Any pilot who has been flying for a few years has run into this situation: You cancel a trip for some reason—weather, most often—and as things develop, it turns out that you probably could have flown as you had planned. We tend to look at these situations and say, “Well that was a bad decision. I got that one wrong.” But this is absolutely not the right way to think about it. If you made a decision based on your own “go/no-go” criteria and the information that you had at the time you made the decision didn’t meet the “go” criteria, then your decision was a good one, regardless of how the day eventually turned out. A decision that turns out later to be incorrect isn’t a “bad” one, so long as you asked the right questions and looked honestly at the answers.

Sometimes, the universe throws you a curveball. Here’s an example.

I recently was making an elective trip from my home in western Nevada to Ely, out on the eastern edge of the state. I was going to meet up with my wife, a cave scientist who is doing work out there, for a Saturday trip to an interesting cave. I had a long-scheduled trip that had me leaving Reno very early on Monday morning and I really couldn’t miss it. The forecast was for afternoon thunderstorms across the state and I figured that I could fly out early Saturday morning and spend the day caving. If I couldn’t fly back that evening because the convective activity was too rambunctious, I could fly back early Sunday morning. The plan looked solid.

The pattern for the week supported the plan, though the predictions for the weekend were for an increased chance of thundershowers. Friday had a pretty good bunch of storms—not middle-of-the-country severe squall lines but lots of little storms with tops in the 40s and bases buried in mountains. It’s possible to pick your way through that stuff without hitting rocks but there are almost no bailout options except dry lakebeds—and right now the lakebeds are wet. In other words, it’s easy to paint yourself into a corner.

Friday Presages Saturday?

The afternoon storms on Friday hadn’t fully dissipated by evening, although there were plenty of slots that you could duck through between storms. The real question was what it looked like on Saturday morning at sunrise. The NEXRAD was showing a few splotches of green, which could mean that there were building cumulus or just a few spots of virga still dropping from the previous day’s dissipating clouds.

