As I settle into my new life in Oregon, where I know hardly anyone but hope to know more, I find myself in the company of another airpark dweller, one who happens to be in his 90th year. It might rain, typical of the Pacific Northwest, so it’s a good time for stories. He shares his life’s tales while I cozy up in my puffy jacket and take a much-needed break from social media.

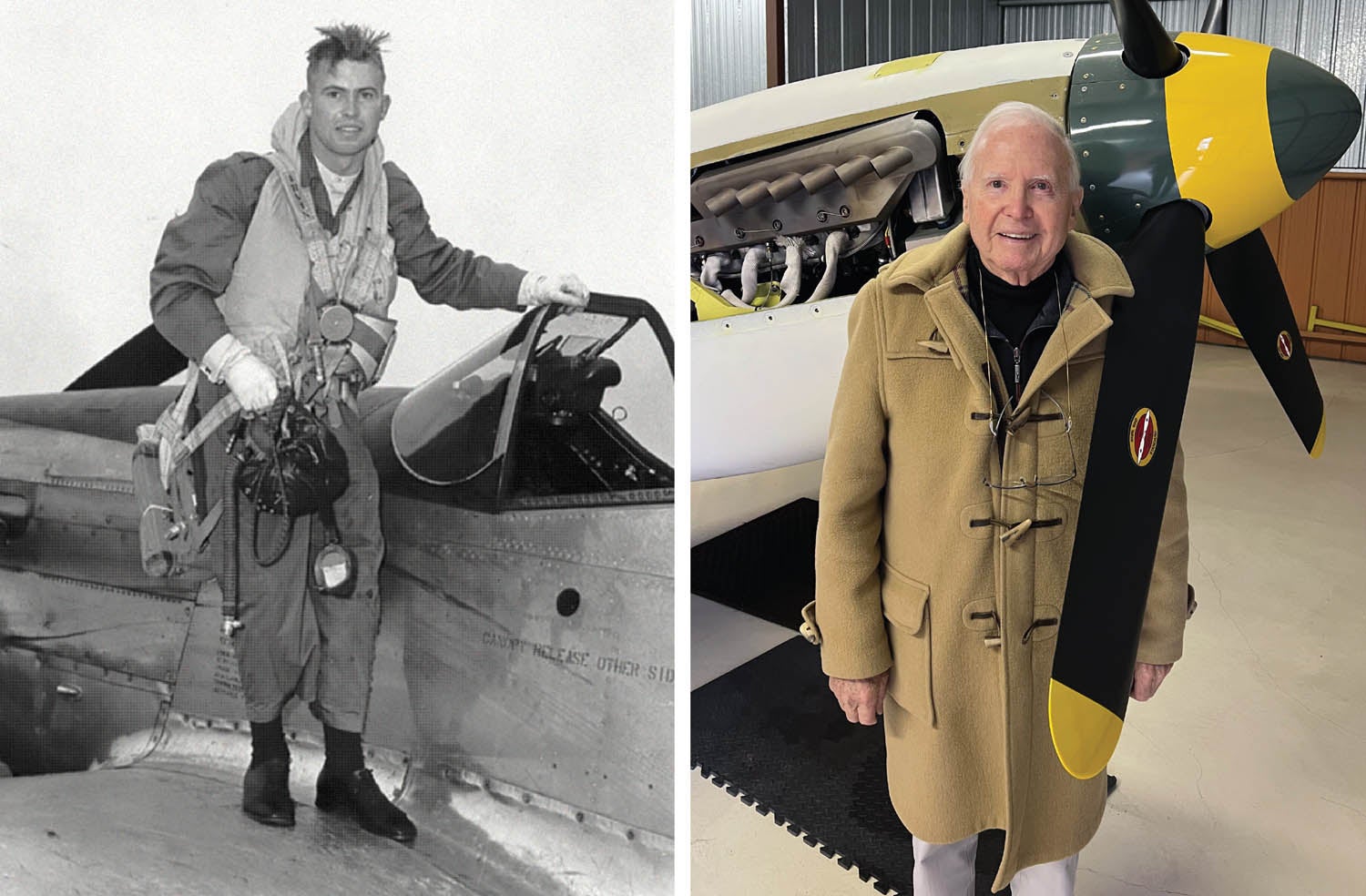

Ken Melvin is an accomplished pilot and endocrinologist from New Zealand who started flying 72 years ago. Some of his favorite memories surround his time spent flying P-51D Mustangs for the Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF). He explained that his squadron’s motto was “always attack,” pointing to a sticker on his RV-9A, the words forming around a Māori war club and Scottish dirks. Although the sticker is now positioned on a very different type of aluminum airplane, I got the sense the sentiment still rings true. Ken has accomplished so much with his life, really attacking it from all angles.

He learned to fly while in high school through an Air Training Corp scholarship, which granted him 40 hours in DH-82A Tiger Moths. The airfield was close to his boarding school, so he’d attend class then head out to fly. Tiger Moths have no electrical system and no tailwheel, just a metal tail skid. I can only imagine how glorious it must feel to recall flight training in this way: hand-propping a biplane and taking to the skies in an open, very cold cockpit, communicating by way of a rubber tube. Ken shared these delightful stories and I cringed at my own memories of learning to use a whiz wheel.

