for reading!

Kerry

But where was the lie! The lie being that the tools sent couldn’t do the job, or the fact they were sent at all! I remember buying a car back in the early 2000’s that was supplied with a Tire Wrench to remove and/or replace the tire with! I wasn’t told that the Tire Wrench wasn’t even capable of actually removing a tire at all! The fact that state law required a Tire Wrench also be present at all times to pass a state safety requirements, not that the Tire Wrench itself actually had to be functional and do the job it was required to do…

Hi,

The lie was that Bill didn’t miss flying.

Kerry, that flight had to rank pretty high in the memorable special flight category! Great article, thanks for sharing Bill with us.

Jim Wheaton

Hi Jim,

Thank you for reading and commenting. Flying with Bill was certainly a highlight, but flying with my kids beat all others hands down.