Back when I was a young ’un, older pilots cautioned me that the faster reflexes of youth and my more-recent training may not provide as much benefit as I might expect. They told me, “Old age and treachery will overcome youth and skill.”

Back when I was a young ’un, older pilots cautioned me that the faster reflexes of youth and my more-recent training may not provide as much benefit as I might expect. They told me, “Old age and treachery will overcome youth and skill.”

Now that I’m hitting the big seven-zero, it’s of more than just academic interest. Are my skills slipping with age—and does my greater experience help me compensate for it?

Let’s take a look.

Data Sources

The NTSB accident database includes the age of the pilot(s) involved in an accident. While the age of each pilot isn’t included in the FAA airman database, generic pilot age data can be found via the U.S. Civil Airmen Statistics web page.

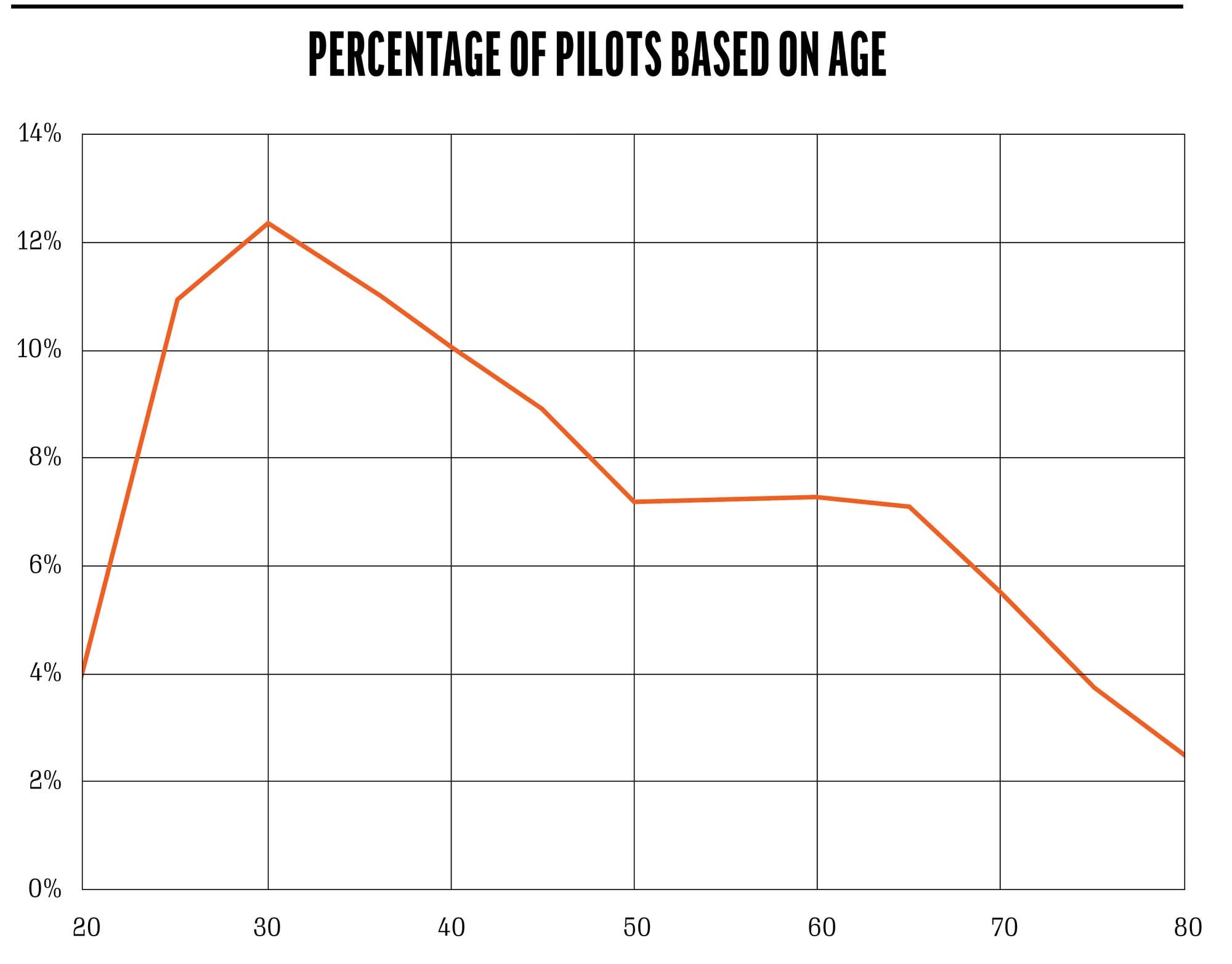

Figure 1 shows the age distribution from the airman database. About half of pilots are age 40 or less. Easy enough to combine the age data from the NTSB accident database to determine the relative rate of accidents within these time groups.

