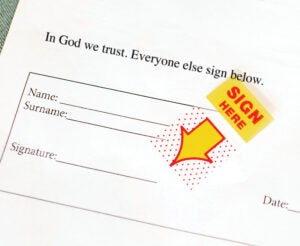

Most of us have been in a Mom and Pop café or shop, usually out in the country, where the wall on one side of the cash register is covered in bounced checks, and the other side hangs a plaque that reads, “In God We Trust—All Others Pay Cash.” Folksy humor aside, what is often the case is that the proprietor at one time accepted checks. In time, abuse of this trust caused them to rethink the policy.

Most of us have been in a Mom and Pop café or shop, usually out in the country, where the wall on one side of the cash register is covered in bounced checks, and the other side hangs a plaque that reads, “In God We Trust—All Others Pay Cash.” Folksy humor aside, what is often the case is that the proprietor at one time accepted checks. In time, abuse of this trust caused them to rethink the policy.

What does this have to do with Experimental aviation? Like just about every facet of the lives we live, our aeronautical world is built upon many levels and layers of trust. For someone in the Experimental world, it is actually possible for someone to design, build, maintain and operate their own airplane, all by themselves. Some have built their own engines of their own design. Rob Hickman of Advanced Flight Systems built his own avionics. Still, the sampling of individuals who can accomplish it all without requiring trust and faith in the efforts of others is not only incredibly small but also not without many unfortunate endings.

Big Iron Trust

In the airline world, it is impossible for pilots to operate without a massive load of trust in the direct and indirect efforts of the hundreds of individuals that it takes to get every flight safely from Point A to Point B. Designers, builders, maintainers, dispatchers, fuelers, weather forecasters, security personnel, passengers, fellow crew-members and even regulators all play a pivotal role that is hard if not impossible for an individual aircraft commander to oversee and verify all of their collective actions while checking his or her own work in the process. Each link in the chain is essential.

Pilots need to trust that a fatal design flaw isn’t going to take down their aircraft years later. Pilots need to trust that a controller isn’t going to cause an airplane arriving in a blinding sun to land on an airplane holding in position on the runway. Pilots need to trust that a mechanic didn’t fail to secure a row of fasteners on a critical control surface that is out of view of the crew. Pilots need to trust that a manufacturer, in the course of a major design refresh, hasn’t failed to provide key information on new systems functions. Pilots, lacking clear information, will assume the new model acts like the old model—and they trust they will not be misled.

Rules of Experience

All of the aforementioned examples and many similar ones have happened, and fate being the hunter that it is, additional such events will likely continue to happen. In each case, exhaustive efforts are made to revamp the process with sometimes onerous new bureaucracy to make the operation “better.” Some changes make such total sense as to elicit a chorus of, “Why didn’t we think of that before?” Usual answer: “Because the situation was never considered and had heretofore never been an issue.” In the case of the infamous manufacturer model refresh turned nightmare, the ensuing evaluation and investigation ignited an expensive, lengthy and microscopic review of the elements at hand, ones that resulted in numerous changes of procedure in the industry.

The flip side of the common-sense examples are well-meaning but overreactive responses—such as when flight crews were forbidden to carry nail clippers into flight decks equipped with federally mandated crash axes. Pilots were trusted with the ax, heck even trusted with the yoke, but not trusted with the nail clippers. That one is still a head-scratcher.

Trust is still part and parcel of any operation, but when violations of trust occur, what then takes higher priority is encapsulated nicely in the phrase made famous during an exchange between Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev—Doveryai, no proveryai, which translates into “trust but verify.”

Needless to say, all things considered, we are still functioning amazingly well in spite of all the incidents of the past. Aviation itself, and airline operations, in particular, are phenomenally safe despite the failings, flailings and tailings of the imperfect human beings that comprise it. As much as there are safeguards in effect, there still comes many times where we are forced to put trust in others, or we go crazy trying to do everyone else’s job for them, and in the process live with the result of our own failings.

Closer to Home

Perhaps it’s the nature of aviation—and Experimental aviation especially—that basic trust in our fellow builders, kit manufacturers and suppliers has trended well above the norm. In the world generally, distrust and cynicism are true growth industries, but general aviation has kept more of the early “we take checks” mentality and personality than we should probably expect.

But it is changing. Buyers and sellers of kit parts on type-specific bulletin boards have to be increasingly careful of getting scammed. So-called hackers have become more and more successful “borrowing” a person’s profile and bilking trusting buyers of everything from wing sets to com radios. We have to get used to the idea of “trust but verify” in our person-to-person commerce and never let our guard down.

These kinds of scams are hardly new, and neither, really, is the next one. But this hits especially close for me. As the author of our buying-used segment on the RV-10, I contacted readers and owners for their feedback on the design. It’s part of our reader service here to provide as many voices as we can, so that you have as many data points as we can squeeze onto the page.

In this case, we had an individual who claimed to be an RV-10 owner that, we later found out, was not. The dishonest submitter’s name and details don’t matter. We’ve offered him multiple opportunities to “set the record straight,” but after being found out, the prankster is likely just looking for further recognition that we are unwilling to give. “It’s a good thing his comments were so anodyne,” my editor told me. “Nothing he said was offensive or contradictory to what others have said about the RV-10.” No, it was apparently just made up.

Nevertheless, we are putting some new guardrails in place to verify the ownership of those who claim to have owned or built airplanes in our reader-feedback section. A quick Google search plus a few moments with the FAA database and sites like FlightAware.com can tell us a lot. This experience was an eye-opener for me and, says the esteemed management of this place, the first time it’s happened in this context. And that is why there was no formal process in place: We didn’t need one. But all things change. It’s not that you can’t have trust in the Experimental aviation community, far from it, but, increasingly, that trust can’t be offered blindly.

Illustrations: Peter Jones, Shutterstock; photo: Shutterstock.

As Myron pointed out, there are people out there who want to be the expert regardless of their expertise. When I started working on my Long EZ in 1995 I got a lot of helpful suggestions from people, but about 2/3 were wrong or made up. I found that the guys who’d already “done it” were the only ones worth listening to. To keep from contributing to the problem I usually only offer advice about things I’ve done myself, and I sign my letters to forums with my relevant experience:

Ian Huss 0-320 Long EZ 1780 hrs.