After 20 years the long-gestating DeltaHawk diesel is suddenly hotter than Jeff LaVelle’s turbos on a 400-mph lap. We knew this last year, but the incipient feeding frenzy circling the DeltaHawk booth at AirVenture last July just about had us reaching for that knife we strap around our ankle. Certainly the world seems ready for something new in aircraft piston engines: something with no valve train to stick, something compact, something powerful burning Jet A, something efficient and not electronically intensive. The DeltaHawk, not yet in production but already certified in 180-hp tune and currently working on 200- and 235-hp versions, punches all those tickets. No wonder the early adopters were looking for any morsel to feed their interest.

DeltaHawk helped the AirVentureteers along with an RV-14 under construction and sporting one of the direct-drive, two-stroke, inverted V-4s on the nose. The installation was in mid-fulfillment, with a cowling-and-spinner combo that apparently was there more to suggest a cowling is coming rather than being the definitive prototype. Nevertheless, the general proportions of the powerplant were on clear display. Owned by Craig Saxton of Oregon, the RV-14 hits the center of DeltaHawk’s core Experimental market, as does the next RV scheduled to get the firewall-forward treatment, the RV-10. For now Saxton’s -14 is plowing fresh ground in developing an engine mount accommodating the DeltaHawk’s bed-style mounting to a Lycoming dynafocal world. Eager and well funded, we expect Saxton’s RV-14 to come together soon enough.

Also look for Piper Seminole twins wearing a brace of DeltaHawk DHK180s, as an STC for the popular multi-engine trainer has already been obtained and the training market is eager for a non-gasoline platform. Four-seat Bearhawks are another airframe of DeltaHawk’s interest. This is not to forget DeltaHawk already has several engines in test flight, including in a Velocity and a Cirrus SR20.

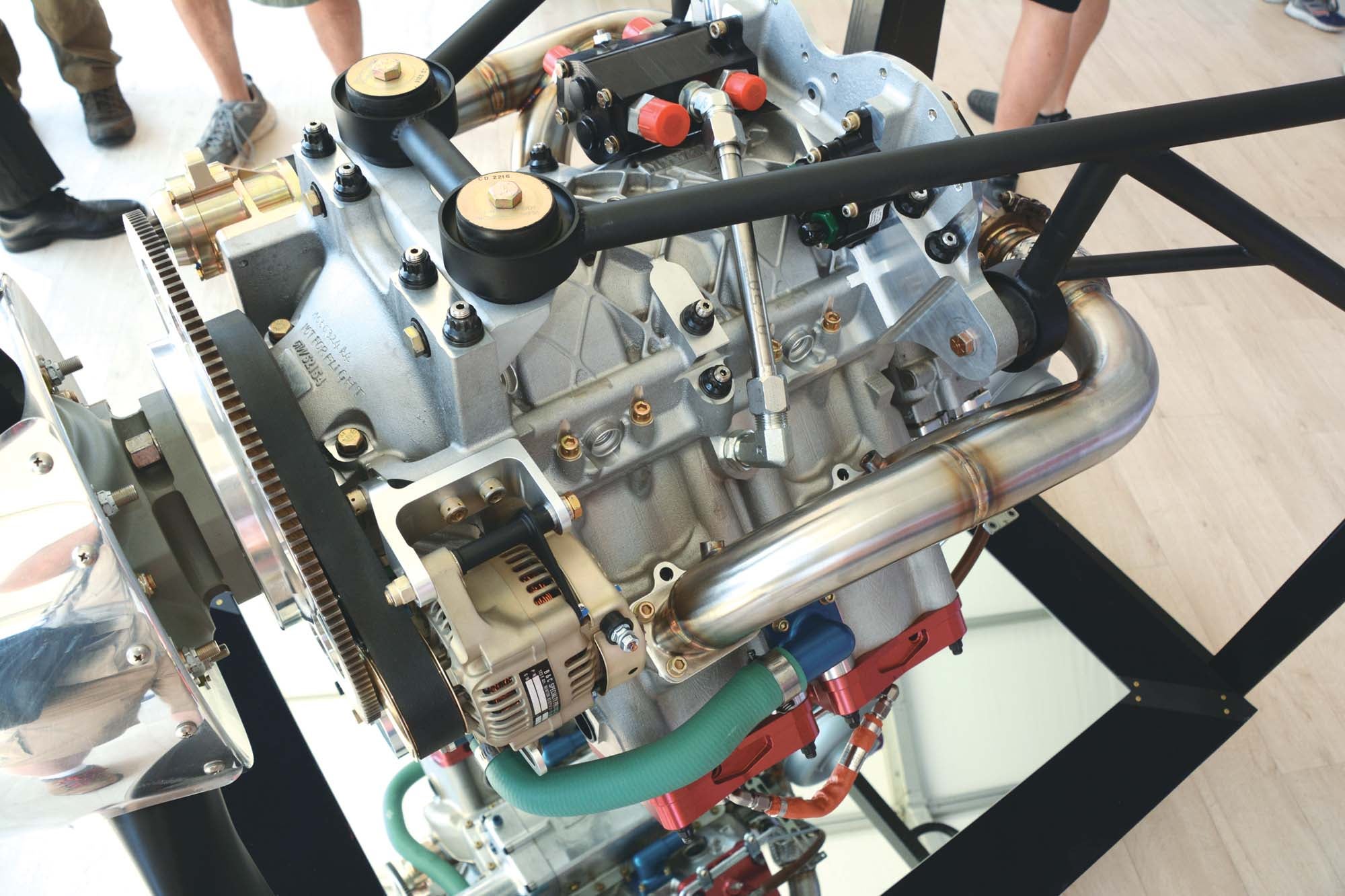

At AirVenture they also had some hardware changes to tout. The main bearing girdle, or engine plate as it is sometimes called, has been redesigned to save weight. Once a primitive, rounded slab of aluminum, the plate now carries extensive ribbing, which is modern engine practice. Some external hoses have been incorporated internally as oil passages in the revised timing cover and the flywheel has been lightened. All are welcome changes and weight could be down as much as 15 pounds.

