One of the nice things about living in Southern California is the weather. Very rarely does it get so cold that you need to preheat your engine. Today, however, I live in Northern Nevada and while it’s not as biting cold as Alaska or Canada, the winters get cold enough for long enough that having some sort of preheater is a necessity—at least if you want to fly on a regular basis.

My first exposure to aircraft engine preheating was from watching Ice Pilots on TV. The show ran from 2009 to 2014 and followed the trials and tribulations of a small airline called Buffalo Airways. To this day, they still operate mostly WW-II era aircraft plying cargo to the Northwest Territories of Canada. As you might imagine, when operating in sub-zero weather, engine preheating and heat conservation (such as during connecting flight layovers, etc.) is a major problem. The Buffalo crews use anything and everything to deal with the issue: compact ceramic space heaters in engine bays, dolly-mounted Frost Fighters and, the mother of all preheaters, diesel-powered Herman Nelsons. In one memorable scene, a crew missed a critical connection because they couldn’t thaw out their engines using the less capable Frost Fighters. This prompted a variety of criticisms from the maintenance crew for not taking Herman Nelson heaters: “Using a Frost Fighter (when it’s that cold) is like trying to cook a hot dog with a lighter.”

If you’ve never seen Ice Pilots, it’s worth looking up on your streaming service or at least check out clips from the show on YouTube. A typical one-hour episode is about 70/30 miscellaneous ground ops versus flying—but that’s still more flying than you can find anywhere else on TV!

Which brings us to this month’s home shop project: my homage to Ice Pilots and their Herman Nelson heaters. I call mine the Pee-wee Herman. It was made from a portable space heater. The idea is not new. My buddy Kevin King has been using one for years, but his heater is an older, industrial style unit with a metal case. Nowadays, small ceramic element space heaters for home use are much cheaper. In fact they are so affordable that you can DIY a small preheater for almost nothing. Putting mine together took a couple of hours in the shop and some home-center parts, including three feet of semirigid heater duct hose ($12 to $17 at most home centers), an elbow ($8) and a couple of hose clamps. I paid $30 for the space heater during a closeout sale. Similar units sell new for between $45 and $80. Most heaters in this price range have two or three fan settings and heat outputs. Most models also have a tip-over sensor that will automatically shut off the heater if it gets knocked over.

