There isn’t a pilot alive who doesn’t know what a checklist is. There are, however, pilots no longer with us who failed to use one.

A cockpit is a busy place. Consciously and subconsciously, pilots process thousands of bits of information each second to maintain situational awareness and control of the airplane and monitor the health and status of the airplane’s systems. Checklists help pilots remember the important bits at the important times. There are checklists for preflight, pre-start, start-up, pre-takeoff, takeoff, landing, shutdown, emergencies and vomit in the cockpit. (I’m seeing if you’re paying attention.)

Checklists help pilots remember the things they need to remember at the time, and in the order, they need to remember those things. Conversely, checklists let pilots forget things when those things aren’t important. For instance, the landing checklist relieves you from having to think about the landing gear while in cruise. (“Wilder, help me remember to put the gear down before we land, OK?”) That frees your mind to wonder why you included “MacArthur Park” in your Flying Songs playlist and ponder why Elvis never covered it beyond a few playfully mocked lines while taping his 1968 TV special. (Ah, the price Building Time readers pay for my 1300-word budget.)

The Experimental/Amateur-Built Aircraft Checklist

Pilots of Experimental/Amateur-Built aircraft are often new to the aircraft (flight schools and flying clubs with E/A-B aircraft are as hard to find as a witness in a mob hit) and the specific aircraft they fly is not only unique in the world, it is often new to flight. Further, it is common in homebuilding for a builder/pilot to come back to flying after an extended period of flight dormancy. Their time, money and attention were focused on a years-long homebuilding project, which left them unpracticed in cockpit management and unpolished in the nuances of flight. A new, one-of-a-kind airplane paired with a rusty pilot is a dangerous combination. That gives us experimenters even more reason to use a checklist than the average PIC.

There are about 2600 copies of Van’s RV-6 flying. I challenge you to find two that can share a checklist (or weight and balance spreadsheet) without edits. It’s safe to say that all of them need the fuel turned on for the engine to start—however, it’s in the details that one lives or dies. A quick think on my years at Sonex recalls customer accidents that would have been prevented had a checklist been followed.

The first to mind, one repeated too many times, is the failure to close and lock the canopy. Some pilots lost their lives to this oversight. Think about that, and then think about that some more. Others found themselves at low altitude, headsets stripped from their heads, disoriented by the violent introduction of loud, turbulent wind to the cockpit, fighting an unfamiliar drag profile to get safely down. What’s more, while all Sonex aircraft have one canopy latch that needs to be locked, some builder modifications require two latches be locked. Without an airplane-specific checklist—and without using the airplane-specific checklist—a Sonex pilot used to one canopy latch can find themselves in peril flying a Sonex with the nonstandard two latches.

No Checklist Entry Is Insignificant

Have you ever encountered a dead battery because a master switch was left on? Maybe it was in a rental aircraft or a friend’s airplane. (I’m sure you never did it.) It’s not that the pilot forgot to turn the switch off, it’s that they failed to use the checklist, which reminds them to turn the master switch off. Shutdown seems so innocuous. What can go wrong if a shutdown checklist item is missed? I can think of one thing. When the master is left on, the starter switch is often one bump away from enlivening the prop and striking a person. I’ve seen it. (Thankfully the starter button was independent of the ignition switches.) I cringe, especially at fly-ins, when someone is in a cockpit while another person is nosing around the prop.

Airplane checklists save lives and prevent injury. If there was no danger in operating an airplane there would be no need for checklists. Forget to move the mixture full rich before landing? Pffft. How can that matter? You’ll find out if you have to go around and the engine can’t develop full power because the mixture is too lean. Controls free and clear? Ooof. The takeoff roll is not the time to discover a gust lock wasn’t removed. Mag check? Finding an ignition problem before taking flight is better than finding out in flight, unless you’d ignore the issue and fly anyway, as one pilot did, because he had a second ignition. He had a second seat as well, which meant he could carry a victim. A disciplined pilot will not only use a checklist, they will use it as that little voice that says, “Something isn’t right, take it back to the barn.”

A First Flight Checklist

The importance of that little voice on a first flight cannot be overstated. First flights come with pressure and, often, an audience. The pressure to go is great. The discipline to not is necessary. To temper the stress inherent in the first flight of my unproven airplane, I created an expanded first flight checklist. It was my hedge against an oversight during a flight that could end my life or muck up five years of work. The expanded checklist also served as a detailed first flight profile. I twitch at stories of unintended first flights which, even when successful, always result in an unprepared pilot improvising a first flight on the fly. Literally.

From the comfort and (relative) safety of my sofa (we had cats), I penned the checklists for my first flight. I threw everything I could think of in them so I wouldn’t have to think of those things later. Then I let them sit and thought some more. Quiet time to think was a luxury I wouldn’t have in the air, though the cockpit would benefit from being cat-free. I sat in my cockpit and exercised my draft checklists looking for gaps, overlaps and items out of sequence. My hands moved about the controls as dictated by the checklist. By the time I perfected my checklists I knew my cockpit from an operational standpoint, not just a builder’s standpoint. Repeatedly running the checklists in the cockpit also served to build muscle memory, the automatic movement of a hand or finger to a precise place. If I could find the trim lever without looking I was less likely to porpoise while making trim adjustments. If I could find the flap handle by memory, I could incrementally deploy and retract flaps without taking my eyes off the airspeed indicator and horizon. To quote a friend, “All good stuff.”