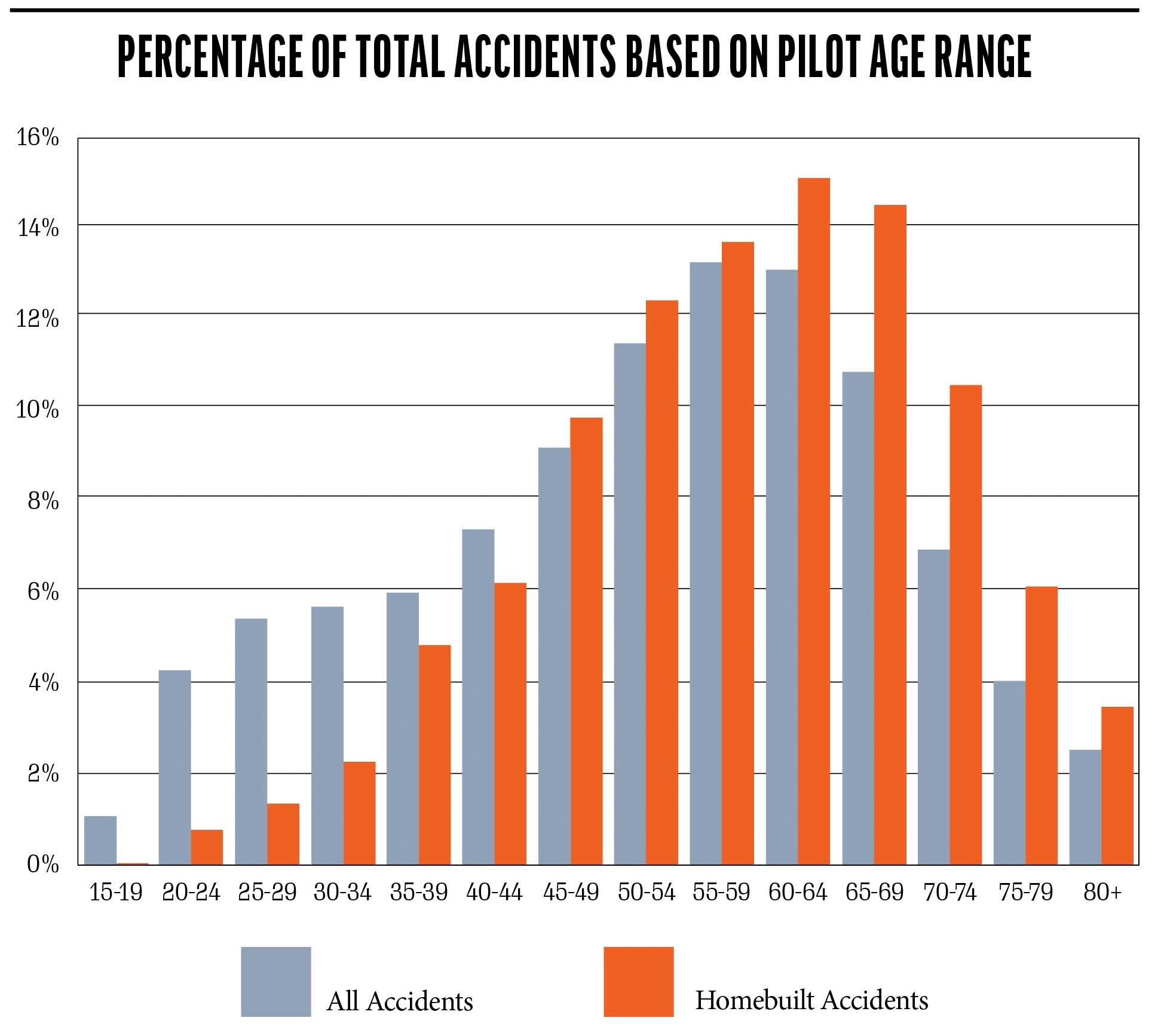

Figure 2—well, it looks pretty scary. Pilots in the 55–59 year group comprise about 7% of the total population but suffer over 13% of the total accidents?

Don’t despair, fellow old-timers. There’s another factor here.