Perhaps a little harder to take is the announced price of $110,000 for the 180-hp engine. Now, before you pop your Vernatherm, that is for the engine and firewall-forward kit, so it includes the cowling, engine mount and all accessories, save the charge coolers (intercoolers). The precise firewall-forward hardware lineup was not finalized at our deadline, but even at six figures the price seems in the ballpark for an all-new, purpose-designed aircraft engine with nearly all the trimmings, not to mention a possible 35% increase in fuel economy (better fly a lot to realize that cost savings). No pricing is available for the 200- and 235-hp variants as they’re still in development, but expect small increases as the 200-hp engine needs only fuel delivery tweaks and the 235-hp version gets those same fuel adjustments along with a larger turbocharger. Incremental changes in other words.

Realizing DeltaHawk’s Racine, Wisconsin, headquarters was on our way home (thanks to commercial flights ascending vigorously out of the intensely intercity Chicago Midway), we were fortunate enough to rapidly tour DeltaHawk’s facilities as part of our AirVenture walkabout. And let me pause here to acknowledge everyone at Delta-Hawk has been refreshingly supportive and transparent with information, tours and firm handshakes. It’s an encouraging sign surrounding their project.

Seeing Is Believing

In bucolic Racine we were met with an impressively fresh, technologically intensive facility along with Test Technician Manager Connor Naeve to see us through the two major buildings. The first houses the business and engineering offices (overly ample room for the current 53 employees) in front and the prototyping and production shop in back. The second building is a test facility offering two state-of-the-art propeller dynos, one water brake dyno and a motoring stand where a non-running engine can be driven by an electric motor. Various fuel system and supercharger test rigs were also in evidence, plus we were able to eyeball a good number of internal engine parts and made a pass through one of the dyno data rooms while a test engine was fanning the local atmosphere.

One unavoidable observation was the production/assembly area of the factory was empty floor space devoid of workstations. DeltaHawk’s CEO, Christopher Ruud, later explained, “Our business model is to outsource all the component manufacturing, but we own the design and tooling. We utilize our facility for quality, assembly, test and distribution…the back-end system is built and able to be audited, and the only thing missing are the assembly workbenches that we will order in quantity when we receive our production certificate.”

This illustrates the next high wire to navigate during the major transition from hand-built prototypes to volume demand. DeltaHawk has taken the commendably long view so far, and we suspect patience will continue to be a virtue in the turn to production. Of course the Department of Defense or a busy airframer could kick-start the process via an order for drone or other engines, so we’ll see how it goes.

We were reassured by the quality and right sizing of the development equipment. The prototype department was well equipped to bend, weld, drill and cut metal without having been turned into a gadget freak’s money pit. Likewise the dyno facilities were first rate, showing intelligent purchasing discipline, which is not to say they are sparse—far from it. The slatted anechoic panels were especially notable in their ability to hush the continuous engine running. And for lab fans, an abundant supply of stands, hoses, filters, pumps, data acquisition, cameras, precision measuring equipment, monitors, stainless plumbing and all the other glitterati of a serious development center was much evident. You couldn’t toss a stuck exhaust valve without hitting something interesting.

Perhaps the most impressive find was the Paul Bunyan dimensions of the engine internals. Something of a professional tour-taker, I’ve been intimate with the entrails of piston engines ranging from Cox Thimble-Drome screamers to Top Fuel dragsters and 43,200-hp ship engines with man doors on the crankcase. And certainly the DeltaHawk internals are the sequoias of small plane engines. My admittedly semi-educated observation is the design exceeds beefy and delves into the realm of “they can’t possibly break this” engineering. The crankshaft is remarkably short with massive bearing journals, the steel pistons could be two-handed ceremonial Oktoberfest beer steins and I’ve seen pistons smaller in diameter than a DeltaHawk piston pin. The titanium connecting rods offer generous bearing area and are quite long while the block is castle-like and houses cylinder liners thick as an adolescent. Clearly this engine is designed to run at eye-watering cylinder pressures for a long time.

One quirk is four pendulum dampers on the crankshaft counterweights (probably due to the V-4’s odd fire characteristic). But that’s getting ahead of ourselves; watching DeltaHawk’s maneuvering to full production is the next big step for this promising company’s path to bringing a new generation of power to general aviation. It’s looking good so far.

Given that the Delta Hawk is a 2-stroke, what are the odd firing characteristics ?

This immediately caught my attention as well. 90 degree two stroke V-4’s have an even firing order of one power pulse every 90 degrees of crank rotation. Further, given that the top of the exhaust ports are more than half way down the stroke, the propeller always realizes positive torque from the engine.