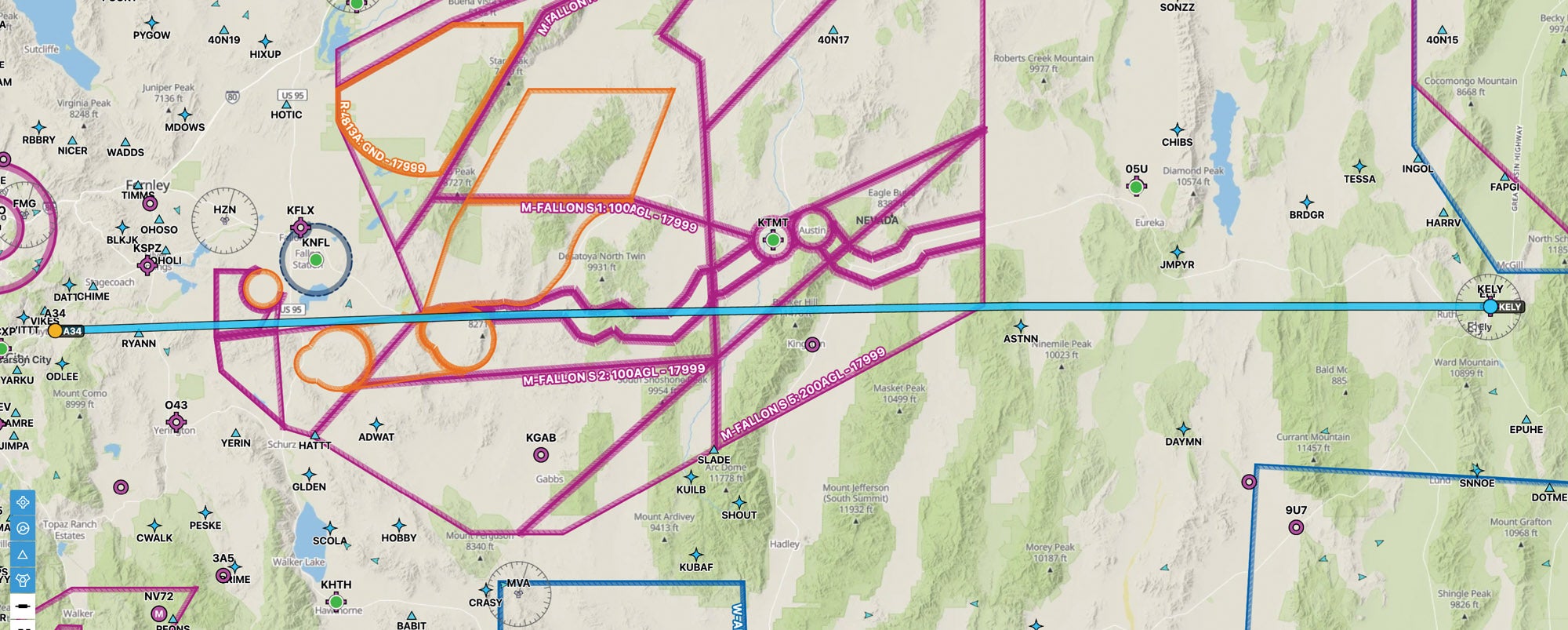

You see, central Nevada is one of the few places in the Lower 48 that doesn’t really have any NEXRAD coverage. It doesn’t have many METAR reports, either. It’s more or less the surface of the moon and the only way to know what is going on is to go have a look. It’s not obvious that this is the case because you will occasionally have echoes in the middle. But that means that you’re just seeing the tops of the clouds—while it could look green (light precipitation) you may just be looking at the moist high tops of a massive Level 5 thunderstorm and not know it.

With all that in mind, I looked at the sparse forecasts (basically what we had at home and what we had at Ely) for the next two days. Sunday looked the same as Saturday—storms in the areas at both ends by 2 p.m. local with scattered lower clouds in the morning. As the sky began to lighten at my end in the early civil twilight, I could see some clouds the sun was trying to poke through to the east, but it looked great where I was and at Navy Fallon (KNFL) about 50 miles east, so I launched.

Crossing the early morning desert, I was too low to talk to Oakland Center and the Desert Control guys (the military folks who run the restricted areas for Top Gun out of Fallon) weren’t awake. I had to stay low to navigate a narrow VFR corridor that allows you through the restricted areas—a Catch-22 because if you are high enough to talk to anyone who can tell you the restricted areas are hot (or cold), then you have to drop way back down to get through the corridor (if they are hot). Not a big deal, we do the corridor all the time. Once through the other side, I climbed for altitude.

There were dark clouds ahead. I could see between the clouds and the mountains for a long way east but could also see virga wisping below the clouds—meaning they were thick enough to be dropping moisture. The sun was alternately blocked and visible by the various layers. While it looked like I could go well south or north to get around, I was worried about the future.

If the weather developed like the day before, not only would I have difficulty returning this evening, Sunday morning could look just like this and my trip home then would be iffy. As I was thinking this over, I saw a lightning bolt about 40 miles away. It appeared to strike the ridge of the mountains one range farther east than the Toiyabes, the one I was about to cross. Onboard ADS-B NEXRAD was showing a wide area of pleasant light green most of the way between me and Ely. But that lighting didn’t lie and it didn’t come from green echoes! There was sufficient convection to make today look like yesterday.

The Decision

That was all I needed. Once you get into a repetitive summer pattern, it is easy to say that in the absence of frontal activity, what you see today is much like yesterday—and tomorrow will likely be the same. I dialed in a return course south of the restricted areas so I could stay at altitude and hightailed it for home, the clear smooth air welcoming me back.

The lesson was made clearer after landing. The radar on ForeFlight that same afternoon showed reds and yellows in all that green out there in the restricted areas. East of them, between the restricted areas and Ely looked clear, confirming the lack of actual radar coverage in that area. What you see isn’t what you get.

Here’s the main point: Useful trip information is not just reports of actual weather and forecasts from the National Weather Service computers. Information includes local knowledge, experience and anything else you can apply to make a decision.

In this case, all things pointed to the most conservative action being to turn around, which is what I did. It doesn’t actually matter what the weather does in the next 24 hours—I’ll be in position to make the next trip, so my design was good. Based on the information I had at the time, did I make a good decision in launching? Sure. I didn’t have a full picture of what was going on and I had a ready and easy retreat. It was OK to go take a look. Based on what I learned when I got to the Toiyabes and turned around, was that a good decision? Yup—because I now knew there was enough activity to make thunderstorms.

But later in the day, what happened? Couldn’t I have returned home just before sunset or the next morning? In this case, it doesn’t matter. The need to be back for the upcoming trip meant that I couldn’t take the chance of being trapped out east and so I made the right decision based on the information I had at the time.

Good pilots look closely at how things eventually developed and add that to our personal database of “if I see this, then it means that, most of the time.” We apply that knowledge as we’re looking at weather because that will help us to make better decisions under whatever circumstances and rules we are following in the future. Fly. Learn. Repeat.

Thank you for this article!! In the air, at the end, you will never regret being too conservative but you will always regret being too bold. Being too conservative has never killed anyone but being too bold or letting get-there-itis become the PIC has.