After years of doing first flights and post-maintenance flights, as well as hearing about failures from our customers, I thought I would share some of the more common ones along with some recommended courses of action. Some failures in flight can just be annoyances, like a USB outlet failure or a stuck vent, but some of them might require action to prevent a more serious situation from occurring. Those are the ones I want to focus on, and it may take a couple of columns to cover them.

For those of you who are flying your own airplane regularly, it is easy to get complacent. After all, everything worked fine last time. Every time I get in the cockpit, my practice is to brief myself on what course of action I will take if some event occurs during the takeoff roll. Takeoffs are certainly the most critical part of the flight, and it is best to be mentally prepared prior to the throttle moving forward.

Canopy/Door Warning

The most common mistake, especially during the hot summer months, is that a door or canopy is left unlatched. Yes, many of us put warning lights on them, but from experience I can tell you that it is easy to forget about a warning light that is constantly on. This is especially true when there is a distraction such as the tower telling you that you are “cleared for an immediate takeoff without delay, traffic on 3-mile final.” To help with this, I installed a microswitch in the throttle quadrant that only arms the door warning lights when the throttle is advanced.

So, when the door warning light illuminates during the takeoff roll, there is only one proper course of action and that is to abort the takeoff. Announce your intentions when you have the aircraft under control. If the door or canopy pops open after you have left the ground, only abort if you have enough runway remaining. Fly the airplane and do not get distracted trying to close the door. One RV-10 crashed, killing the solo pilot, when the passenger door popped open on departure. Fly the airplane. I can’t say that enough times. Slow down if able.

For RV aircraft with tip-up canopies, the canopy will pop open a few inches, but the aircraft should remain controllable. More than a few RV-10 doors have departed the aircraft, albeit with some damage to the tail, but the planes were still flyable. I had a local friend completely lose his RV-4 tip-up canopy and the aircraft was still controllable, although it was quite windy in the cockpit!

Propeller/Engine Overspeed

During initial flight testing, until the propeller governor and low-pitch blade stops are correctly set, it is possible to get an engine/propeller overspeed warning on climb-out. The wrong course of action is to reduce power with the throttle. Yes, I know everyone was taught to first reduce the throttle, then the prop. That’s for a correctly adjusted governor. In this case, you could end up reducing the throttle so much that you will adversely affect the ability of the aircraft to climb. The proper course of action is to slowly reduce rpm using the prop lever.

