This column is a continuation of common in-flight failures that I began discussing in the September 2024 issue. With today’s glass cockpits and all the associated bells and whistles that are part of them, it is easy to get task-saturated without some preplanned courses of action when presented with certain scenarios. Of course, the first action should always be to fly the airplane, no matter what. Then figure out the proper subsequent course of action. I’ve written about first-flight issues in past columns, so in this column I will address issues pertaining to airplanes that are out of Phase I.

If you are the original builder, there’s a good chance you understand the “normal” indications by the time you have amassed 100 to 200 hours in the aircraft. If you are a non-builder and new owner, it might take you some time to develop that clear normal-state picture. I’ve seen some owners keep such meticulous records that they sometimes end up chasing ghosts because a particular engine reading has changed by a few degrees. So, somewhere in between no records and recording every flight, there is a balance.

Of course, with nice glass panels, all the parameters are stored in the logs, so it is easy to go back and compare. But that should be done when you are back on the ground! Let’s discuss what actions you should take when issues arise while airborne.

What’s Going on With the Oil?

Those of us who learned to fly with simple analog gauges were always taught to pay attention to the oil pressure and oil temp indications, as the oil is certainly the lifeblood of the engine. The needle on those gauges was so wide that it covered a wide range. Most pilots never paid attention to the actual temperature or pressure, and instead just noted that they were “in the green.”

Today’s digital gauges with single-digit accuracy can sometimes cause stress or unnecessary actions when nothing is wrong. As an example, on long cross-country trips in the RV-10, I can watch the oil temperature change in unison with the outside air temperature. Sometimes, that can be over 5°. I’ve learned to always check the OAT first before getting concerned about oil temps.

However, if the oil temp has risen, and continues to rise from a known steady state, it might be time to think about some other indications that could support a problem. With the oil thinning as it gets hotter, the oil pressure indication usually decreases. During climb-out after a fuel stop on a hot summer day, it is perfectly normal to see oil temps that might be 20 or more degrees higher than normal and oil pressure 5 to 10 pounds lower. Lowering the nose to slow down the climb rate can usually help cool the oil (and CHTs). Obviously, it’s important to stay within the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Once cruise altitude is reached, the oil temp should decrease and oil pressure should start to increase. If that doesn’t happen within 5 minutes of level flight after reducing the power, it might be time to consider landing, especially if temps continue to rise. The oil is recirculating in the engine at around 3 to 5 gallons per minute, so changes in temp should happen quickly.

The sooner a decision is made to make a landing, the better the chances are that you will be able to land with power as opposed to making a landing with a seized engine.

Although you have made the decision to seek out a landing spot, it doesn’t mean that you should stop troubleshooting. I had this happen to me in a friend’s RV-10. There was an unlabeled knob on the panel, and I had no clue as to its function, as turning it in either direction caused nothing to change in the cockpit. After leveling off I was presented with a rapidly climbing oil temperature indication. After I made a turn back to the airport, I did a rapid sweep of the cockpit, asking myself what I could have done. When I came to that knob, I immediately turned it completely in the other direction, and in less than a minute I saw the temps decreasing. Yes, we had a pointed discussion when I landed. It turns out the knob controlled a recently installed oil cooler valve.