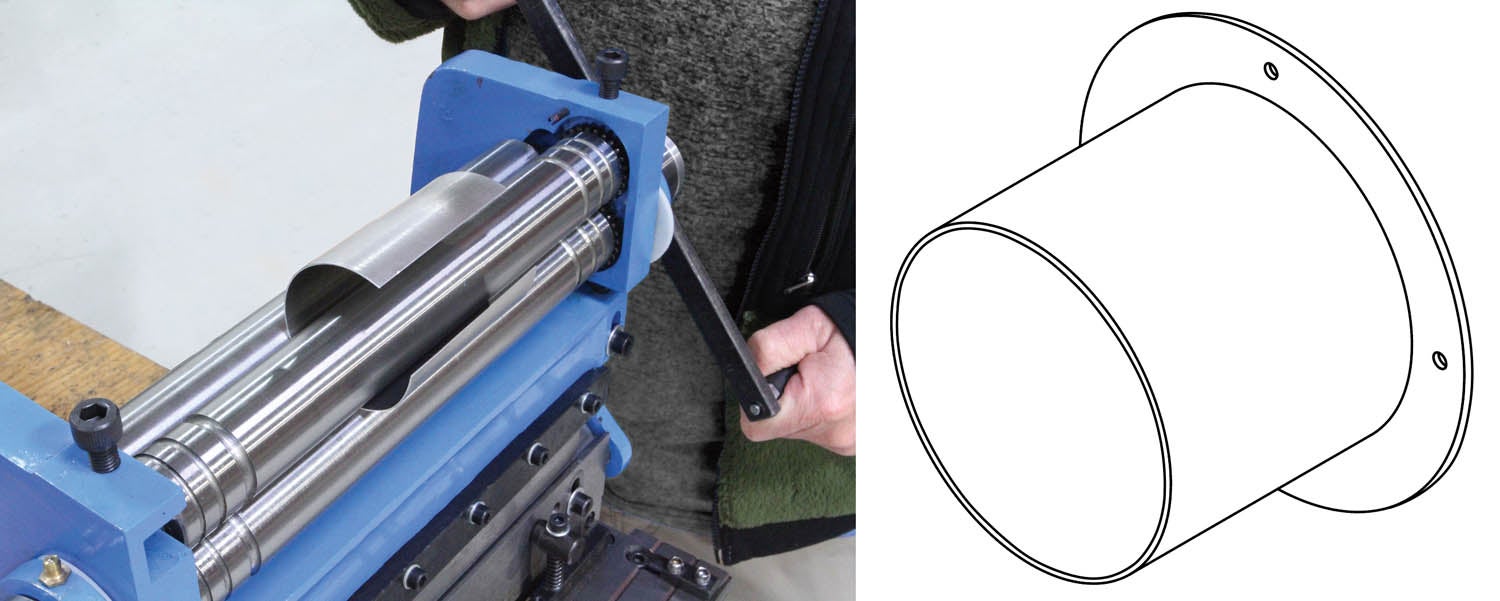

The shop time was spent fabricating a suitable way to attach the 4-inch-diameter ducting to the heater grille. I used a slip roll to form a 4-inch “pipe” from 18 gauge (0.050 inch) cold-rolled steel sheet. A mounting flange was cut from the same material by drilling a series of small holes to core out the center circle and a band saw was used to cut the outer circle. Hand filing cleaned up the rough edges. Alternately, you can use 20- or 22-gauge cold-rolled sheet. You can buy an 8×24-inch sheet of 22-gauge steel for about $15 at most home centers, and you can cut the parts out with hand shears or a nibbler and rivet everything into shape.

On mine, I had my friend Billy Griggs stitch weld the flange to the pipe (see “How the Bead Goes On,” January 2022). A continuous bead would have been overkill and, on such thin sheet material, more than likely would have caused the flange to warp. A coat of VHT high-heat exhaust pipe paint completed the job.

The flange was riveted to the heater grille. My design allows some of the heat to bypass the duct, which I thought might be a good idea to keep the unit from overheating and shutting off. After messing around with the semirigid hose and the mounting flange, I added a 45° heater duct elbow to make it easier to aim hot air at the oil sump.

To be sure, the Pee-wee Herman has limitations. It’s definitely not suitable for arctic conditions like the Northwest Territories or probably even Wisconsin for that matter. But it has proven itself for temperatures down to 25° F.

The main point of an engine preheater on an air-cooled engine is to warm up the oil. But it also helps to heat up the engine compartment, including the battery—all of which helps make the engine easier to start. On my plane, with this setup, the engine oil temp goes from near freezing to 40° F in about an hour.

One caveat about using a preheater: You should only use a preheater if you intend to start your engine and run it to normal operating temperatures. Running a preheater without starting your engine could cause condensation to form. Not a good thing. An explanation of that issue as well as the benefits of preheating can be found in an article written by Jeff Simon, titled “Aircraft Maintenance: Proper Engine Preheating,” on the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA) website.

That’s it for now. If it’s not too cold, it’s time to get back in the shop and make some chips!

I built a pre-heater like this last year.

December and January in Northern California are not cold, but the early mornings can be close to 32 degreesF.

I’m not keen on starting my engine at these temps, so I set up the pre-heater the day before I plan to fly, on a timer.

The 1,500 watt unit blows hot air up through the lower cowl opening, [ avoiding the carb, since the air is 150 degF+ ]. I drape a sleeping bag over the upper cowl, covering the air inlets.

After 4 hours of preheat the oil and cylinders are close to 85 degrees.!!

After engine start, the taxi to the run up area has my oil over 90 degrees, so it’s a quick mag check and off I go.

It also saves some fuel, not having to run at 1,500 rpm for 10-15 minutes to get the oil to minimum temp.!!

Find an old wool blanket, drape over cowl cut to fit. Place a mylar survival blanket over the wool blanket cut to match stitch together. Drape over cowl this will reduce preheat time and also will keep engine warm during a brief shut down on a pit or coffee stop.