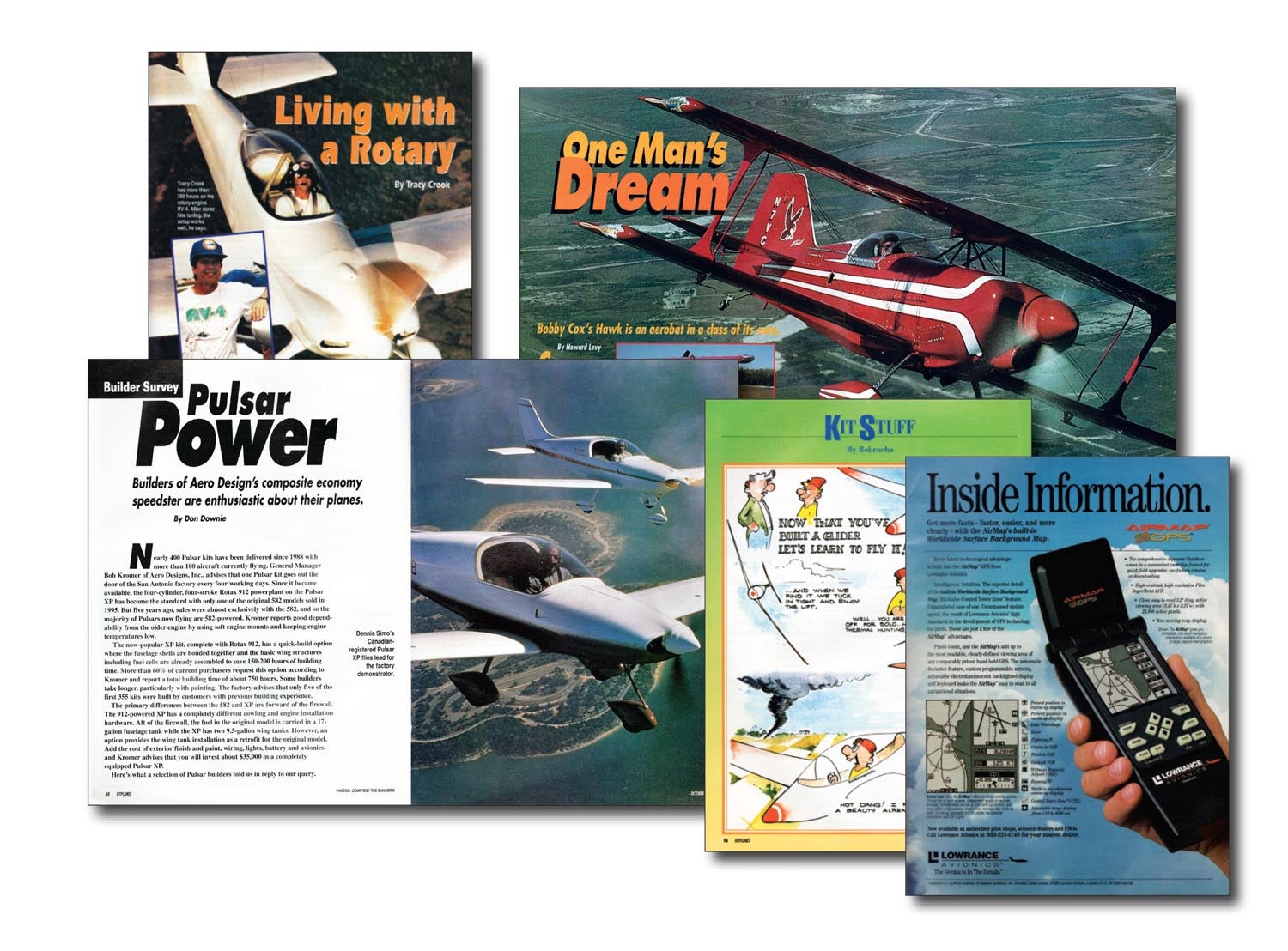

Our cover subject for the October 1996 issue was Bobby Cox’s highly modified Pitts S-1 plansbuilt that had won Grand Champion Plansbuilt at Sun ’n Fun the year before. Howard Levy interviewed Cox, a retired custom-cabinet builder and serial aviationist with a penchant for aerobatic biplanes. He flew a Pitts S-1C until “he tangled with a tree while doing low-altitude aerobatics. He was quite banged up, but not as extensively as the airplane, which caught fire after he exited it.” His custom Cox Hawk, as he called it, “more or less retained the general lines of the Pitts S-1, but that is as far as it goes.” The list of mods is extensive: swept bottom wing (to match the top), stronger wing spars, larger ailerons, a steel-tube cage that’s a “concoction of Cox and Dan Rihn (One Design) ideas” and, up front, a Lycoming AEIO-540 making 350 hp. Need we also say that pulling a 1650-pound airplane around makes easy work for the big six-banger? Cox took 30 months to build his Hawk.

Our cover subject for the October 1996 issue was Bobby Cox’s highly modified Pitts S-1 plansbuilt that had won Grand Champion Plansbuilt at Sun ’n Fun the year before. Howard Levy interviewed Cox, a retired custom-cabinet builder and serial aviationist with a penchant for aerobatic biplanes. He flew a Pitts S-1C until “he tangled with a tree while doing low-altitude aerobatics. He was quite banged up, but not as extensively as the airplane, which caught fire after he exited it.” His custom Cox Hawk, as he called it, “more or less retained the general lines of the Pitts S-1, but that is as far as it goes.” The list of mods is extensive: swept bottom wing (to match the top), stronger wing spars, larger ailerons, a steel-tube cage that’s a “concoction of Cox and Dan Rihn (One Design) ideas” and, up front, a Lycoming AEIO-540 making 350 hp. Need we also say that pulling a 1650-pound airplane around makes easy work for the big six-banger? Cox took 30 months to build his Hawk.

