Building and maintaining an airplane is a series of monumental steps separated by a long train of mundanities. Make great strides only to be held back or derailed by some seemingly picayune detail that requires more than its fair share of your time and consideration. Stuff happens.

Building and maintaining an airplane is a series of monumental steps separated by a long train of mundanities. Make great strides only to be held back or derailed by some seemingly picayune detail that requires more than its fair share of your time and consideration. Stuff happens.

And so it is with my Glastar Sportsman. Since early 2006, when I began using it for more than local test flights and general goofing-off near home, I have been ever so slightly annoyed by its com-radio performance. While it’s hard to fault the features of the Garmin SL30 that is my primary com radio—an Icom handheld is the backup—I’ve long felt that the overall performance was suffering at the hands, er, make that ears of the antenna. Symptoms: Often, flying in the desert Southwest, I would lose communication with air-traffic control when other airplanes at my altitude wouldn’t; twice I had what sounded like serious p-static encounters-loud “white noise” static overcoming the receiver; and my TruTrak autopilot would invariably do a mild pitch-up when I transmitted in the lower third of the com band. For the most part, the system worked, but I recently grew weary of having to open the SL30s squelch to keep in touch with ATC.

Like many who own composite (or, in the case of the Sportsman, partly composite) aircraft, I followed the herd and used an internal copper-foil dipole antenna bonded to the inside of the vertical stabilizer. In truth, I had good luck with such a setup in my Pulsar, but it was totally composite; the Glastar has an aluminum rudder and horizontal tail group very near this internal antenna. Attempting to fix the autopilot-interference problem, I relocated the coax runs in the cabin. They originally came down the ships centerline behind the panel, right under the autopilot-servo plate, and then back to the tail. Several hours of work to move the cables away did nothing to help the RF interference issue. Hmmm.

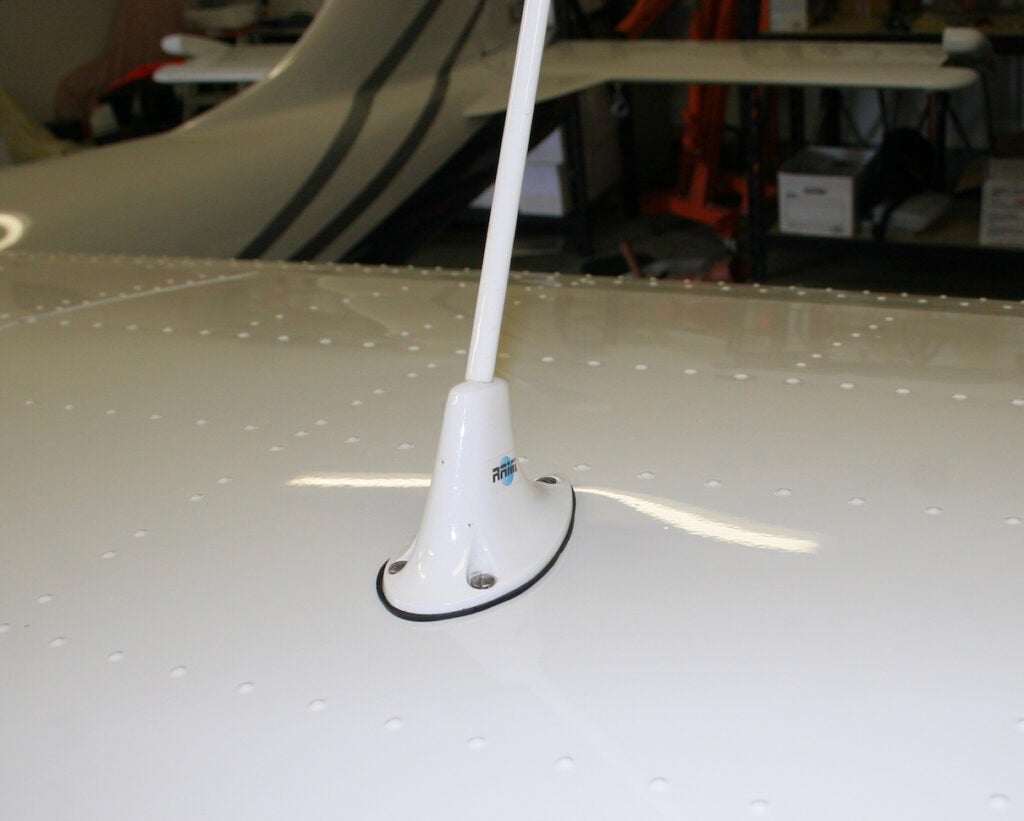

Finally, I found myself drilling through the top of my wing and installing an R. A. Miller com antenna. In fact, as a big fan of symmetry, I mounted two, as far inboard as I could get them without running afoul of the fuel tanks or flap-actuation hardware. The bases ended up one bay inboard from where the top of the strut enters the wing, making it a natural to run the coax down the strut.

In the interests of science, I flew with the right seat removed and all the old coax accessible while in flight. I wanted to see if there was any measurable difference. Turns out, there was.

The SL30 has a cool signal strength display you can watch in flight. I tuned to an automated terminal (ATIS) transmission some 40 n.m. away. Heading straight at the station, the tail antenna posted 43 on the display; the center antenna about the same. The new wing-top antenna gave a 65. Facing directly away from the station, the tail antenna dipped to 40 and the signal was noticeably weak. The stick antenna on the wing was dramatically better. Same deal after testing transmit strength with a Flight Service Station—the external antenna provided the best transmit signal. So far so good. For the final test, I engaged the autopilot and tried transmitting briefly on a number of low frequencies in the com band. No pitching artifacts. Nothing. Brilliant!

Bear in mind, this is one data point. Its possible the antennas were improperly installed-the copper tape in the tail was done before I began the project-or there was something wrong with the feedlines that I managed to work around with the new installation. Hard to say, except that I wont be going back to the old way any time soon.