Back when we lived in Texas, we took a trip to visit family in Minnesota from our base near Houston. Louise had taken the RV-6 to Pensacola recently, so it was the RV-8’s turn for a cross-country trip. Besides, Louise hadn’t flown the Val for a number of months and wanted to get current again, so we filled it up and got ready to depart at dawn on a Thursday. We planned the normal two-hop trip with a fuel stop in the Kansas City area.

The weather looked, well, interesting. As usual. We had been watching the seven-day forecast charts for several days and the predictions were for an area of significant thundershowers across Iowa. It looked good to the west, however, and it was clear south of KC, so the strategy was to take up a direct heading to one of the airports on the east side of that metro area but to reevaluate about Joplin to see if a deviation west made sense. Because I have more experience with the avionics in the bird, I had my better half fly the first (longest) leg out of Houston while I “rested my eyes” in the back seat for the first few hours. This would leave me fresh and rested for the interesting part of the trip.

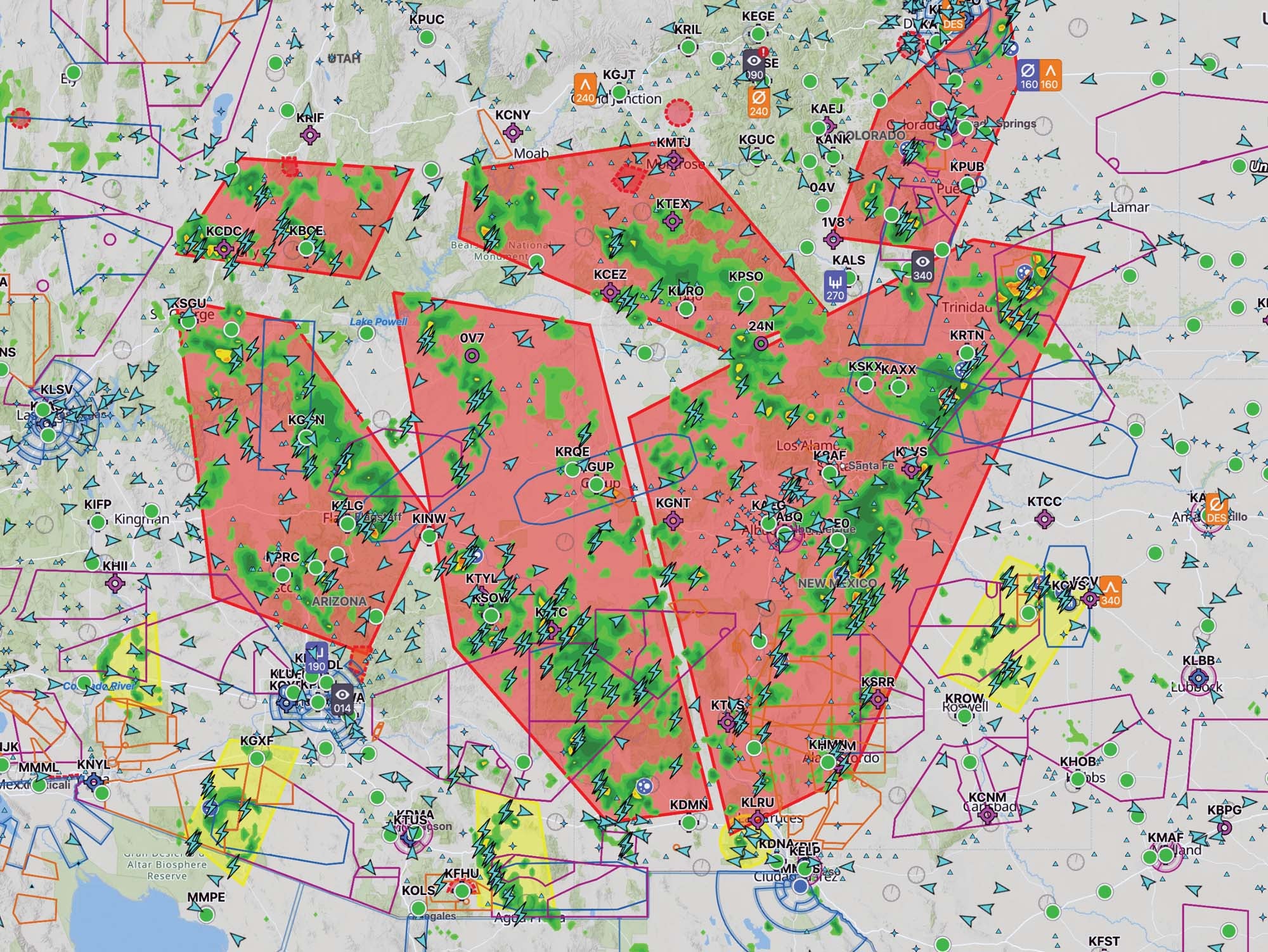

I have a vague recollection of haze over the Ouachita Mountains, but I didn’t actually start to take interest in the weather up ahead until about the time we crossed into Missouri. We both had access to onboard weather, allowing us to compare notes. It became apparent from a first glance that the area of thunderstorms was going to be much bigger than Iowa, with a fairly solid mass covering that state and extending east, plus scattered areas of red and yellow echoes in broken blobs going east across Kansas and north into Nebraska.