Tracy Crook, who helped put the Mazda rotary conversion on the map and in the minds of builders, shared a synopsis of the first 250 hours flying his 13B-powered RV-4. He described in intimate detail the challenges of keeping the rotary cool, working out carburetion and ignition bugs and staying on high alert every flight hour. After the initial shakedown, Crook reported that he had a lull period where everything worked well, eventually finding a crack in an exhaust component at 62 hours. Later escapades with carburetion issues led to a temporary engine stoppage that he was able to remedy before having to find an emergency landing site. He summed up his experience: “You need to be honest about your goals as a pilot. We are still at the point where it is up to you to design and refine many of the systems you will need with any alternative engine. To do this successfully, you almost have to enjoy the process. If the mechanical stuff is just a means to an end and you are solely focused on getting into the air and flying, an alternative engine is probably not for you.”

Don Downie authored a builder survey of the Pulsar model, noting that as of 1996 there were almost 400 of the kits in circulation and more than 100 aircraft flying. Aero Designs, the company making the Pulsar kit, had transitioned from two-stroke powerplants to the Rotax 912 in the XP model by 1992; in 1995, only one Rotax 582-based kit had been sold. Many of the builders still active in the Pulsar world were quoted in the story, Mark Burrow and Greg Smith among them. Downie summed up the results, which were strongly positive about the airplane and the build process: “So if a moderately priced composite two-seater is on your want list, consider Mark Brown’s well-proven Pulsar XP. His builders seem to like the project even if each sputters a bit about filling a maze of pinholes in preparation to paint. After all, when you’re that close to first flight, the ready-to-paint phase is one of the last projects.”

Reinforcing how far we’ve come in electronics since 1995, see the ad for the Lowrance AirMap GPS. As big as an early cell phone, the AirMap featured a flip-up antenna, a simple grayscale LCD with about the surface area of a credit card and built-in “worldwide surface background map.” At $799, the AirMap competed with Garmin’s smaller GPS 90 and 92, Bendix/King’s KLX 100 and Magellan’s EC-10X; it would morph into the smaller AirMap 100 as part of a flood of quickly updated models through the late 1990s. Little did we know that Garmin was just three years from dropping the GNS 430 on us, a unit combining com, nav and GPS functions with a color moving-map display. Mind-blowing technology at the time.