Flight Time

What Figure 2 doesn’t allow for is the total flight time flown by the people in the age groups. Unfortunately, there doesn’t seem to be any data available regarding the median annual flight time versus age. The annual FAA General Aviation Survey includes estimates for annual flight time, but it’s not broken down by the age of the pilots.

Would it make a difference? It might. Recreational flying isn’t cheap and older pilots are likely in a better financial condition to afford it. Their children are out of college, houses/cars are paid off, etc. For those flying professionally, they’ve been in their jobs long enough for wages to rise and to have enough seniority to be able to fly as much as they wish.

However, “likely” and “may” aren’t statistics. We don’t know how much these factors contribute to older pilots flying more, or whether it just describes a few lucky (older) individuals.

Figure 2 gives us another clue. Note the relative involvement of younger pilots in homebuilding accidents. It’s much lower in the pre-40-year-old period, but the percentage of accidents involving homebuilt pilots is much higher as age increases. It’s another clue that actual hours flown by each group is important.

Sadly, again, that kind of data just isn’t available.

But we should be able to proceed using a different analysis method, with a different data source.

The Basic Issues

Let’s step back a bit and consider the factors we’re looking for.

The first point is the effect of aging on human reflexes. There’s no question they slow as we get older. The question is, when does this slowing affect pilots to the extent that it results in accidents that might have been avoided in their youth? Do older pilots experience more accidents due to stick-and-rudder errors?

Aging can also affect the decision-making process. Are older pilots more likely to mismanage fuel, forget to put the gear down or continue VFR into IFR conditions?

Since 1998, I’ve analyzed homebuilt accidents and collected the statistics on precisely those situations. About 40% of homebuilt accidents are due to what I call “pilot miscontrol,” which refers specifically to the kinds of mistakes pilots might make when controlling their aircraft.

In addition, another 15% of homebuilt accidents are due to pilot judgment issues. These include fuel exhaustion or mismanagement, out-of-CG conditions, VFR into IFR cases and buzzing. A common term for these errors is aviation decision making (ADM).

Together, pilot miscontrol and pilot judgment encompass what we’d ordinarily call “pilot error.” And we can use the NTSB accident pilot age statistics to determine whether older homebuilt pilots suffer an increase in pilot error accidents.

This gets us around the lack of information regarding annual flight time. What we look at instead is the percentage of accidents due to pilot error in each age group.

