In today’s aviation world of quickbuild kits, match-hole-riveted parts and fast glass, it’s easy to forget how things were not so long ago. Back when everything had to be made by hand from blueprints without the benefit of the machinery and technology we currently enjoy. Yet, there is a sense of beauty and joy when you see aircraft created through such time-consuming and painstaking efforts come to life! Even more beautiful and enjoyable is seeing these handcrafted machines continue to fly decades later.

In today’s aviation world of quickbuild kits, match-hole-riveted parts and fast glass, it’s easy to forget how things were not so long ago. Back when everything had to be made by hand from blueprints without the benefit of the machinery and technology we currently enjoy. Yet, there is a sense of beauty and joy when you see aircraft created through such time-consuming and painstaking efforts come to life! Even more beautiful and enjoyable is seeing these handcrafted machines continue to fly decades later.

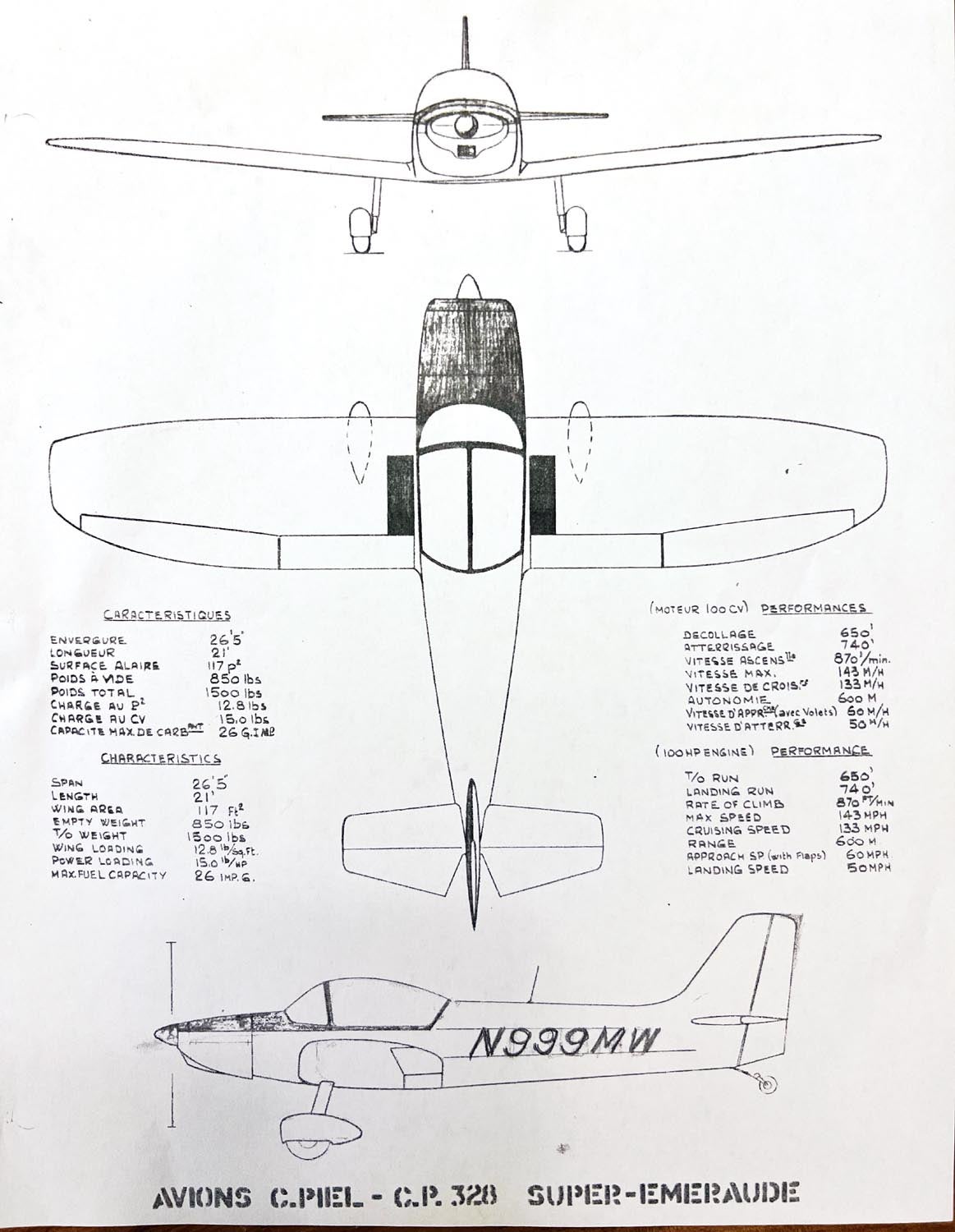

A bit of the history of this beautiful airplane design starts with Claude Piel. He was a French aircraft designer who created his first design in 1943 at the young age of 23. It was a variation of the Flying Flea and the design was ultimately abandoned. However, it provided practical knowledge to pursue further designs. His second aircraft, the single-place, low-wing CP.20 Pinocchio, resembled a miniature Supermarine Spitfire and became the basis for the CP.30 Emeraude (Emerald) in 1953. First unveiled at Toussus-le-Noble, it was powered by a 65-hp engine. When it was refitted with a 90-hp Continental it became the fastest civilian two-place aircraft designed in France at the time.