Bogus Fuel Flow Indications

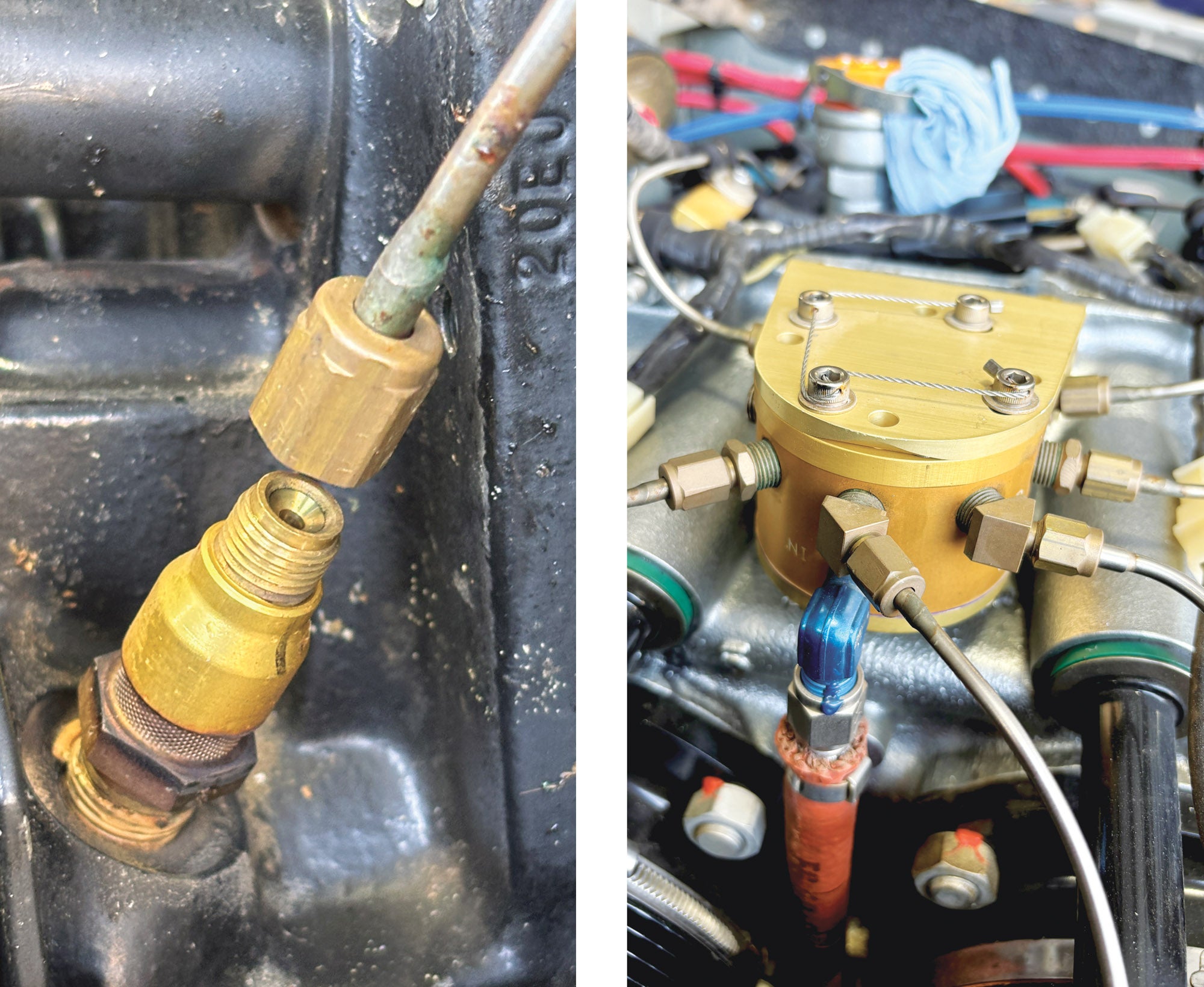

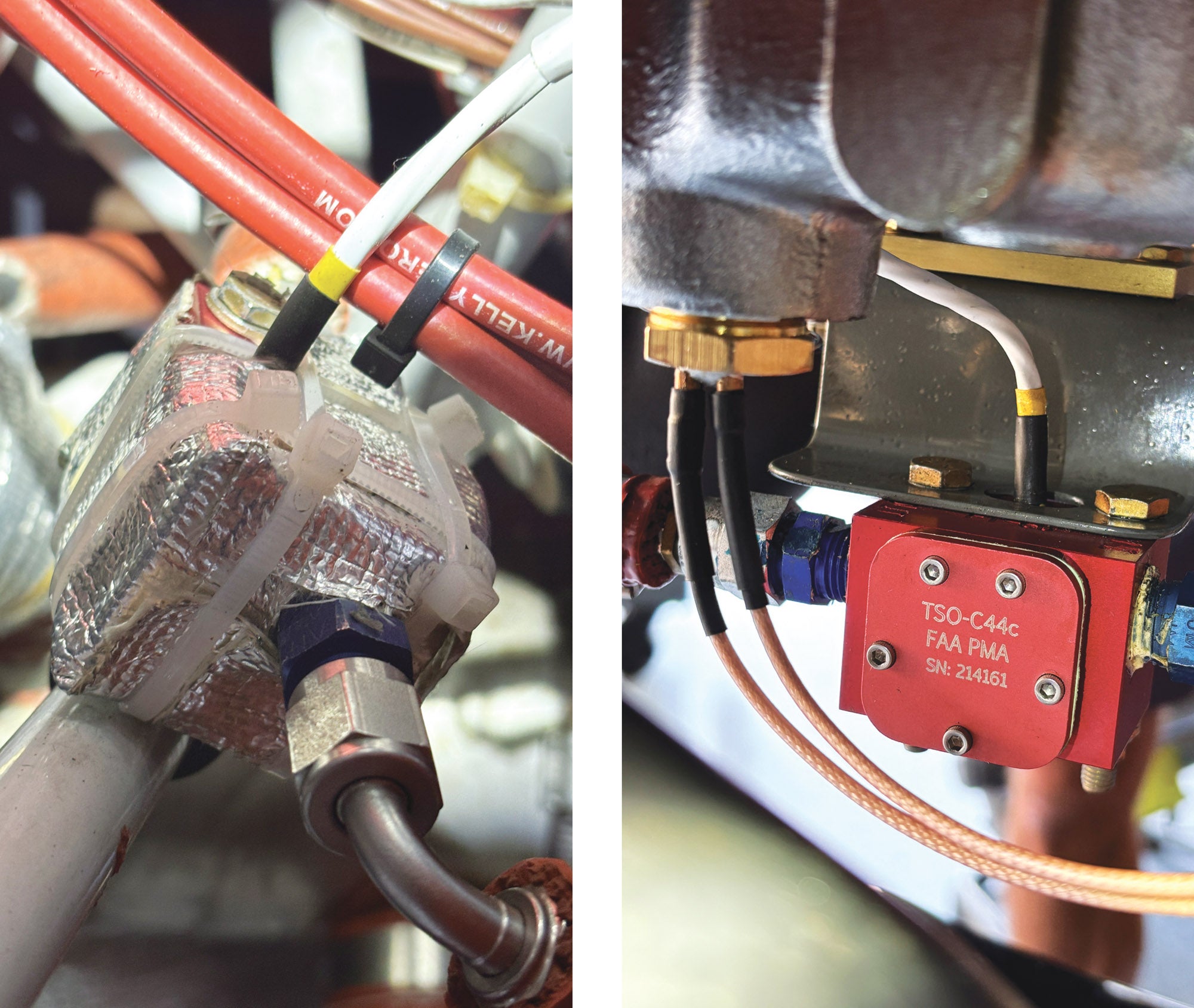

There’s another abnormal indication that can confuse pilots, and it has to do with fuel flow. With today’s glass cockpits, the fuel flow is sensed by a unit that is placed directly in the fuel line going to the engine. Knowing where it is placed within your aircraft can help in understanding a potential problem when indications are outside the normal operational parameters.

Most of the failures I have seen usually have the fuel flow indicating zero because the unit fails or something lodges in the sending unit. The fuel pressure gauge is a good cross-check for this one, but the best indication usually comes from your ears. If the engine continues to run normally, it’s probably an indication problem.

