Oil changes can be messy. No matter how careful I am, oil always seems to drip onto and into the most remote crevices. On my Jabiru engine, the oil cooler is mounted just below the drain. You can guess that cleaning up is quite an exercise involving degreaser, compressed air, and what seems like half a forest worth of paper towels.

After the last oil change I decided enough was enough! I ordered a brass Curtis oil-drain valve from Jabiru USA. You can install the valve as a direct replacement for the drain plug, or use the included 90 adapter. This provides some flexibility to accommodate the variety of kits that use Jabiru engines.

A detailed sketch is not only helpful for making the part, it should be part of the builder’s records, or in this case, the maintenance log.

In the case of my Jabiru, I couldn’t use the adapter because the oil cooler bracket was in the way. But screwing the valve straight in created a situation where attaching a drain hose to the outflow nipple would risk getting burned by the hot exhaust shield.

My solution: Cut off 3/8 inch from the nipple and attach a low-profile elbow. Looking through various catalogs for a suitable elbow turned up no viable options. The Curtis elbow was more or less the right shape, but not compatible with being attached to the outflow nipple. So, it was out to the shop to come up with a suitable solution. After rummaging around the material bin and some head-scratching, I turned up a short piece of 1/2-inch thick aluminum and with it an idea for a clamp-on, low-profile elbow.

The elbow itself is relatively simple. You could make it entirely on the lathe, but since facing and drilling operations are easier and quicker on the milling machine, that’s how I did it.

When one machines a part from a solid stock, it’s called “billet machined.” This catchphrase distinguishes solid-stock parts from those made from “prepared stock” such as a forged or cast pre-formed blank. Making parts from prepared stock used to be the predominant method a few generations ago. But the abundance of high-quality billet material and high-speed CNC machining has made the use of prepared stock for machined parts more or less obsolete.

A few comments on the design before I get to the step-by-step. The hole for the outflow nipple on the Curtis valve has a flat bottom. This was done to help expedite the flow of oil. I made a Delrin plastic sleeve to go between the brass and aluminum parts. This eliminates any chance of galvanic corrosion, which can occur when dissimilar metals are in contact. All the hard edges were deburred. The final step was spray-painting it with a baked-on, ceramic, heat-resistant paint.

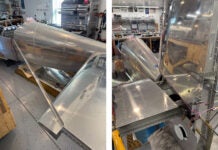

Below is the machining sequence from billet blank to final part.

3. The blind hole for the Curtis valve outflow nipple was done in three steps. Using a 3/8-inch bit, I drilled to a depth of 0.650 inch and then used a 3/8-inch end mill to flatten the end of the hole. I then used a 7/16-inch drill to a depth of 0.550 inch for the Delrin sleeve.

4. A 2-inch diameter, 100-tooth, 0.040-inch-thick slitting saw running at 250 rpm was used to make the kerf for the clamp.

7. With the body clamped in the 4-jaw chuck and the drain hole centered on the lathe axis, turn to 3/8-inch diameter to create the integrated pipe.

8. Chamfering the corner on the disk sander removes excess material and improves the clamping function.

9. The parts before assembly. The nylon sleeve eliminates any risk of galvanic corrosion by insulating the brass valve from the aluminum elbow.

10. On the top, the elbow is clamped in position to allow the valve to lock open. On the bottom, the valve is closed.

![]()

Bob Hadley is the R&D manager for a California-based consumer products company. He holds a Sport Pilot certificate and a Light-Sport Repairman certificate with inspection authorization for his Jabiru J250-SP.