The Emeraude was a clean design with sensitive and balanced controls and found a ready home with French flying clubs and private owners. The design progressed with larger engines, a swept tail, a sliding canopy (instead of upward-opening window/doors) and strengthening of the airframe to become the Super Emeraude. Claude Piel’s partnership with Auguste Mudry at CAARP (Cooperatives des Ateliers Aéronautiques de la Région Parisienne) eventually lead to the development of the very successful and well-known CAP 10 aerobatic monoplane, which uses the same wing with a NACA 23012 airfoil.

More Jewels

The Emeraude was followed by the CP.60 Diamant (Diamond) and the CP.750 Beryl (the translation can be simply a “gem,” or it may refer to a gemstone group that includes emerald, aquamarine and morganite, to name a few). Rounding out the series was the single-seat racer, the CP.80 Sapphire (later changed to the Zephir). Claude Piel’s aircraft engineering was a reflection of the French philosophy that an amateur builder would have complete freedom in designing and building an airplane if he wants to successfully contribute to progress in aviation.

The evolution of the Emerald to the CP.328 Super Emeraude involved the above changes, plus manufactured parts, as the aircraft gained popularity and was licensed for production in several countries. The slotted flaps, Frise-type ailerons, plus wing geometry contribute to a stable aircraft capable of tolerating significant crosswinds and yet remaining highly maneuverable. The elliptical wing shape might look intimidating to build, but it isn’t more difficult than any other tapered wing. Actually, only the outboard portions beyond the flaps are elliptical, while the center section remains straight. This is accomplished by progressively shortening the ribs as one moves toward the tips.

Claude Piel partnered with Gene Littner of Canada in the 1960s to market plans. The plans still bear the French Government Agency approval and are of course in metric.