One of the more startling exercises Ken recalled was learning to restart the engine midair. The instructor would take Ken to altitude and switch the engine off, a procedure that proved quite sporty when the instructor slowed the airplane to stop the windmilling propeller. “How on earth are we going to get out of this?” he reminisced in a full Kiwi accent. “But then you enter into a dive and just gently tweak the stick to increase the angle of attack across the prop, which spins it and starts it up and the engine bursts into life again.”

Ah, yes. They certainly don’t make pilots like they used to. After high school Ken did his Compulsory Military Training (CMT) at the RNZAF Station Taieri in the South Island of NZ, continuing training in Tiger Moths. Following basic training, he was posted to RNZAF Wigram in Christchurch for advanced training in Harvard AT-6s, which he said were delightful and easy to fly. He was fortunate in that all of his instructors had been in combat in Europe or the Pacific flying Corsairs, Spitfires and Mosquitos, so they knew all the tricks of the trade. “People would teach us all of their tricks,” he said. “It’s a shame all of those skills have gone now ’cause we don’t need them anymore.”

I couldn’t agree more. My mind summons countless paper nav logs. An important discipline in its own right, but these haunting squares didn’t exactly aid in pilotage. I’ve also always had GPS as a safety net. Aside from learning valuable navigation tactics, Ken also learned formation flying and aerobatics and met experienced mechanics who taught him how to look after his engines. Training was very intensive. He attended lectures every morning and flew every afternoon. His least favorite part about training was sitting in the Link Trainer. With this device the pilots learned instrument procedures, which often resulted in them trying to drive it off the table and smash it into the ground. Now this I can relate to! Tomfoolery in the simulator.

“The sky was full of Harvards,” Ken went on. “While I was airborne one day I saw two Harvards crash head on. The wings came off and both fuselages hit the ground like darts and buried themselves in very deep holes. I drove over to have a look at them. Both guys had jumped out and I saw one descending in a parachute with the wing fluttering above him.”

If you haven’t deciphered it by now, military training is advantageous in that it pushes you past your breaking point. You fly the envelope and beyond in every airplane so that nothing comes as a surprise later. “It was a wonderful training and the guys that taught me, I owe them so much, because they’ve kept me alive,” Ken said.

An Immortal Age

After 260 hours in Harvards, Ken graduated top gun as a fighter pilot and posted back to the RNZAF Taieri, flying P-51D Mustangs. Here’s where the real fun begins. Most of the other pilots in his squadron had just come out of combat, flying things like the Hawker Tempests with the Napier Sabre H-24 3000-hp engines. (Think of the Sabre as two horizontally opposed 12-cylinder engines stacked one atop the other.) Ken listened in awe at the more experienced pilots’ tales and unknowingly stored little snippets of information away, which would later become useful. At last, it was time for him to solo the Mustang.

“One had to sort of read the manual before flying the Mustang,” he admitted. “Well, at 19 you think you know it all and you don’t take much interest in reading a dry old manual.” He climbed into the cockpit, full of excitement, entranced by the smell of 130 octane and sweat, something he described as the smell of a real cockpit. The squadron leader knelt on his wing and made sure he knew where all the switches were. “You haven’t really much idea, but you’re not worried because you are immortal at that age,” Ken laughed.

He got it fired up and taxied out to do his run-up. Then it was time for takeoff. The experience that followed was like nothing he’d experienced before, or since. “It was overwhelming. Your brain shuts down and you’re along for the ride,” he said. “For the first couple of minutes, I was just a passenger.”

Although he had a couple hundred hours in the AT-6, it didn’t fully prepare him for this. He flew for an hour or so and got a feel for it before landing, which proved to be no big deal. Gradually he got used to a whole new level of performance. “If you give a teenager 1600 hp, six 50-caliber machine guns and six 5-inch high-speed rockets to go play with, you’ve got a real menace,” he laughed. “It was the greatest fun I think I can ever remember.”

A New Discipline

When the RNZAF acquired de Havilland Mk. 52 Vampire jet fighters, Ken’s squadron was temporarily transferred to Operational Conversion Unit, Ohakea, for jet training. The main difference between the Mustang and the Vampire was the incredible silence of the jet and slow spool up of the turbine. He said it was a delight to fly, but never as much fun as the Mustang, largely due to fuel management. It burned 300 gallons of fuel an hour—5 gallons a minute. Ken explained that if you were running low on fuel when you returned to the airfield you could simply fly over at 25,000 feet, throw out the dive brakes, point your nose at the tower and come down vertically at 15,000 feet per minute, desperately trying to keep your ears clear. Did his commanding officer approve of this? Not exactly.

“If you haven’t been called before the commanding officer at least twice for overconfidence, you really haven’t enjoyed your flying to the max,” he smirked. “And I was indeed called twice: once in the Mustang and later in a jet when I landed with only 5 gallons left, which was 1 minute.”