Interesting Results

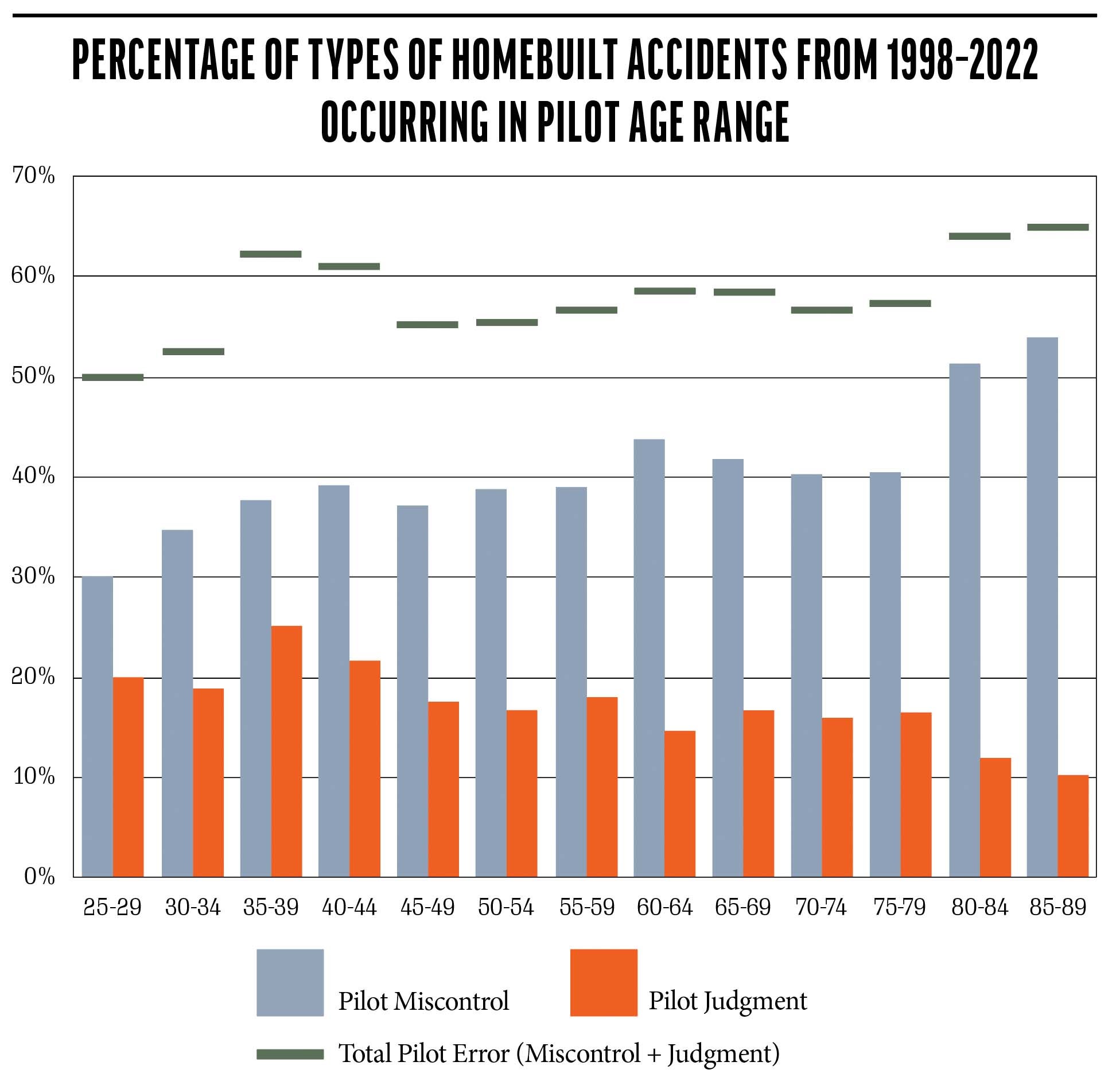

Figure 3 shows the results. The two bars for each age category indicate the percentage of the accidents occurring to pilots in that age range. The first bar is the accidents due to pilot miscontrol and the second bar shows the results for judgment issues. The ages run in five-year groups, from 25 to 89. Data exists for younger than 25 and older than 89, but there aren’t enough accidents for reliable results. There are, in fact, just 39 accidents in the 85–89 year group. This is lower than my preferred 50 accidents but close enough, I think, to include.

The horizontal lines above each set of bars show the total pilot error—defined as miscontrol plus judgment.

The pilot error rate rises through about age 44, then tapers off and is mostly constant through age 80. Above 80, the rate jumps again, to only a little higher than the age 35 to age 44 rate.

Even more fun, look at the pilot judgment results over the time period. After it peaks around age 40, it generally decreases. Stays pretty flat past age 80, too. Doesn’t look like older pilots’ ADM is failing.

By age 80, though, it’s obvious that pilot reflexes are being affected. The pilot miscontrol rate is starting to climb. However, it is almost compensated for by a rather steep drop in pilot judgment accidents. Both these trends continue in the 85–89 age set.