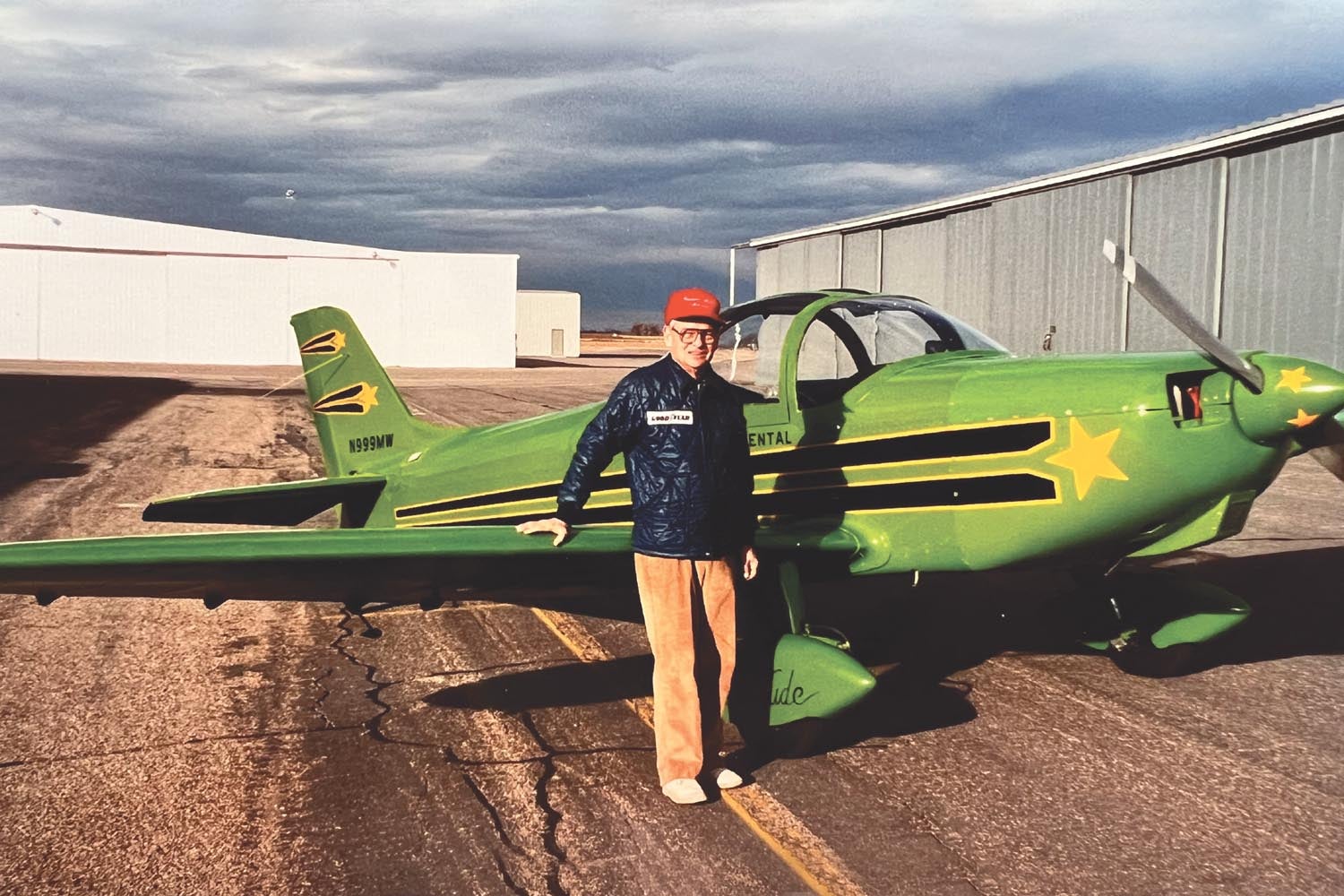

This particular Emeraude was built by Robert Mann, designated an Avion C. Piel CP.328 Super Emeraude, and first flew in 1978 after three and a half years of building. Robert retired from the U.S. Navy after a career as a structural mechanic on T-28s. In the Navy he learned welding and mechanical skills that came in handy when deciding to build his own aircraft. As a master woodworker, he had a second career, teaching students that craft for decades in Colorado and Nebraska.

Before deciding on the Emeraude as a project, Robert exchanged a number of letters with homebuilding legend Tony Bingelis. Reading their correspondences is a trip back to the early days of homebuilt aviation. No internet, no email. Questions, ideas and advice took time for letters to transit through the mail and back. Originally Robert considered a VariViggen, but ultimately decided on sticking with the construction medium with which he was the most familiar, wood. Per Tony, “The airplane is very well designed and efficiently built. Most builders can’t seem to resist the temptation to ‘improve’ it. Can’t be done except to make a change pleasing to your own likes. It is not likely that you can find a lighter way to build any part. Stronger and heavier, yes, but it would only be a waste.” He also recommended using T-88 epoxy throughout, which seems kinda funny these days. Remember, back then T-88 was just coming into widespread use. Tony built several Emeraudes and was a vocal enthusiast of the design.

Construction-wise, most of the building is fairly straightforward; however, the spar can be a challenge. It has both a twist and dihedral and is built as one 27-foot-long piece. The laminated spar caps must be jigged correctly in all dimensions, with those angles and twists, and held in place while the ribs, leading edges, skins and fittings are joined. Once it’s all together it becomes a large cumbersome slab that, while not heavy, requires multiple people to move around.

Over the building years, Robert heeded Tony Bingelis’ advice and stuck mostly to the plans. And, yes, he used T-88 epoxy. Of course, he couldn’t help but add his own touches. A fellow Emeraude builder, Carlton Whiting of San Diego, California, came up with an idea to use the main landing gear from a Piper Cherokee on the Emeraude. This was easier to install and saved on fabrication time and expense. A Cherokee at an airport near where Robert lived was destroyed in a tornado, and he picked up the landing gear and the engine from the wreckage. Later he built a CP.750 Beryl and used the same landing gear setup. With over 3000 incident-free landings on the Beryl, he’d use the same landing gear setup any day. The O-320 from the wrecked Cherokee was overhauled for the princely sum of $2482.30! The good old days, indeed!