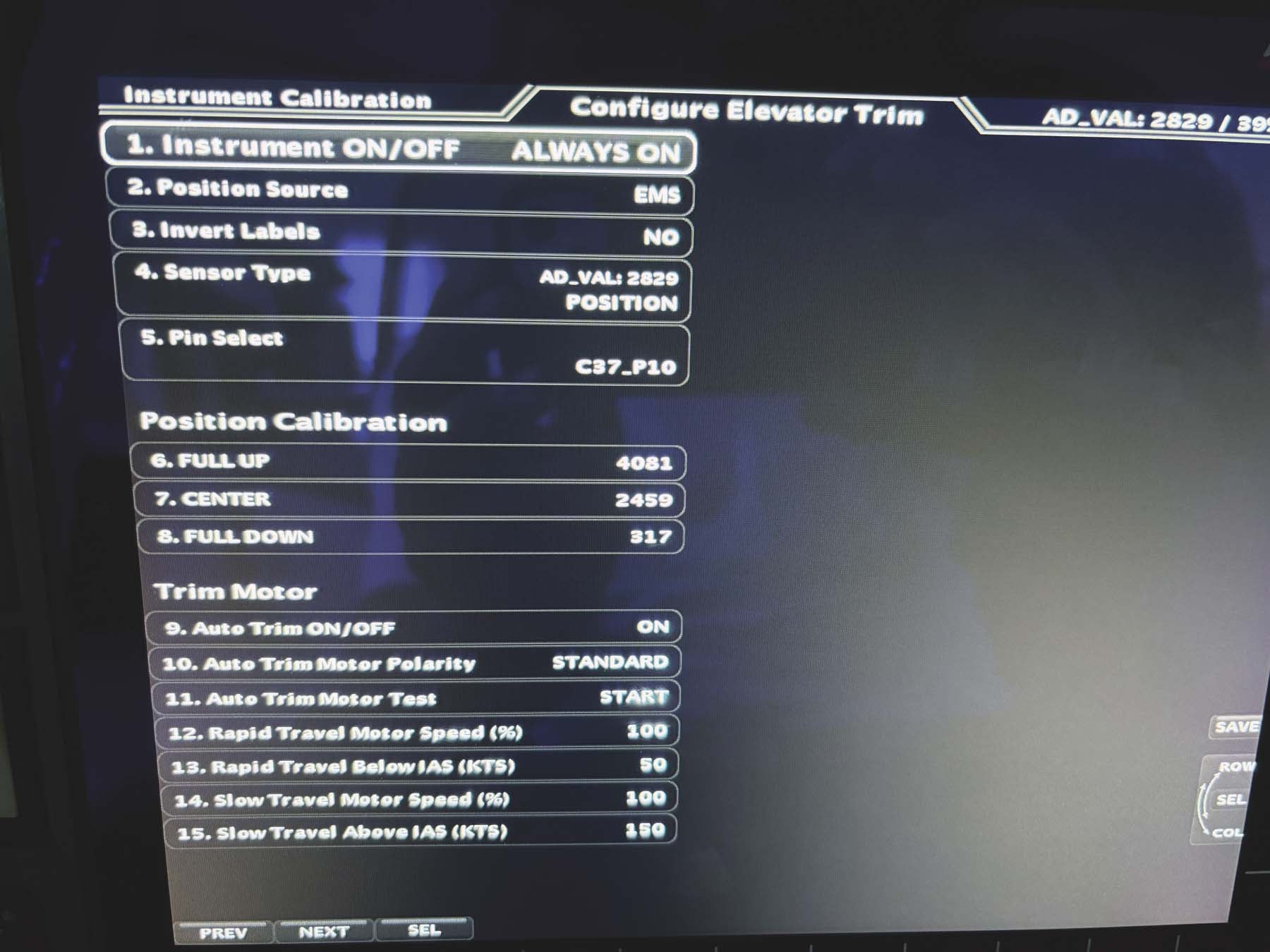

Inoperative Trim

Once the climb is completed and level-off begins, the aircraft accelerates. Too many times I have seen the pitch trim become inoperative. In some of the RV aircraft, the stick forces required to maintain level flight can get quite high. The proper course of action in this situation is to reduce the power (with the throttle). Remember, the trim is only good for one airspeed, and if it felt good during the climb, then slow to that airspeed. If two pilots are on board, and you are VFR, you might be able to troubleshoot the problem. It could be a circuit breaker or fuse, but often I have found it to be a configuration problem.

Many EFISes and autopilots now allow us to adjust the trim motor speeds for different phases of flight, but they don’t always get set properly on new aircraft. It’s best to land and sort it out on the ground. Keep the speed slow enough to keep the stick forces manageable but pay attention to your airspeed and get ready for higher stick forces on final and in the flare. Consider diverting to an airport with a longer runway if you are uncomfortable. The airplane will fly slower all day long. Just don’t get distracted by potentially higher CHTs and oil temps due to the slower cooling airflow.

Alternator Overvoltage

There is one electrical failure that requires immediate action, and that is an overvoltage warning. I’ve seen a few panels damaged ($$$) by pilots not taking immediate action when this occurs. The immediate response should be to turn off the alternator. Yes, I know that avionics today are usually good with voltage between 10–30 volts DC, and an overvoltage warning of 18 volts might not seem like a problem. But not everything can take 18 volts, such as the battery. It will get cooked. It could cause a fire. Once it fails it will no longer absorb the high voltage from the alternator, which could spike even higher now, potentially taking out the avionics. This is not a good situation.

If turning off the alternator does not fix the problem, you need to consider pulling the alternator circuit breaker, if you have one. This should be a big 40- or 60-amp breaker, not just the 5-amp field breaker. If that still doesn’t work, your next step is to turn off the master switch. You have tested this on the ground, right?

During preflight, if you have glass panels and electronic ignition systems, it’s important to make sure your primary screens work on the backup battery and the engine will remain running.

Next issue I will continue with a list of other common failures and the proper courses of action to keep the fun factor alive. I welcome feedback from any of you who may have stories to share so that others can learn!

During an alternator overvoltage condition , if installed, the overvoltage module will shutdown the alternator, at a voltage of more than 16 volts.

However, in Piper aircraft , with a Chrysler trype alternator, the field wire is grounded by the voltage regulator So, a short in the field wire will cause the alternator to go the full output, and the field breaker will have no affect.!

The main alternator breaker must be pulled and will disconnect the alternator from the buss.

In Cessnas and others that use a Ford type alternator, the regulator supplies 12 volts, or less, to the field. So, a short in the field wire will trip the field breaker. That will usually shut down the alternator.

Turning off the master and disconnecting the battery may not disable the alternator; some will supply their own field voltage through the regulator.

Another thing that a pilot can do is to reduced the power to near idle.

Most alternators are able to barely output 14 volts at idle. This will give the pilot time to do the other things to try to resolve an overvoltage condition.

Well maybe. Usually they do OK on a charged battery, which is usually the case after being in cruise flight for a while. There may not be the option to go to idle if IMC.

I agree, maybe;

If the battery is fairly new. An older battery will have lower A-H capacity.

It also depends on the voltage regulator setting. I’ve worked on aircraft where the V-reg was set to 13.3 volts, and the alternator never fully recharged the battery.

So, maybe the aircraft will have 30 minutes of battery. Less if at night.

And a pfd and mfd have backup batteries. But how new are those ?