The whole air mass was moving northeast, but not very quickly—and there were wide lanes without any echoes at all. METARs were almost all VFR—even where it appeared there were showers. I figured that the storms were popping up, dissipating and moving around more quickly than the hourly reports could keep up. It became apparent as we tracked north through western Missouri that the way around the east side of KC and then north was closing up. If we were going to get through, it was going to require a westerly track—assuming we could find one. Fortunately, there are lots and lots of airports in the Great Plains—and an equally large variety of hotels in which to spend a night.

The First Stop

We elected to drop in to Butler, Missouri, about the time we got there, so Louise spiraled down and made a nice landing before we taxied in to top off the fuel and review weather strategy. I didn’t really want to file IFR and get up in clouds with embedded thunderstorms, so the plan was to stay VFR and go low, remaining above the minimum safe altitudes while keeping an eye on the NEXRAD to find a reasonable route. We would always keep a clear path of retreat to an acceptable airport, and if we had to go below the MSA or visibility dropped such that we were worried about staying VFR, that would be time to abort and set down.

Both of us would scan the weather with our respective units and while I would plan a route, Louise would keep track of the retreat options. We would both bounce our plans off the other to make sure we were in agreement—after all, we were both in the same airplane! Reviewing these “rules of engagement” before takeoff made sure that we were both on the same page and reinforced the fact that we would work together to stay safe. Getting to our destination was secondary, and we actually had at least an extra day to get there if we needed it.

Taking off out of Butler, I set a course using the autopilot and EFIS to take us just south of the two Olathe Class D airports, then turned more northerly toward Lawrence. The weather was fine up to that point, so we next pointed at the Pawnee VOR but noted some low clouds up ahead. They coincided with some green precip on the NEXRAD, with dissipating yellow and green in some cells to the west. North of our course, the dissipation was obvious from looking at the animate mode. This was good news, but we still had a few scattered lower clouds to deal with—the moist remnants of the thundershowers that had moved through. The visibility and ceilings started to drop as we headed northwest, and it started to look far better due north, so I picked up a highway headed that way. This was nice because it had a town with an airport about every 20 miles or so—great places to go if we ever got scared.

We picked our way northbound from town to town, flying at the MSA shown on the VFR charts, and the sky above lightened quickly. Looking at the onboard weather depiction, it was obvious that we had moved north of a cold front that wasn’t even supposed to be there (according to the forecasts) but had clearly gotten delusions of grandeur. With that behind us, the winds had shifted to be more out of the east and we motored along with a building tailwind—next stop, a slot about 50 miles wide to the east of Omaha. My first thought had been to go around the west side of the city, but a new pulse of atmospheric rage suggested that if we tried that route, we’d be overnighting in Rapid City before we knew it. As planned, Louise and I discussed each option as they came and went and were never far from a good runway—with her tracking the necessary frequencies should it be time to go in for a landing.

Adding Assets

The terrain (flat) was a great asset in that we didn’t have to worry about rapidly changing MSAs as we flew along our course. Leaving the path of the Missouri river behind, we saw a few hills at the edge of the floodplain, but beyond that there was nothing to worry about but towers—and the MSA kept us above those. The masses of thunderstorms shown on the NEXRAD were easy to see out the canopy—down below the bases, the visibility was pretty good, as is often the case. Seeing the exact current conditions ahead, rather than what might be a delayed picture on the XM weather, is invaluable. If we had been IFR, up in the clouds, we would have had little to no warning if the storms had changed rapidly and the onboard weather depiction had fallen behind.

Operating as a crew, Louise and I kept conversing about what we saw on the radar and what we saw out the windows, always keeping a clear path to a good airport in our hip pocket. Before we knew it, we had slid through a 30-mile side gap that signaled the last stormy area and had a clean shot to the Twin Cities from just east of Fort Dodge, Iowa. The winds had been interesting to watch along the way. South of the storm area, we had tailwinds all the way from the Gulf. Within the storm band, the winds were mostly from the east, giving us a right cross with a little bit of tailwind component down low, yet they sheared back to a tailwind above about 5000 feet. Once we cleared the storm band, we had headwinds down low and tailwinds once again at 5000 and above.

This turned out to be a fascinating trip from several perspectives. The weather was interesting and the route-finding challenging. It proved once again that a deviation of even 100 or more miles is a fairly nonevent in a fast, long-legged RV. And it showed how comfortable having a reliable and well-trained partner can be in helping to evaluate not only a course of action—but the decision-making process that goes into that plan.