“MacArthur Park” wasn’t on my Flying Songs playlist; however, “Danger Zone” was. “Metal under tension….” My first flight checklists served to keep the tension mostly in the metal and out of the cockpit. It also kept the distractions of music and video equipment out of the cockpit for the first flights. It’s impossible to know how the first flight would have gone without such preparation, but I’m still here to tell you that, beyond the threat of a paper cut, using checklists does no harm. If you wish to fly in a manner that permits you and the airplane to fly again, checklists are critical to that goal.

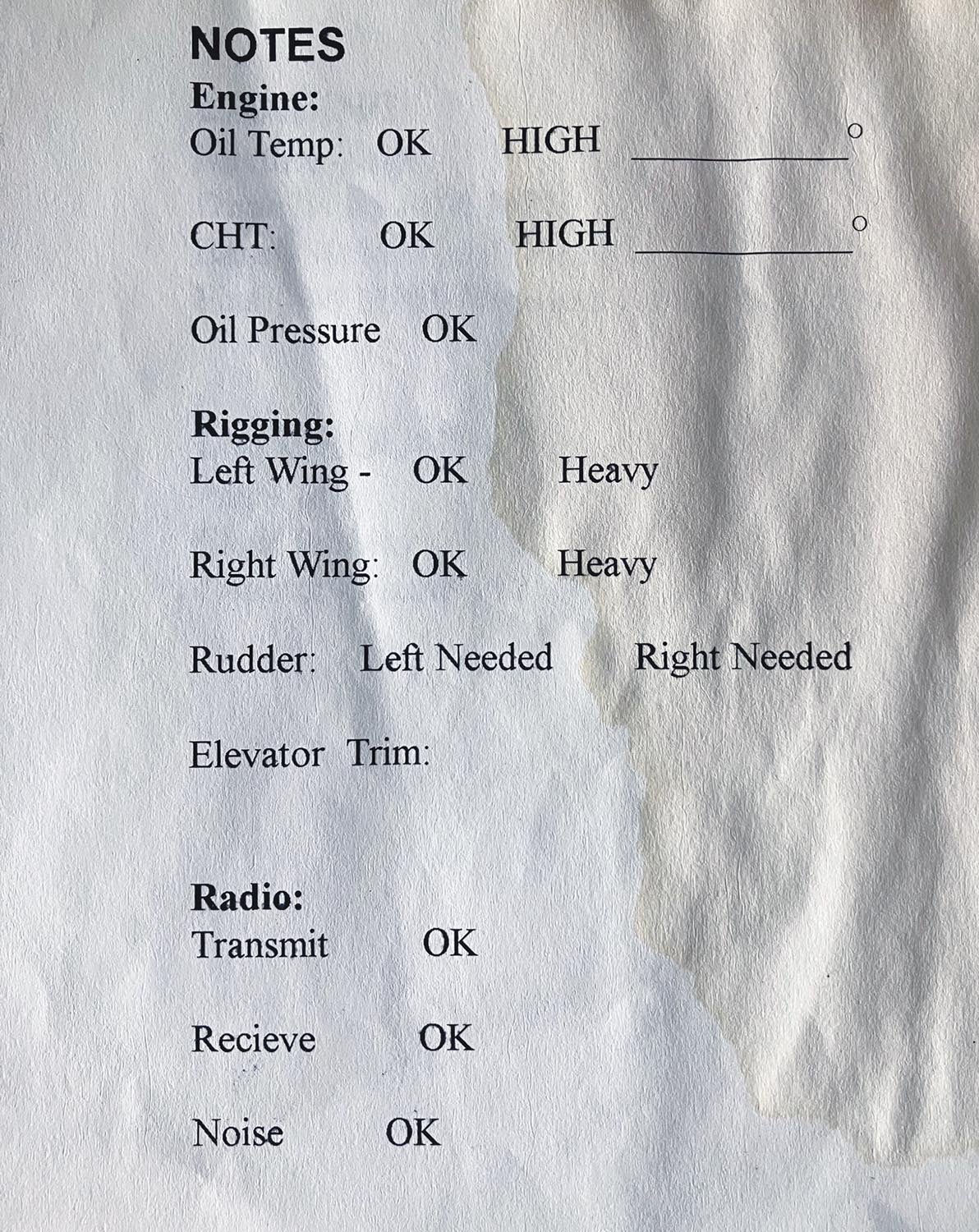

Having “OK” on the checklist is a good visual reminder that you haven’t skipped an item.

That is a very good point, Susan. Thank you for reading and commenting.

~Kerry