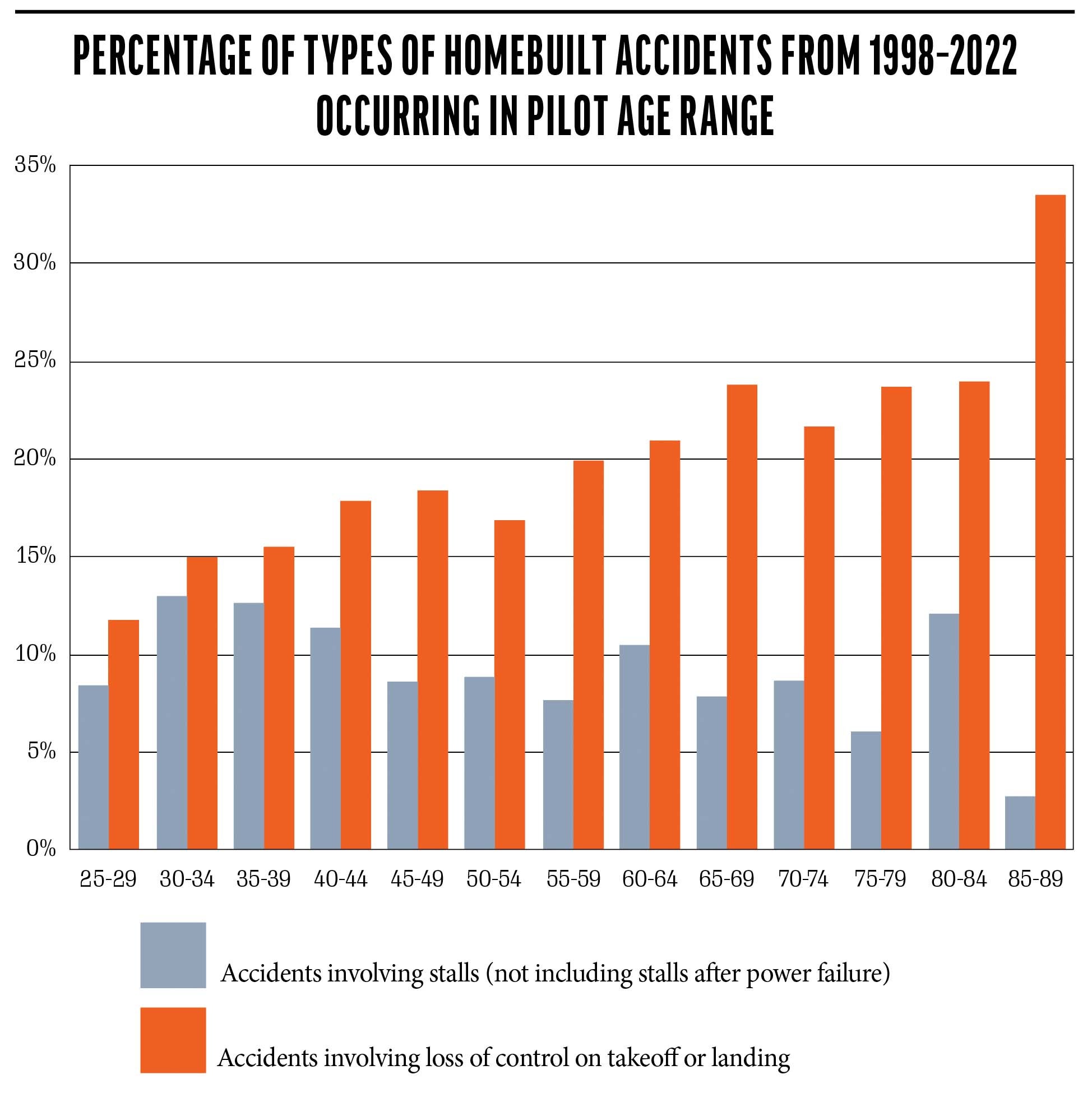

Figure 4 provides more insight. It plots the relative occurrence by age group for accidents involving inadvertent stalls (when not related to a loss of power) and a loss of control during takeoff and landing (including misjudged approaches). By the time the pilot ages are between 85 and 89, fully one-third of the accidents were due to the pilot losing control on takeoff or landing.

On the plus side, the incidence of inadvertent stalls tends to decrease with age. We seem to retain the “feel” for flying the aircraft; we just aren’t maintaining control as well during takeoffs and landings.

What Does It Mean?

Looking at the data, it appears that age 80 seems to be the key point. Figure 3 shows the overall pilot error rate staying about the same up until that age, and there’s the rise in stall-related events starting at that age as well.

So, if you’re 80 or over, should you hang up your helmet and goggles? Get prepared for playing pinochle with your fellow octogenarians?

Not at all. These are statistics that predict the results for thousands of pilots. It doesn’t mean that you are about to undershoot your landings or stall out on takeoff. It means that some percentage of pilots exhibit problems at higher ages.

Nothing says that you fall into that percentage. You may well have better than average cognitive function that precludes these kinds of problems—at least for now. Equally, though, there are some pilots who exhibit issues earlier than others.

Statistics like these are closely examined by one class of people: insurance actuaries. Many folks have reported having problems getting insurance when they reach their 70s or 80s. It may not be fair. But the industry is notoriously risk-averse.

Wrap-Up

A few months back, a friend sold his beloved RV-7. He was a former coworker; he’d discussed his post-retirement plan of building the airplane and flying all over the country. I’d watched the airplane going together at our home field and remember the pride when he started living the dream. Over the years, his plane has appeared in several of the articles I’ve written for this magazine.

But as he aged, he felt he was having a harder time “staying ahead” of this high-performance airplane. A hard-headed engineer, he finally reached the point where he just couldn’t justify the risk. His plane sold quickly and is now with its new owner on the other side of the country.

It’s a hard decision to make. Looking forward, I don’t relish having to make it for myself. I’m flying as a Sport Pilot; the FAA isn’t looking at my cognitive abilities.