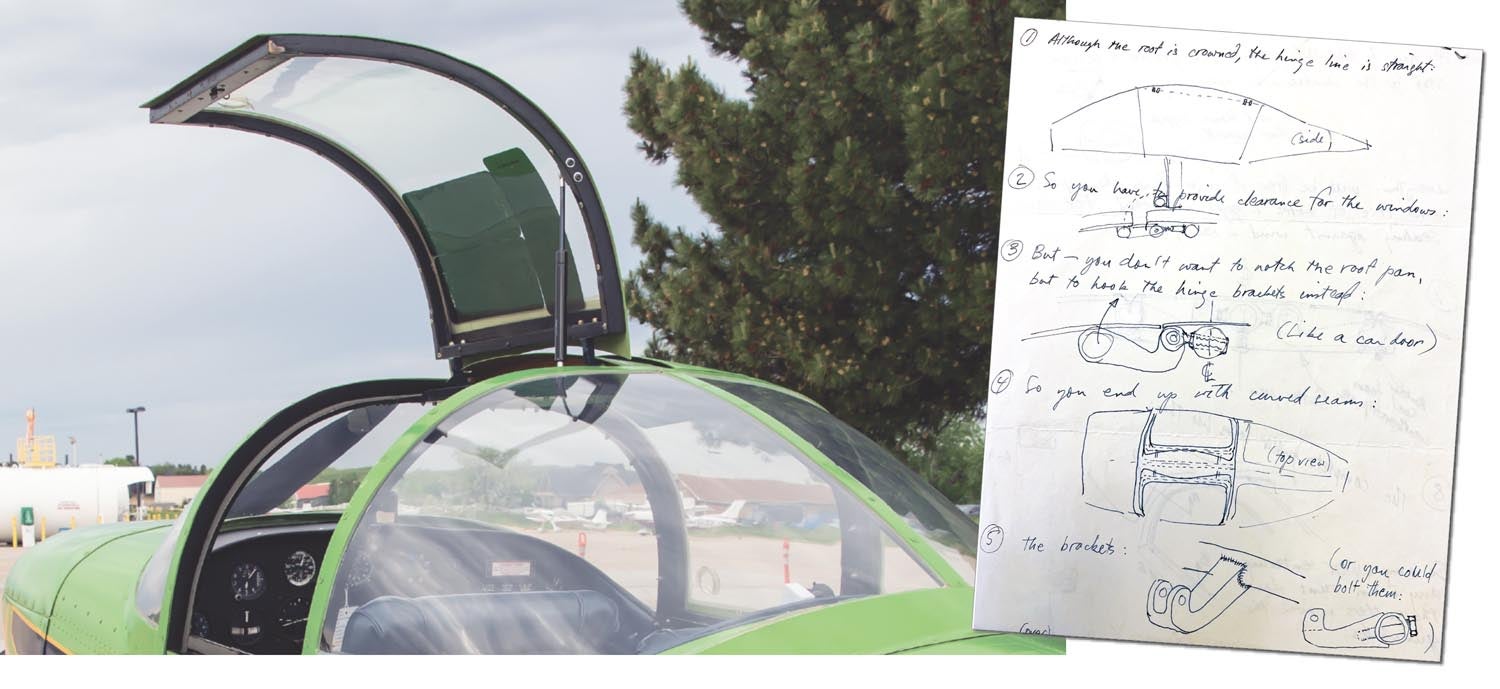

Paired with a fixed-pitch propeller, it has worked well as a good combination for many years. Rather than using the sliding canopy design, Robert went with a gull-wing type door design that was the brainchild of Peter Garrison, who was with FLYING magazine at the time. Peter also designed and built the long-range homebuilt Melmoth. Google it if you’re interested in a fascinating bit of aviation history. It looks rather like the door/window setup one can see on a Glasair. The final covering was with PolyFiber. When the airframe came together, molds were made with plaster of paris for the cowl and windshield, with very nice results. At the finish line, there wasn’t any question as to what color it was going to be painted—after all, what color do you paint an aircraft called an Emerald?

Once done, Robert enjoyed his baby. He describes it as being an “absolute joy to fly” and “the best flying airplane he’s ever flown.” It is responsive and light on the controls, with a tight responsive feel. When asked if he’d change anything, he would have made the rudder/tail feathers straight rather than swept, for the aesthetics, perhaps going with the original landing gear for staying with the spirit of the original design. Otherwise, he wouldn’t change anything. “It’s great on the ground—it is easy to taxi, has great visibility and is docile.” In the air, it’s fun to fly, responsive, yet forgiving. As an airplane it is economical, with enough range and useful load to be practical. It can scratch an aerobatic itch and it’s certainly not spam-can boring. Coming back from the maiden flight, Bob had a moment to talk with his creation. His words: “Damn, airplane, you are just so much fun to fly!”