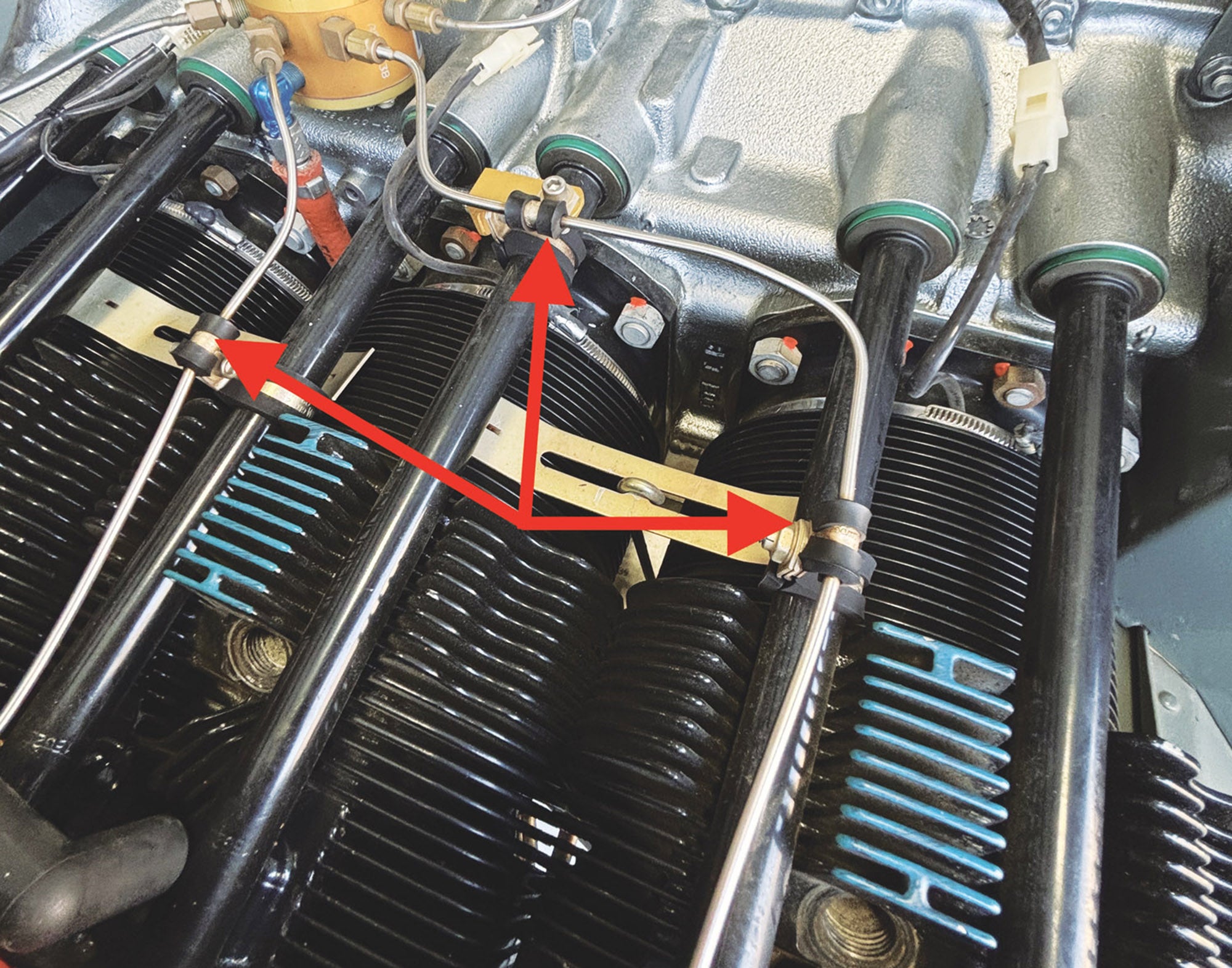

An abnormally high fuel flow indication is something that needs immediate attention but not necessarily a course of action until it is confirmed. It could very well be indicating that there is a fuel leak downstream of the sender, especially if the engine continues to run normally. A rough-running engine, coupled with high fuel flow, could indicate a broken injector line if the sending unit is between the fuel servo and the fuel distribution unit. This could be a very serious engine fire issue and needs to be dealt with immediately.

You can confirm this scenario if you have a multi-cylinder EGT/CHT gauge, as the affected cylinder should show a huge, rapid decrease in EGT and a decreasing CHT, although not quite as rapid. It is important to reduce power and set a course for a landing spot. Reducing power will reduce the pressure in the fuel lines to the cylinders, hopefully decreasing the fuel spray from the broken injector line.

A steady, high fuel flow reading coming from a fuel flow sending unit that is plumbed before the fuel servo or pump could be a leak in the downstream plumbing. Fuel leaks in the engine compartment are not to be treated lightly. The airstream will fan the flames and even act like a cutting torch if the source is not turned off.

It’s very easy to get complacent in our nice, new airplanes with all the shiny gadgets. Most of them are very reliable, but occasionally, a gremlin wakes up and tests us. I think it’s important to be prepared for those scenarios. Personally, I spend a lot of time thinking about various potential situations while drumming along in cruise flight with the autopilot. It keeps the fun factor alive for me.