After a brief stint flying Vampire jets out of RNZAF Ohakea, Ken was posted to the Reserve, where he flew Mustangs with the No. 4 Squadron. He also started medical school. “I would go up in a Mustang and pull contrails at 35,000 feet, come down and land and then go to lectures at medical school and look out the window and see my contrails,” he laughed. “And I was paid to have all that fun!” Ultimately, wear in the undercarriage trunnion bearings exceeded specifications and lacking replacement parts, all RNZAF Mustangs were withdrawn from service.

His training as a physician and endocrinologist extended over 14 years, in NZ and subsequently in London. He was then invited to a faculty position at Tufts University Medical School in Boston, with a specialist practice in endocrinology, and became director of the clinical research unit at the New England Medical Center. There, his research, in conjunction with Professor Armen Tashjian at Harvard, led to the first discovery of the hormone calcitonin in the human body. They found that this hormone was produced by a specific type of thyroid cancer that was often familial. Ken developed a blood test that allowed early diagnosis, which was the first time any cancer could be diagnosed in this way. As a result, many family members, including infants born into affected families, were diagnosed and successfully treated surgically.

Ken was then recruited to a newly endowed chair of medicine at St. Vincent Hospital and professor of medicine at Oregon Health Sciences University, in Portland, Oregon. He visited Portland and was enamored with the clean wide streets, rhododendrons in full bloom, smiling faces and geography that reminded him of New Zealand. He served as chief of medicine and Brill professor at Providence St. Vincent Hospital for 31 years, retiring in 2003.

“Hormones have been at the heart of a most rewarding and successful academic career, but when it comes to hormones, nothing in this life surpasses the adrenaline-packed joy of guiding a Merlin-powered Mustang high in the sky,” he said. “That was indeed a rare privilege.”

After moving to Oregon, Ken took a drive with his wife and children one Sunday afternoon and ended up at the Aurora airport, where he saw a tiny airplane taxi out and take off. He immediately knew he had to have one of these small airplanes, which was none other than an RV-4. He built one but after his late wife, Lily, got her pilot certificate she no longer enjoyed riding in the back so Ken parted with the RV-4 and purchased his RV-9A out in Arlington, Texas.

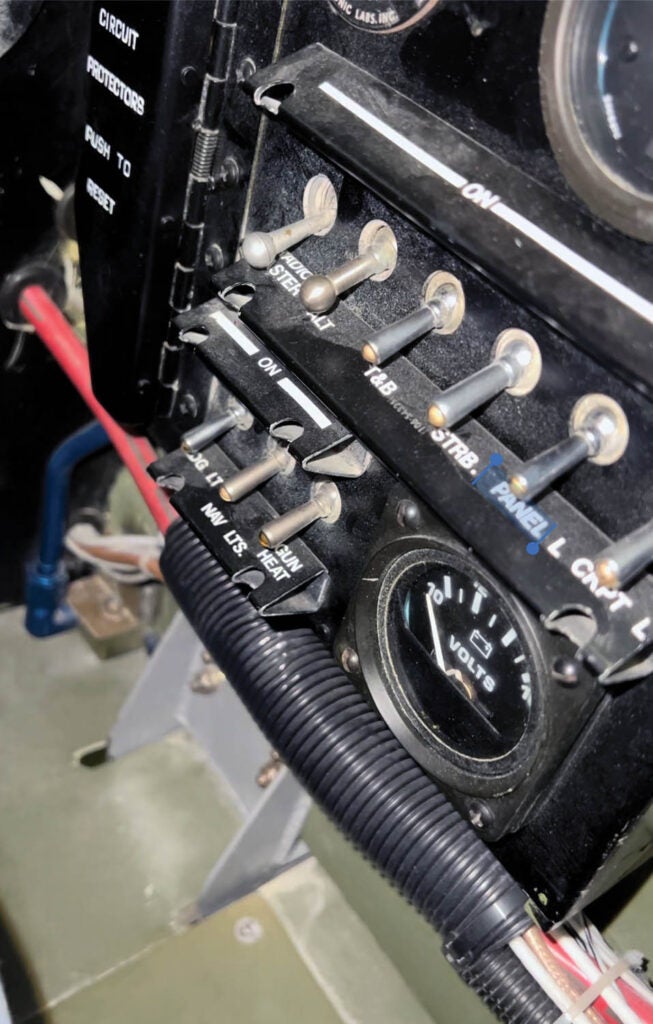

He also built a 2/3-scale FEW Mustang, which he’s been working on for nearly 25 years. It has a small-block Chevy V-8, a 383-cubic-inch stroker rated at 454 hp, turning a scale replica four-blade Whirl Wind propeller produced specifically for FEW. Unfortunately, Ken’s reached a point where he’s physically unable to finish it so someone else will need to take on this labor of love. It’s currently up for sale.

“Some of my happiest hours have always been in association with a Mustang, and so this was sort of continuing the association, in a different way, building one that was as close as I would get to a real Mustang ever again,” he said. “It took me a long time, but I loved every bit of it.” I may not have been granted the same flight training experience as Ken, but after meeting with him I did have a new sense for how I want to live the rest of my life. Always attack.

Photos: Ariana Rayment and Ken Melvin.