The New Owners

Time flew by and after a few years, Robert decided on a change and sold it to Ernest “Ernie” Stevens of Colorado. Ernie came from a flying family. His father was an immigrant from Sweden who became an Army Air Corps mechanic during WW-I, working on JN-4 Jennys. He got Ernie involved in model airplanes at a young age, sparking a lifelong passion. During WW-II Ernie couldn’t serve in the military because of health issues but worked at the Boeing factory in Wichita, Kansas, building B-29s. A draftsman, he did the drawings transitioning the bomb bay doors from mechanical to hydraulic actuators. In an ironic twist of fate, he married a woman whose mother was from Hiroshima. The Emeraude has stayed in his family ever since, passed on to his son, Dave, six years ago. Ernie passed away a few years ago, just shy of his 100th birthday.

In one of those “life is weird” things, in 1996 the Emeraude was stolen from a hangar in Colorado. It had been apart for annual, so the thief had to reassemble things as well as re-cowl it, which isn’t easy or a one-person job. That raises more questions than it answers. The Emeraude was flown to the Colorado/Kansas border where the thief tried to land in high winds. He got it down OK, but when he turned to taxi the wind got under the tail and lifted it, causing a prop strike. Ultimately, he wound up stealing the airport courtesy car and was caught in Wichita. It is an unusual aircraft to steal, more so because of the wrenching that needed to be done to get it ready to fly. It raises the question if it was stolen as a specific target—was someone that dedicated to getting an Emeraude? Fortunately, the damage was repaired and it has continued to live a protected and otherwise uneventful life with the Stevens.

Now retired himself, Dave continues to fly the Emeraude frequently. Over the years he’s added a few things. For most of its life the avionics consisted of a handheld radio, which was perfectly adequate. With the fuel tank being in front of the cockpit, the panel itself is only 8 inches deep, making installing anything in that space difficult. However, with the advent of remote radio boxes, he was able to add a panel-mounted radio and transponder and got up to speed with the ADS-B requirements.

So what’s this Emeraude like? As a side-by-side, elliptical-winged sportster stressed for +4.3/-4 Gs, it is more than capable of gentleman’s aerobatics. However, this one, with lap belts only and without inverted oil or fuel systems, rarely goes upside down, and then only positive-G maneuvers. According to Dave, on landing it is predictable. With three notches of flaps available, he normally only uses two. It stalls at 60 mph; he flies the approaches at 90 mph and plans on coming over the fence at 80 mph where it has a very predictable sink rate with enough energy available to arrest it. It cruises at 130 mph. That speed combined with its 26-gallon fuel tank gives it a reasonable range and cross-country performance. Dave plans on comfortable two-hour legs before looking for somewhere to land.

Love & Change

The things we always like to ask pilots in conversations about their aircraft is “what are the three things you love and three things you would change about the aircraft?” Dave loves the Emeraude. In his view, it exceeds his capabilities as a pilot and provides a generous safety margin. It is fun to fly while being forgiving and predictable. Forty-plus years after its first flight, the engine is still tight and doesn’t use much oil. If a genie were to give him three wishes to improve the plane, he’d add a larger fuel tank. Perhaps the CAP 10’s larger rudder to make crosswind takeoff and landings easier, and some days he’d like to switch it back to the original landing gear rather than the Cherokee set for aesthetics.

Years after selling the Emeraude and getting out of flying, Robert Mann decided that it was time to get back in the air. Not one to shy away from another challenging project, he wound up building Emeraude’s big brother, a Beryl. Ask about his second build and his enthusiasm shines through! “Now the Beryl is perfect! I wouldn’t change a thing.” At 82 years old, Robert is still flying his Beryl and loving every minute of it. Robert continues to actively create art out of wood. In fact, in yet another twist of fate, Dave’s nephew Austin flies EA-18G Growlers for the U.S. Navy, and Robert recently made large wooden representations of the squadron crest for a number of the Growler units, including Austin’s. Incidentally, author and photographer Julia Apfelbaum was also part of the Growler community.

Over the years, the Stevens and Robert have stayed in contact and regularly visit. The Emeraude and Beryl have flown together numerous times. We’re hard-pressed to think of a more perfect occasion than these two beautiful aircraft paired, spanning their creation—the beginning of the homebuilt aircraft movement combined with old-school techniques. These are airplanes with outstanding capabilities built on the bones of an earlier generation of aeronautical engineering, crafted by hand while motivated with a love of flight. The technological capabilities of the aviation world have certainly grown by orders of magnitude; however, we’d be remiss if we didn’t look back and tip our hats to what has come before. After all, to quote William Shakespeare, “What’s past is prologue.”

Photos: Julia and Jonathan Apfelbaum.

I knew a cabinet maker from Minnesota who built an Emeraude, I helped him lay out some stripes on it long ago. I heard it initially went to Michigan.

I still wonder about it from time to time. Ron’s had a Franklin Sport Four engine in it. I never knew the N number so I can’t search for it. I consider it another good one that got away!