But at some point, we all have to decide. The alternative is a bent airplane and upended lives.

Do you think, “Well, I’ll be dead and it won’t matter”? There’s a ~75% chance that you won’t die in the accident. Our older bodies don’t heal as well. Spending your final years in a wheelchair or hospital bed after a crash is a real possibility. I want to keep flying, but I want to continue walking on my own two legs even more.

Close calls where a crash is avoided might give you reassurance that your reflexes are still intact, but perhaps one should look into why those close calls are happening. Similarly, if family members or friends are expressing concerns about your abilities, maybe you should consider them more seriously.

It’s up to you to determine when your skills have slipped too much.

Photos: Ron Wanttaja, FAA and NTSB. Charts: Ron Wanttaja.

Ron,

Excellent article.

However I do take exception to an assumption you made. “ Recreational flying isn’t cheap and older pilots are likely in a better financial condition to afford it.” You are correct about flying isn’t cheap. But because I am older I am Iikely to be in a better financial condition is contrary to what I am observing and experiencing. Just turned 70, 53 years of flying, Part 103 is looking more affordable every day if want to continue my adventure of flight.

I think this is a gross mis-use of percentags, to warp the actual numbers.

He shows “percentages of accidents” in the varoius age ranges,

but does not show that there are many more pilots in the 40s, 50,s 60s than in 20’s or 90’s

when he says 35% of the accidents by 80 yr pilots are from takeoff/landing control,

that may be ONE accident if the 80 yr class only had three total.

But 100 young punks could have wrecked … and their percentages would be smaller…

There needed to be ACTUAL NUMBERS in those age groups for this to have any meaning.

and for the record, I am 75, retired cfi (military long ago) and still fly, but only with other pilots.

I am not questioning that old guys like me have lost some skill, but this data is spurious…

Certainly, if one is dealing with just a handful of accidents, the sample size is important if you’re reporting based on percentages. If you’ve got five total accidents and three of a given cause, that’s a 60% rate. But if just ONE more accident occurs, it skews the rate badly.

As I say in the article, I normally require a minimum of 50 accidents before analyzing the percentages. This means that each accident is no more than 2% of the total. Again, as I said in the article, there were just 39 cases in the 85-89 year old set, but I thought it was still a large enough sample size to make it worthwhile.

Please note that my numbers are not the percentage of PILOTS having a given type of accident, but the percentage of the TOTAL ACCIDENTS that were of the given type of accident. Twenty accidents in a 100-accident set provide the same results as 200 accidents with a 1,000-accident set.

Trying to compute the percentage of pilots wouldn’t give valid results. We know how many pilots are in the 85-89 year-old bin, but that’s just the number pilots in the FAA roster. We don’t know how many are actually actively flying. When pilots stop flying the accident rate goes down….

here’s an example of how percentage statistics can be misleading —

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GKLu8Oq5BXY

I wonder if the loss of control on takeoff and landing for us 80+ pilots is due to more of us flying taildraggers? That seems to be what I observe.

You might be on to something there. A few years back, I examined the accidents involving three groups of pilot experience. The results were interesting, with the pilots with 20,000+ hours experiencing relatively more loss of control accidents on landings. And the reason for THAT was taildraggers; of 19 loss of directional control accidents for the 20,000+ set, 14 involved taildraggers.

Have a couple years on you Ron but enjoyed the article. One observation that I have discussed with my insurance broker is who is safer, builder or 2nd owner. Insurance companies believe it’s builder. However in searching for RV-8 for over a year, ran into many who spent 8 years or more building and now only fly 20 hours per year, some even as low as 10. So my 125 hours in 8 (plus another 125 in Columbia) make me think I’m safer than the builder.

Flying more hours in a year will definitely make you safer. However, I did an analysis several years ago on builder vs. purchaser accident rates. A lower percentage of purchasers have accidents within the first 50 hours.

However….

Those accidents tend to happen earlier. With flown by the builders, about 14% of their accidents happen in the first five hours. That’s compared to people who purchase homebuilts… over 19% of their accidents happen in the first five hours! A working assumption is that the builder of a homebuilt will be motivated to get as much training, etc. as possible before their first flight, but the purchasers just brush it off, saying, “Hey, it’s tested…what can go wrong?”

By the way, that 14% and 19% is the percentage of ACCIDENTS, not the percentage of all homebuilt aircraft.

I ran an analysis on this several years ago, it was published in KITPLANES in 2019. Available online:

https://www.kitplanes.com/buying-trouble-purchased-homebuilt-accident-rates/